Struggling against the "Soldiers of Light"

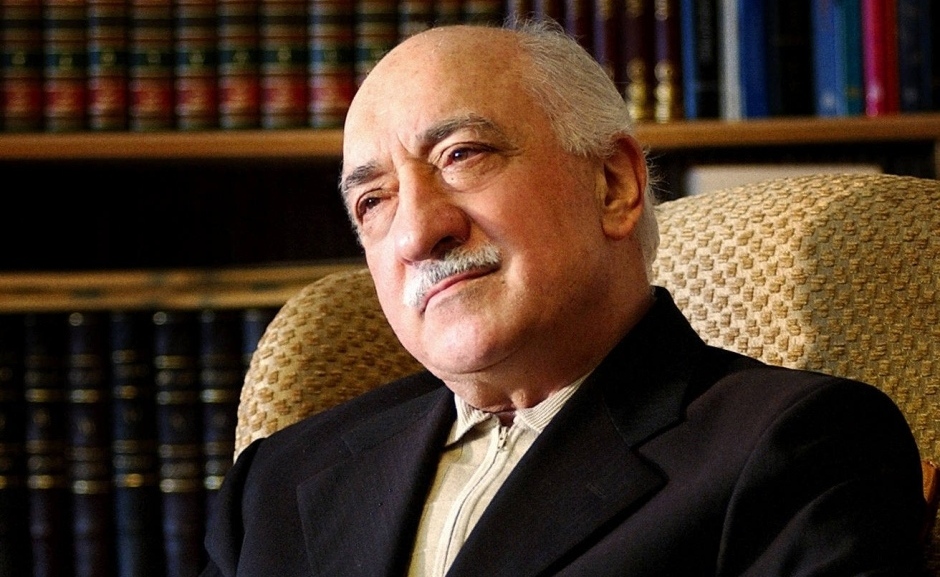

At the time in Erdine, no one was yet aware that the slight Imam from East Anatolia sent to preach in their town by the State Authority for Religious Affairs would become one of the most influential thinkers in the Muslim world. Certainly, the young man who showed up in the provincial Turkish town on the border with Bulgaria and Greece in 1959 was a good, clear speaker.

It was a pleasure to listen to him when he preached in the Mosque about how Islam needed to undergo a process of renewal and that Communism was the core evil of humanity. But how could anyone have predicted that several decades later, Fethullah Gülen would stand at the helm of a powerful movement with several million followers?

Today, the Gülen movement is an ideological concern active on almost all the world's continents. Financed through its own income and donations from wealthy entrepreneurs and benefactors, it runs schools, academies and other educational institutions in numerous countries from the United States to Central Asia, offered via newspapers, television broadcasters, consulting firms and lobby groups.

There are some 300 groups associated with the movement in Germany alone, and two-dozen officially recognized private schools. In Turkey, it has installed its supporters in high-ranking positions within the police and judiciary. Gülen once described his devotees as "soldiers of light" in the battle against darkness. It is a powerful army.

Power struggle within the Islamic elite

But the movement has recently been coming under increasing pressure in, of all places, the nation of its birth. For many years, the "Gülenists" flanked Turkish Prime Minister and his Justice and Development Party (AKP), a party rooted in Islam. Both had a common enemy: The once omnipotent Turkish military.

The primacy of the Turkish army has however in the meantime been broken – and the marriage of convenience between the supporters of Erdogan and the disciples of Gülen has suddenly become mired in mistrust, indeed to some extent open hostility. The "soldiers of light" have turned their backs on Erdogan – just as he has on them. While the media owned by the Gülen movement – the newspaper "Zaman", for example – continue to come out firmly in support of President Abdullah Gül, the AKP's number two, critical reports on Erdogan are stacking up.

The background is a power struggle that has barely attracted any attention abroad, a struggle that on this occasion is not taking place between Kemalists and the new Islamic elite, but within the Islamic elite itself. "The AKP and the Gülen movement testify that a Muslim middle and upper class has been or is being established, that no longer seeks political confrontation with the Kemalist state, but that wants to integrate its supporters into existing state and economic structures and gradually overhaul state and society in this manner," writes the German expert on Turkey Günter Seufert on the subject in a recently published study by the German Institute for International and Security Affairs ("Is Fethullah Gülen's movement overstretching itself? A Turkish religious community as national and international actor").

The AKP and Gülen movement had faith "in the economic dynamic potential within the Muslim-conservative populace. Both have, although to a differing extent, produced their own educational elite," ascertains Seufert, "both share the vision of consolidating the influence of their nation in the region and worldwide." Now that the Islamic allies have won the power struggle against "secularists", "Kemalists", the military and the judiciary of the old ruling class, they are fighting over distribution of the loot.

Erdogan sends in the tax inspectors

Differenzen zwischen

There have been more frequent spats between the Erdoganites and the Gülenites in recent years, although the Gülen camp – and sometimes the man himself - represented for the most part more liberal, "more modern" and "more western" views. The conflict didn't become generally visible until February 2012, when an Istanbul public prosecutor wanted to quiz Turkish intelligence agency head and Erdogan confidant Hakan Fidan on the talks held behind closed doors in Oslo with members of the Kurdish terrorist organization the PKK.

Fidan's agents had conducted these talks at Erdogan's behest, as part of a plan to resolve the Kurdish conflict. But in February 2012, Fidan was accused of "the betrayal of secrets" and "collaboration" with extremists Kurds in the "founding of a Kurdish state". But before Fidan could be arrested, Erdogan intervened. The public prosecutor, generally held to be a supporter of the Gülen movement, was replaced, while Erdogan's spy chief was protected from having to answer to any future accusations from prosecutors with a law hastily approved by parliament.

In future, the head of Turkey's intelligence agency can no longer be summoned by public prosecutors without the consent of the Prime Minister. Erdogan viewed the actions of the public prosecution against his confidant Fidan as a direct political attack on himself – and for its part, the Gülen movement said nothing to convince him otherwise, says Turkish journalist Kadri Gürsel.

Erdogan has in the meantime lashed back in other ways. Tax investigators swooped in on Boydak Holding, a company specializing in furniture production and textile manufacture thought to be one of the biggest donors to the Gülen movement, to carry out an inspection covering several years in one go. The AKP is fond of launching tax raids on companies as a way of making them see sense.

On 13 November this year, "Zaman" (a newspaper belonging to the Gülen group), reported that the AKP's next move was going to be the closure of what are known as Dershanes – tutorial schools offering special preparatory courses for higher education entrance exams. Their function would be taken over by regular state schools in future, said the report.

AKP deputy Orhan Atalay described the private tutorial schools as quasi terrorist "parallel structures" that the state could not tolerate. Atalay did not say what is commonly known in Turkey: That many of these schools are run by Gülen's people. For the movement, not only are the schools an important source of income, they are also a fertile recruiting ground for new supporters. And now, Erdogan's government clearly wants to put to a stop to this.

Questionable impact on local elections

A further detail of the power struggle became known at the end of last month. On 28 November, the Istanbul daily newpaper "Taraf" (not associated with the Gülen movement), published excerpts from the protocol of a meeting of Turkey's National Security Council from August 2004, at which delegates agreed to take action against "reactionary groups", among them the Gülen movement. Such action included the systematic surveillance of supporters and institutions of the Gülen movement in Turkey and abroad. The resolutions were also signed by Erdogan and Abdullah Gül, who was Turkish Foreign Minister at the time.

The authenticity of the protocol published by "Taraf" was unambiguously confirmed by the government: Erdogan and the intelligence service brought an action over the publication of state secrets. What was supposedly the latest salvo in the row came last Tuesday, when some suspected that the arrest of three sons of ministers in Erdogan's cabinet on accusations of corruption was the work of the Gülen movement.

The German political scientist Ekrem Eddy Güzeldere, who lives in Istanbul, attributes the conflict between the Muslim AKP ad the Muslim Gülen movement to the fact that Erdogan now feels strong enough to do without with allies whom he, unlike his party, cannot control. The Gülen movement may be represented in ministries, and has not least become so strong within the police and judiciary because the AKP intermittently promoted it. "Now that they have stabilized their power, the AKP and Erdogan perceive it to be increasingly less essential to have partners and forge alliances. They want to govern alone," says Güzeldere.

What is questionable however is whether the fracture between Turkey's two most powerful Muslim reformers will impact upon local elections scheduled for March next year. After all, it is unlikely that Gülen supporters, most of whom have thus far voted for the AKP, will transfer their support en masse to the opposition Republican People's Party or the party of the nationalist movement. These parties, rooted in Kemalism, do not stand for the Turkey of devout but highly educated Muslims that the Gülen movement tries to attract.

It is more probable that many Gülen supporters will switch to Turkey's growing camp of non-voters or that they will back independent candidates. Voters who listen to Gülen's electoral recommendations, according to Turkish opinion polls at most six or seven percent of the Turkish electorate, could reduce Erdogan's share of the vote in March as a consequence of the fissure between the governing party and the nation's most important Islamic movement, but this will not represent any short-term threat to his power.

However, it would not be a good omen for the AKP to have the Gülen movement against them in the long-term. Supporters of the movement are educationally above-average and optimally networked. Its educational offensives have achieved much that is positive. But like any ideologically-oriented association the Gülen movement harbours the risky desire for growth, and therefore for power. That's something the Gülen movement continues to have in common with Erdogan and the AKP.

Michael Martens

© Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 2013

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de