The dance goes on

The dhamal, the ecstatic whirling dance of Pakistani Sufis, is one of the most vibrant and colourful manifestations of Muslim spirituality. When the long-haired dervishes of the subcontinent revolve into transcendence to the rapid beat of the drum, the individual vanishes for a moment. Many Sufis describe this experience of unity as the climax in their striving to reach God.

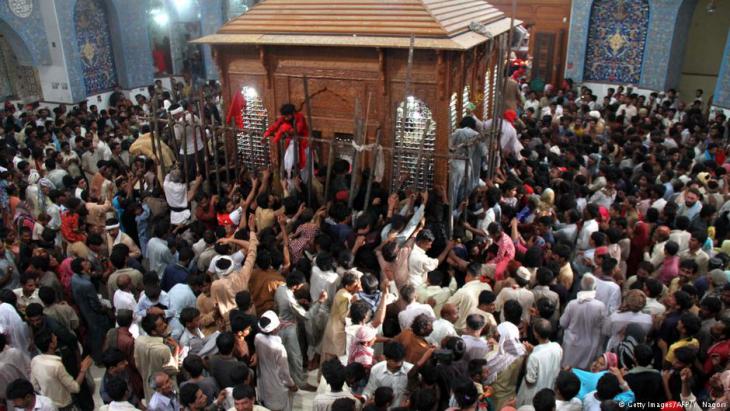

When on Thursday, 16 February, an IS suicide attacker killed 88 people at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in the Pakistani city of Sehwan, hundreds of pilgrims were gathered there for the evening dhamal ritual. The Sufi shrine in Sindh province is known far and wide as "Sehwan Sharif".

The figure of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, a 12th century scholar and poet, plays an important role in the identity of the south Asian Sufis. Following his death, the mystic was identified by the Hindus in Sindh with the deity "Jhule Lal", whose epithet he carries to this day. In the repertoire of the qawwali singers there are several songs about Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, of which "Dama Dam Mast Qalandar" has become a kind of universal Sufi hymn.

Lal Shahbaz Qalandar – symbol of Pakistan's religious pluralism

In Pakistan's unabating series of terror attacks, Sufi shrines are a recurrent target. The attack on the shrine of Data Ganj Bakhsh in the heart of Lahore, which killed more than 40 people in 2010, was especially traumatic for Pakistani Sufis. In the years that followed, attacks were carried out against Sufis in all parts of the country, most recently last November at the shrine of Shah Nurani in the western province of Baluchistan.

Like no other shrine in Pakistan, the shrine in Sehwan is a symbol of the religious pluralism that is firmly rooted in this nation. Religious minorities are not only welcome at the tomb of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar – to this day, one of the guards continuing the family tradition of looking after the shrine is a Hindu. Not only that: women dance alongside men in the dhamal ritual. In the forecourt of the shrine, the otherwise ubiquitous separation of the sexes is repealed. This is why on 16 February, a large number of victims were women and children.

The German anthropologist Jurgen Wasim Frembgen, who recently published the travel reportage collection "Sufi Tonic", has travelled to Sehwan many times to attend the Shahbaz Qalandar death anniversary celebrations. Frembgen has spent years researching the folk traditions of the Pakistani Sufis. Sehwan had an aura that made it a very special place for Frembgen in his work. "Popular, informal Sufism is crystallised in Sehwan Sharif and associated with the vibrant dimensions of an active popular Islam," says Frembgen. "What the visitor experiences there is pure emotionality and joie de vivre."

An experience-based religiosity

It is this approach to life that terror attacks against the Sufis in Pakistan aim to destroy. In the everyday lives of most Pakistanis, which are thoroughly regulated by social codes, the shrine visit is a spatially and temporally limited experience of freedom and lightness. Active popular Islam corresponds to the inherently human desire for ecstatic experience – it is rooted in the Islamic tradition, but also goes beyond this in its striving for transcendence. This experience-based religiosity stands in opposition to a sober, literal reading of Islam, which wants to limit religious practice to a series of prescribed rituals.

The ultra-orthodox reading of Islam is a new phenomenon on the Indo-Pakistani continent, one that has little to do with how religion has actually been observed over the centuries. Since the 1970s, the Saudi lobby nurtured by oil wealth has exerted a consistent influence on the religious landscape of Muslims in Pakistan and India. Under the regime of General Zia ul-Haq, Saudi Arabia established a wide network of madrassas in Pakistan, which spreads wahhabi ideas to this day.

Over the course of two generations infected with the foreign body of a blinkered interpretation of Islam, the attitude of many Muslims in Pakistan has changed. Sufis are increasingly labelled as "un-Islamic", shrines branded as heretic places. Dance, music as well as the participation of women and the followers of other faiths are declared to be the practices of "infidels". Contemporary IS terror finds it easier to find legitimisation on this fertile ground of intolerance.

The British historian William Dalrymple compares this development with that of Europe on the eve of the Reformation: in the 16th century, reformers and purists denounced music, paintings, festivals and the veneration of saints as the superstitions of the uneducated proletariat and instead propagated a literal reading of religion.

Sufi traditions will survive

But even though the number of pilgrims attending Sufi shrines has declined slightly in recent years - Forscher Frembgen does not believe that Sufi traditions in Pakistan will die out: "In my eyes, popular Sufi tradition and the folk Islam associated with it represent an Islam that doesn't have a lobby, but it will continue to thrive, because it does the most to meet the needs and desires of those living in poor rural areas and city slums," he says.

For many Sufis in Pakistan, the chaotic present with its excessive violence has something of a vale of tears quality. As most Sufi pilgrims are pursuing a personal spiritual quest or continuing long-held family traditions, they do not allow themselves to be deterred by violence. For Frembgen's work, the heightened risk means avoiding gatherings of people at the large shrines. But it is nevertheless important to him to highlight the cultural wealth of Pakistani folk Islam – especially now.

"I'm trying to champion a folk Islam that is still contemptuously described as 'superstition' by Islamic theologians," says the anthropologist.

It is astonishing how relatively little coverage the international media devoted to the Sehwan attack. It is easily forgotten here that the most serious IS threat is faced by moderate Muslims in nations such as Pakistan. At any rate, at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, people issued a clear signal to the IS bombers: just a few hours after the attack, custodians of the shrine allowed the dhamal to continue. The dance goes on.

Marian Brehmer

© Qantara.de 2017

Translated from the German by Nina Coon