Diary entries from the darkness

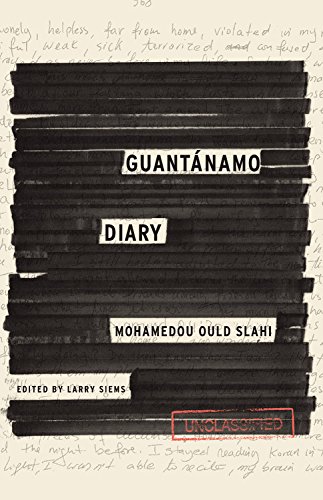

Reading Mohamedou Ould Slahi's "Guantanamo Diary", you quickly realise that this is not a normal book. Many of the words, sentences and pages have been redacted with thick, black bars. They fell victim to the US censor. But censorship is only one part of this system, and the greatest victims are not words, but people. Mohamedou Ould Slahi is one of them – one of many.

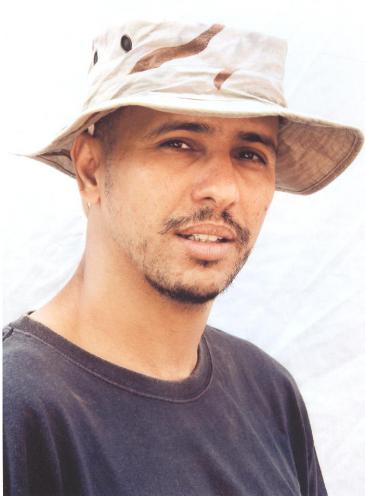

The Mauritanian's martyrdom began in the year 2000 when Slahi, who had at one time fought alongside the CIA and the Afghani mujahideen against the Soviet puppet government in Afghanistan, was arrested for the first time by the Mauritanian authorities. They kept saying he was involved in this or that activity, or had been seen with one person or another. However, there was never any concrete evidence.

Both Germany, where Slahi had been a student, and Canada, where he had worked for a while, gave him a clean record. But under pressure from the USA, the Mauritanian secret police had to keep interrogating him. It became routine for Slahi, and he remained on friendly terms with most of the officials. There was a mutual respect between them. He knew their troubles and their family histories, and they all knew that Slahi couldn't have been more innocent. He did not think for a second that he would one day be extradited.

But things changed suddenly in 2001: just a few weeks after the 9/11 attacks, Slahi was extradited to Jordan. The Jordanian regime is one of the USA's closest allies in the "war on terror" and is particularly well known for its torture methods. Slahi had to endure several months there in a high-security wing. But the Jordanians couldn't prove anything against him either.

Then he was sent to the Bagram airbase in Afghanistan, his last stop before Guantanamo. By all accounts, the prison camp on Cuba is paradise compared to the prison at the Bagram US airbase. It was only at the end of last year – shortly after the release of the CIA torture report – that responsibility for this prison was completely handed back to the Afghans. In Bagram, Slahi observed elderly Afghans being detained, harassed and tortured on the basis of the most ridiculous conjectures and suspicions.

Lesson in "American sex"

When Slahi first arrived in Guantanamo, he didn't know where he was. After all the darkness in the jails of Amman and Bagram, he was glad to see the sun, even if it meant he was being beaten outside. The lack of light and sunshine and freedom comes up repeatedly in Slahi's book, which he wrote entirely by hand in his cell.

There, he also learned the English language, which he did not speak well when he arrived. The fact that Slahi is still – even as you are reading his words – being held in this cell is an oppressive thought that is always at the back of your mind.

We have known about most of the torture practices in Guantanamo for some time now. Nevertheless, they appear more horrifying from a first-hand perspective. Female guards who abuse and rape Slahi, teaching him a lesson in "American sex"; constant sleep deprivation; countless punches and kicks; preventing him from praying, and numerous other cruelties once again illustrate the everyday injustice in the prison camp.

Even in light of all these circumstances, Slahi does not forget that his tormentors – however cruel they may be – are still human beings. And so he doesn't only report on patriotic extremist guards, who dismiss his prayers as an "insult to their nation", but also on those who cried when they left the camp and assured him of their friendship. "You men are my brothers", said another. And when a female medical orderly confessed her love to a prisoner and he began to stutter, even Slahi had to laugh.

These impressions make Slahi's point of view stand out from many others – in particular the autobiographical reports of US soldiers, who often see Iraqis or Afghans as nothing more than evil, wild barbarians, and as a result completely dehumanise them.

Stopped from reading his own book

"I think that the book has a very strong influence. Now people know how it feels to be the victim of unlawful imprisonment, subjected to constant torture", says Nancy Hollander, Slahi's lawyer. Hollander herself is not even sure whether her client knows that the book has now made it onto the "New York Times" bestseller list.

Last February Linda Moreno, another lawyer and the woman behind publication of this book, visited Slahi and told him about his book's success. Prior to publication, Moreno had not been able to get in touch with the prisoner even once to discuss the manuscript and any potential corrections or changes. She therefore simply acted to the best of her knowledge and according to her conscience, a point she emphasises in the foreword.

Moreno was also intending to bring Slahi a copy of his bestseller, but the authorities in Guantanamo prevented it. According to the regulations there, Slahi was not allowed to read his own book. The absurd reason for this was that he may have been the author, but the introduction and the footnotes had not been written by him. These could – so the authorities claimed – contain "classified information". Almost all the books in Slahi's possession have now been confiscated again. The only book he has been permitted to keep is the Koran.

Moreno's visit provided Slahi with his very first opportunity to explain his view of things since the book's publication. But she is not allowed to publish what he said. Here too, the system has exerted its powers of censorship, classifying his statements as "secret" and preventing publication – for now, at least.

Slahi learned English, the "language of the enemy", behind bars. But he is truly a born storyteller. In spite of the torment and torture he has been subjected to, he always endeavours to remain fair. Readers will be taken aback by the fact that he has retained his sharp sense of humour, even after all the injustice he has experienced. But Slahi's diary is not finished. At some point – when Slahi finally obtains justice – a complete version will be published. Unredacted. Uncensored. And written in freedom.

Emran Feroz

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin