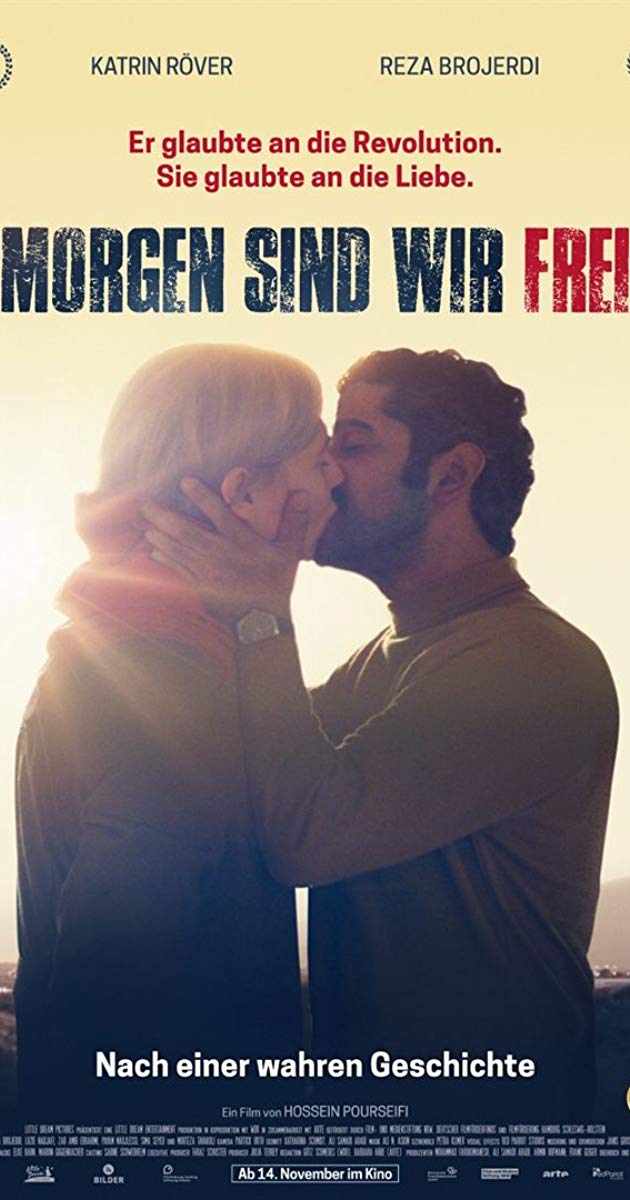

Love in the time of revolution

"Morgen sind wir frei" tells of an Iranian-German family in the GDR who decided to emigrate to Iran shortly before the Islamic revolution in 1979. The 44-year-old Omid (Reza Brojerdi) is a communist who follows the fall of the Shah Mohammad-Reza Pahlavi from afar with great fervour. His wife Beate (Katrin Rover) – a 37-year-old chemist – observes developments in Iran with a blend of joy and concern at the thought of living in a foreign country. Meanwhile their young daughter Sarah (Luzie Nadjafi) diligently learns the Persian language.

Shortly after the fall of Pahlavi dynasty, Omid travels alone to Iran to make sure that everything is in order in his country of origin; a few months later Beate and Sarah make the journey. This marks the beginning of a rocky, irreversible phase in the life of the young family.

More than the history of a revolution

Omid and Beate captivate the audience right from the start. The couple's loving co-existence is more than a dry narrative, more than a vignette of the Iranian revolution.

One recurring symbol in the film is the face of a man, black and white graffiti on the house wall opposite the family's living room. The man observes the family with a piercing gaze. In various sections of the film, viewers can also hear his voice: "if we had acted as revolutionaries from the beginning, if we had silenced the press, if we had banned the corrupt parties and brought their leaders to justice, if we had set up gallows in the main squares, we could have saved ourselves all the trouble". It is the voice of revolutionary leader and founder of the Islamic Republic: Ayatollah Khomeini.

"The film is based on a true event. I met this family eleven years ago. She used to live in Leipzig. When I heard her story, I decided to film it," says screenwriter and director Hossein Pourseifi, who himself has lived in Germany since he was nine.

Many archive pictures from the time of the revolution have been incorporated into the film. The family house in Tehran has a beautiful courtyard. The pictures outside the house are shot as true to the original as if the camera had actually been on the road in the Iranian capital.

"The film was shot near Cologne, Bonn and Leverkusen. The house is also located in the region. The interior was recreated with matching accessories and decorations. We shot the courtyard and some scenes outside the house in Spain. The houses and the city that the audience see through the window were made from older pictures and video material with the help of computer technology," explains the director.

Just one example

"Morgen sind wir frei" describes the collective fate of many families during the first decade after the revolution, a revolution that gradually consumes their children. The lives of Omid, Beate and Sarah are very quickly turned upside down by the profound developments that are changing society as a whole: the forced veiling of women, the aggression against political opponents, the ban on newspapers and many political groups, the Cultural Revolution and its consequences for universities, lecturers and students, the 1981 executions and the mass executions in 1988.

The scenes are symbolic and short, but effective. "In a 97-minute film, one cannot show all the events of the revolution. We have therefore decided on the developments that shaped the fate of this family. For example, the introduction of Islamic dress codes for women is shown because it has an effect on the life of the family. We omitted other events because they had nothing to do with the history of the family," says director Pourseifi. "The two producers of the film, Mohammad Farokhmanesh and Ali Samadi Ahadi, lived through the period. So during the montage we decided to run thematically fitting excerpts from Khomeini's speeches in the background," says Pourseifi about the scenes in which the original sounds of the revolutionary leader can be heard.

"Over the past forty years, the Islamic Republic has invested huge amounts of energy and resources in producing films and series about the revolution that reflect its perspective. We have tried with the means at our disposal to present the revolution from the outside," says the director and screenwriter.

An indictment against the regime and the opposition?

At the same time, the film views the Iranian revolution from the perspective of the German media. Reporters can be heard depicting and commenting on the events in Iran. They are also original. "I spent hours searching the WDR archives for original material. Every report is authentic. For me it was interesting that much of what the reporters had predicted at the time about the future of the revolution later turned out to be true," says Pourseifi.

"Morgen sind wir frei" not only shows the aggression of the rulers and their disregard for democracy. It also pillories the politics of the left-wing opposition, which supported the Khomeini regime immediately following the revolution in the name of "fighting imperialism" and was later fought and crushed like other political groups.

The script reflects the themes of that time well. Are civil liberties, women's rights and the fight against Islamic dress codes more important, or the fight against imperialism, the interests of the party and absolute submission to its central committee? This decision confronts Omid's small family with new challenges every day.

Every evening, little Sarah reads the Koran with her religious grandmother. Beate and Omid's niece (Tsar Amir Ebrahimi) - a young student - tries to make Omid understand that it is not "paradise" he is fighting for. Beate tries to protect her husband, daughter and life from the violent waves of politics and religion.

Every day the contradictions become clearer to Omid. He is in a dilemma. The colourful headscarf, which slightly covers Beate's smooth hair at the beginning of the film, gradually turns into a large dark scarf that obscures her face. The film exposes the double standards, deceptions and forced lies in a single sentence, as Omid says to his daughter: "If you are asked about your religion at school, say that you are a Christian".

For those who witnessed the reprisals of the first decade after the revolution in Iran, the way the atmosphere is depicted is by and large credible. Occasionally those in the know may need to turn a blind eye - no feature film can be in absolute harmony with reality. In one instance, however, the criticism is justified: an employee appears in the office of a university lecturer (Enissa Amani) heavily made-up, with operated lips and cheeks. This may be the image people have acquired of Iranian women in recent years, but the generation prior to the revolution had a completely different picture in their minds of working women.

Maryam Ansari

© Deutsche Welle/Iran Journal7Qantara.de 2019