New freedoms, old prohibitions

Hassan Rouhani, Iran's president, recently said something that triggered a wave of protests from the country's conservatives. He said: "Don't interfere in people's lives so much; leave them to choose the road to paradise for themselves. You cannot lead people to paradise by force and with whips."

His words hit a nerve. In the Islamic Republic, the fear of a cultural infiltration or, as it's officially called, a "velvet culture war", is much greater than the fear of sanctions or a potential military intervention. This "war" is usually portrayed as a conspiracy by the West, the aim of which is to bring about regime change in Iran. The reality, however, is that the cultural disputes to which it refers are actually a battle between tradition and modernity, a struggle between two camps on either side of a divide that runs across the entire Islamic world and is growing ever fiercer.

In some countries, such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria or Iraq, the fighting has been bloody; in other states, such as Turkey or Iran it has not yet, with a few exceptions, gone beyond the boundaries of the political. It seems certain that the whole of the Middle East and large parts of Africa will be shaped by this ideological battle in the coming years.

Ever since it was founded, the Islamic Republic of Iran has sought to Islamise the whole of society, cleansing it of the "decadent" culture and civilisation of the West. However, right from the outset, various factions within the Islamic camp have vied with each other not only for power, but over the implementation of their differing concepts of an Islamic state.

For many years, these arguments were internal and took place behind closed doors. It was only when Mohammed Khatami became president in 1997 that the differences of opinion within the system – some of which were considerable – surfaced for all to see. While the conservatives were striving for a pure Islamic state, the reformers under Khatami demanded the implementation of the republican elements enshrined in the constitution.

Rouhani's vision of a more open Iranian society

President Khatami's plans foundered as a result of vehement opposition from the conservatives, who monopolised power for themselves for eight years with President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad at their head. Since Hassan Rouhani was elected president just over a year ago, the battle has been ignited once again.

During his election campaign, Rouhani promised liberalisation and increasing openness, both towards the outside world and within the country itself, which was to include the relaxation of Iran's stringent censorship, meaning more freedom for the press, art and literature, the removal of checkpoints on the roads, and the moderation of the country's strict religiously-grounded prohibitions.

"We are not leading anyone to paradise by force, but we want God's rules to be obeyed," said the influential conservative cleric Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami in response to Rouhani's statement. "You recommend that we leave the people to their own devices and not lead them to paradise by force. Very well. Let's suspend all prohibitions and commandments and just tell Mr Criminal and Miss Immodestly Dressed Girl to be good. Is that Islamic or the concern for seeing God's laws obeyed? We have to defend our political order and counsel everyone not to tread the path to hell."

The preacher pilloried all art and culture, which, in his view, has been influenced by the West. He branded music "an offence against God and culture," stressing "We aim to achieve a religious culture." Culture, he said, must serve to help young people in their search for their own identity – an identity they could only form within the framework of religion, adding that foreign channels broadcasting to Iran were spreading "decadence and emptiness".

The road to paradise

Ahmad Khatami called on the government to take steps to combat "Western influence". "The spiritual and cultural viruses" spread by foreign broadcasters were "worse than the plague," he said, adding that the Islamic Republic was duty-bound to lead the people to paradise. "We cannot just leave the people to do whatever they like, morally, economically and culturally."

Alam al-Hoda, a preacher in Mashhad, went even further in speaking out against President Rouhani. He said quite bluntly: "We won't just use whips; with all our might, we will resist those who wish to block the road to paradise."

But how do the conservatives plan to bring Iran out of its economic crisis and protect the country from social unrest without making at least some concessions to the West? If there are no reforms, the USA may well stick to its policy of economic sanctions. But the ultra-conservatives would seemingly prefer to subject the population to further economic privations than lose their ideological footing in the population.

"If our concerns were of a purely economic and material nature, we would not have needed to have a revolution in 1979," says the cleric Mesbah Yazdi. His idea of Islam is socially all-encompassing; it consists not only of prayers and fasting. The website of the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution is more specific: "The Council's aim is to create a model for the development of society in which society progresses from its current state to an ideal state. This means a conscious change in the opinions, feelings, values and convictions of society as a whole."

The Internet as an opportunity

The power of the conservatives in Iran is rooted in the country's institutions, many of which are in their hands. This allows them to constantly lay obstacles in the path of the moderates around Rouhani and to torpedo their decisions.

This leads to absurd situations. Take, for example, the use of social networking sites: even though it is forbidden to use Facebook and Twitter in Iran, the president, foreign minister and numerous members of the cabinet are some of the country's most enthusiastic users of the digital forums. What is more, Rouhani is urging the population to use social networks as often as possible. The age of dictatorship, with announcements delivered via loudspeaker or from the pulpit, is over, he says. "We have to look on the Internet as an opportunity to display our Iranian and Islamic culture."

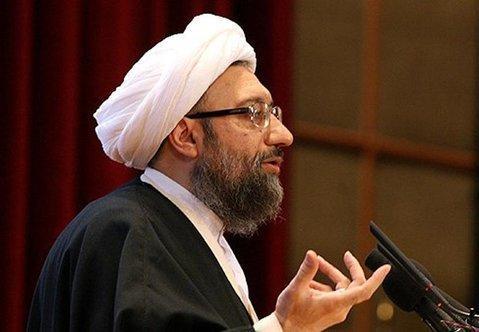

To this, Sadeq Larijani, head of the Iranian judiciary, responds: "Anyone who overlooks its poisonous atmosphere would seem to have no idea about the Internet." He has compared the Internet to a "swamp" that should be "surrounded with barbed wire". But to his chagrin, millions of Internet users in Iran have found ways to get over the justice department's fences.

Another absurdity is the fact that a large proportion of the Iranian population receives foreign Persian-language television and radio programmes even though the satellite dishes needed to do so are prohibited. The security services continue to confiscate the dishes, but that doesn't stop people from installing new ones as soon as the inspectors have gone. According to Culture Minister Ali Jannati, four million Iranians communicate via Facebook and 71 per cent of the inhabitants of Teheran use satellite dishes.

"This means that millions of people are acting illegally every day," the minister said. His government is resolved to lift the restrictions. "We cannot shut ourselves off from the outside world. We cannot prohibit everything under the pretext of protecting moral values."

Relaxing censorship

Overcoming the censorship of books, films, art, music and of course the press is a more difficult task than overcoming censorship on the Internet. Hundreds of books have been blocked by the censors for years, without any reasons being given. Rouhani has said: "We must work to ensure that opinions and thoughts can be expressed freely." He went on to say that this is not possible without freedom. His government's aim, he said, is the abolition of censorship. His culture minister, Ali Jannati, in whose ministry the censorship authority is housed, has said that culture can only develop in an atmosphere of openness and diverse opinions.

Nevertheless, neither the censors nor the Justice Department are allowing themselves to be swayed by the words of the president or the culture minister. A whole series of journalists, authors, publishers, film makers and artists are in prison; many of them have also been banned from their professions.

A year after coming to power, Rouhani's government has achieved very little by way of a domestic opening in Iran. The Tehran Symphony Orchestra's performance after a hiatus of many years and the re-opening of the "House of Cinema", the guild of Iranian filmmakers, are two of the few steps worth mentioning.

That being said, the verbal statements about freedom and diversity alone have caused a tangible change in the atmosphere within the country and have awakened new hopes. A success in foreign policy, particularly in the ongoing nuclear negotiations, could well give the government the moral support it needs to prevail against the conservatives.

Bahman Nirumand

© Die Tageszeitung/Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de

Bahman Nirumand is a journalist. Born in Tehran in 1936, he was active in the 1968 student movement and experienced the 1979 Iranian Revolution first-hand.