Pakistan's "Commission for Minorities" without the Ahmadis

"Naya Pakistan", or new Pakistan was Imran Khan’s 2018 election campaign slogan. As he indicated over and over at the time, he intended to liberate the nation from the corrupt elites and political family clans that had been sucking Pakistan dry like leeches for decades.

The populist electoral pledges for greater justice, tolerance and improved participation stirred the hopes of young voters in particular. In late 2018, Khan won the elections and became prime minister, admittedly with a little help from the powerful "establishment", the military.

Following his induction, he once again declared his intention to doggedly continue the fight against corruption and extremism in society. After almost two years in power, there is little evidence of the promised changes. Recently Khan’s close associates have been embroiled in corruption scandals and Pakistani society is still as intolerant as ever.

"National Commission for Minorities"

The example of the National Commission for Minorities is just one glaring example. In 2014, following a wave of attacks on religious minorities, the constitutional court instructed the government to set up a National Commission for Minorities. The commission’s role is to monitor compliance with the constitutional rights of minorities and advise the cabinet on issues concerning those minorities.

The government recently tasked the Ministry of Religious Affairs with the job of setting up a forum along similar lines, whereupon the Minister for Religious Affairs presented the cabinet with a panel with representatives of all religious minorities – apart from Ahmadi Muslims.

When several cabinet members voiced their displeasure at this omission and demanded that the Ahmadis be assigned representation on the panel, it triggered fierce controversy. Islamist parties, politicians, scholars, government ministers and members of the public unleashed their anger and hatred over the participation of "qadianis" – a pejorative term for Ahmadis – in a government body.

Calls for murder and boycotts circulated on social media and the hashtags "qadianis the world’s worst infidels" and "qadianis the worst traitors" were trending for several days. In a television interview a few days later, the Minister for Religious Affairs Noor-ul-Haq Qadri said: "Anyone showing sympathy or compassion for qadianis cannot be loyal to Islam and Pakistan."

Khan’s government caved in under the pressure and categorically ruled out any Ahmadi participation in the commission, remarking that the Ahmadiyya question was a "religiously and historically sensitive" matter. This could have been predicted. Imran Khan took his first U-turn in late 2018 shortly after his inauguration. He had appointed a number of renowned experts to his Economic Advisory Council (EAC), among them the world-famous economist and Princeton University professor Atif Mian, an Ahmadi. The IMF ranks Atif Mian among the world’s top 25 economists. The news of Mian’s appointment soon attracted the attention of religious hardliners who demanded his immediate removal. Khan bowed to pressure at the time and forced the economist to stand down from the EAC.

Obsession with religious affiliation

Pakistan’s conduct towards the Ahmadis and its obsession with religious identity is symptomatic of the radicalisation of society that permeates all areas of life and is reflected in the laws of the land.

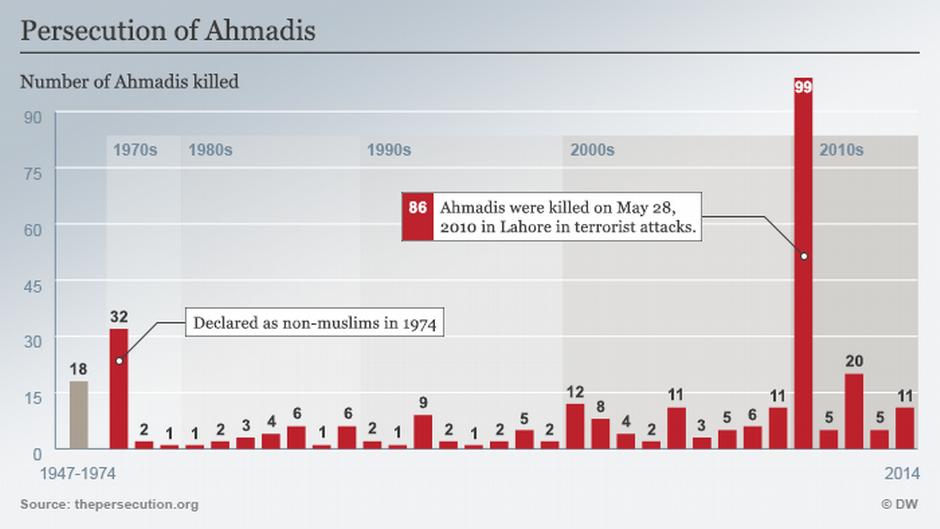

The Ahmadis were declared a non-Muslim minority in 1974, because they regarded their founder Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad as the long-awaited Messiah and as an ummati nabi, a prophet within Islam. Since 1984, practically all the religious activities of this community have been criminalised, not only by notorious blasphemy laws, but also by what is known as the anti-Ahmadiyya Ordinance XX.

For example in criminal proceedings, they are not allowed to call themselves Muslims, describe their mosques as mosques or "to pose as a Muslim" – behave like a Muslim, whatever that is supposed to mean. Therefore, for example, the simple greeting "Assalamu alaikum" (peace be with you) can constitute an infringement. And indeed, Ahmadis have ended up in prison for this "offence".

Despite repeated criticism from the United Nations, HRW, Amnesty International and other human rights organisations, this mediaeval jurisdiction remains in force. Criticism of the legislation can have fatal consequences, as in the case of Salman Taseer, the governor of Punjab. Taseer had spoken out in defence of Asia Bibi, the Christian woman accused of blasphemy and described blasphemy laws as "kala qanoon" , or "black law". He was shot dead by his own bodyguard in broad daylight. Taseer’s murderer, who has since been hanged, is revered like a saint by a large section of the populace.

The ostracised minority

The Ahmadis are among the most persecuted and ostracised minority in the south Asian nation. In Pakistan, it is easy to put pressure on political opponents and rivals by accusing them of being "qadiani nawaaz", pro-qadiani or worse still, a qadiani themselves. This is all it takes to put the accused on the defensive and force them to evince their "correct" faith as an absolute priority. Even the powerful army chief Bajwa was not spared this treatment. Many shops and bazaars publicly display posters with the words "Qadianis keep out" or "Qadianis should first enter Islam, and then my shop". There are warnings against "qadiani" products such as the popular Shezan mango juice, as though mango juices also follow a religion.

Daily calls issued by scholars such as "qadiani wajib ul qatal hen" (the Qadianis must be punished by death) pass by without any legal action. When in the year 2010, after two devastating terror attacks on Ahmadi mosques with more than 80 deaths, the prime minister at the time Nawaz Sharif addressed the marginalised minority as "our brethren", he was lambasted by the mullahs, who said that "qadianias" could never be the brethren of Muslims. A judge at the Supreme Court in Islamabad recently demanded that Ahmadis should add the suffix "qadiani" or "mirzai" to their names to make them more easily identifiable. In Pakistan, you don’t get more outcast than this.

Meanwhile, the blatant smear campaign continues across social media, with all manner of politicians and scholars talking about the minority in endless television talk shows. But we never hear from the Ahmadi Muslims themselves. No mainstream television channel or newspaper ever asks them for their point of view. And in any case, Ahmadi publications have been officially banned for years. Any discussion on an equal footing is impossible and as a consequence, the discourse is dominated by the unilateral anti-Ahmadiyya narrative.

The Ahmadis are nothing but spectators in a drama in which they have already been accused, convicted and punished, without anyone ever listening to their side of the story.

Mohammad Luqman

© Qantara.de 2020

Translated from the German by Nina Coon