Afghanistan's repressed Hazaras face a hostile Taliban

As Taliban fighters patrolled Kabul's streets, a terrified 19-year old – hidden away at home like countless other women and girls – turned to her beloved movies for solace. Her current favourite, she said, was "V for Vendetta": set in a dystopian future, it features a lone freedom fighter, plotting to overthrow an all-powerful, Orwellian tyranny.

But instead of offering comfort, hope even, the movie just made her feel more depressed, she said, as she painfully recalled how different her life had been when she last watched it: then she was a final-year high-school student, who planned to study photography at university.

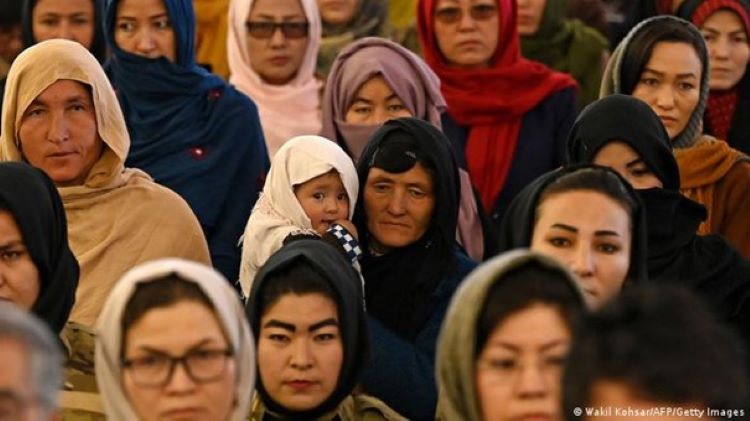

Historically targeted by the Taliban

When we spoke to her, she had not left her house in two weeks, ever since the Taliban swept into Kabul. She was wracked by anxiety – and despair. Her life, she said, her voice breaking, was "ruined."

Born in 2001, the year the Taliban regime fell, she had heard relatives speak of their brutal rule, characterised by public executions, widespread hunger, a ban on music and education for girls. And, above all, they had told her terrifying tales of massacres, forced conversions and persecution of Hazaras.

Her family belongs to this ethnic group, made up of predominately Shia Muslims, that accounts for up to 20% of the country's population. Hazaras have been discriminated against for decades. Their distinct features make them easy prey for Sunni hardliners, both Taliban and Islamic State (IS), who consider them infidels.

Following the fall of the Taliban, their situation improved. Some Hazaras rose to prominent positions in politics and society, including the office of vice president. The period also saw a flourishing of Hazara civil society and advances in education, despite entrenched discrimination and several terror attacks, including one on a maternity hospital in Kabul last year. So far, no group has claimed responsibility for the attack, although many foreign governments point to IS perpetrators.

"In mortal danger"

To assuage fears of a return to their brutal rule, the Taliban have put on a show of moderation. Spokesmen have repeatedly vowed to refrain from retributions and to respect the rights of women and minorities.

They even made a point of sending representatives across the country to secure Afghanistan's Ashura processions last month. The annual mourning ritual is undertaken by Shias every year to commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. Hard-line Sunni groups view the practice as heresy.

Many Hazaras believe the group's self-professed inclusiveness is little more than propaganda aimed at the international community, whose development aid is a lifeline to prop up an economy teetering on the edge of collapse.

None of the Hazara men and women still in Afghanistan that we spoke to believed the assurances. Mahdi Raskih, a Hazara parliamentarian until the Taliban captured the capital, said that Hazaras face "ethnic and religious persecution" by the militant group. They were, he added, "in mortal danger."

Massacres and a harrowing message

Amnesty International's latest findings seem to prove their worst fears. On-the-ground researchers documented brutal killings of nine Hazara men in Ghazni province in central Afghanistan, which took place in early July. Six of the men, according to the report, were shot; three were tortured to death by Taliban fighters.

The killings, Amnesty's report goes on to say, likely represent "a tiny fraction of the total death toll inflicted by the Taliban to date", as the group had cut mobile phone service in many of the recently captured areas, effectively controlling which photographs and videos are then shared from these regions. Eyewitnesses who capture images on their phones are often too scared to keep them, lest they be found with evidence.

Habiba Sarabi, a Hazara political leader, admitted she had proof of more atrocities, but could not share the details, as it might endanger surviving eyewitnesses. Sarabi was the first female governor of Afghanistan and one of four women representing Afghanistan in the negotiations with the Taliban in Doha. When we spoke to her, she was still reeling from the Taliban's takeover. She was, she said, "in shock."

Soon after the interview, Sarabi sent a link to a short, grainy video, which showed two Taliban fighters. Speaking into the camera, one of them says they are waiting for permission from their leaders to "eliminate" all Hazaras living in Afghanistan. While we were unable to verify the video, it has nevertheless been shared widely among Hazaras to whom it sends a chilling message.

"I'm numb," said one Hazara after watching it. It had taken her breath away, she said.

The looming resurgence of Islamic State-Khorasan (ISI-K) following the withdrawal of U.S. forces and de facto collapse of the Afghan army represents yet another threat. Many fear that once the attention of the international community and media has shifted elsewhere, the Taliban will start a campaign against those who might lead a Hazara resistance.

One of them is Zulfiqar Omid, a former lawmaker turned resistance leader. He revealed he has established an armed Hazara resistance in Central Afghanistan, comprising some 800 regular fighters and 5,000 volunteers.

He had exhausted all other avenues, pleading with foreign governments to not abandon Afghanistan to the Taliban, he explained in a recent WhatsApp call from an undisclosed location.

"Everyone claimed the Taliban is modern, it's changed," he said. "But it hasn't changed – the killing, the violence has increased." His men were "standing against terrorism," he said, fearing that new terror networks would now emerge in Afghanistan under the Taliban's leadership.

The Hazara resistance leader said he had recently held talks with Ahmad Massoud, whose father, an ethnic Tajik, became famous for leading the resistance against the Soviets in the 1980s and then the Taliban. Shah Massoud was killed in a suicide bombing in 2001, but his son has been leading the fight against the Taliban in Panjshir.

Armed resistance "a recipe for disaster"

Until recently, the mountainous province north of Kabul was the only part of Afghanistan that had so far resisted the Taliban's sweeping offensive. Surrounded by mountains, the small valley has held out against both Soviet and Taliban invaders in the past.

Zulfikar Omid said Tajik and Hazara forces would unite against the Taliban, which is now equipped with state-of-the-art American weapons originally intended for the Afghan army. While he admitted that the resistance fighters' weapons, readily sourced from a burgeoning black market and even Taliban sources, might not be the most modern, he said the men's "willingness" and desperation made up for it.

But armed resistance by the Hazara could "be a recipe for disaster," fears Niamatullah Ibrahimi, a lecturer at La Trobe University in Australia and author of The Hazaras and the Afghan State. The Taliban could easily impose an economic blockade on the Hazara regions, he said, leading to mass famine. It might also result in more widespread massacres and revenge acts against the community.

Many Hazaras are fleeing, among them most of the well-educated, and that exodus would, Ibrahimi said, result in the Hazaras losing their voice in Afghanistan.

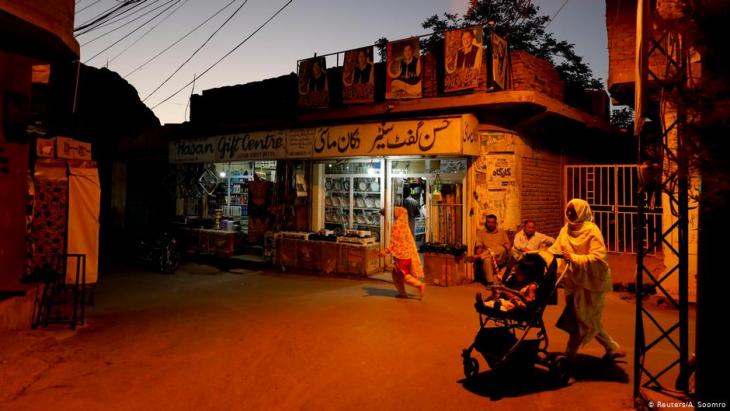

Seeking refuge in Pakistan

Up to 6,000 refugees, among them many Hazaras, have already made their way to Quetta in Pakistan, a city with a sizeable Hazara community, according to sources on the ground. Many are being housed in local mosques, others by local residents.

We spoke to one man, a 27-year-old labourer from Nimroz province in southwest Afghanistan, who had fled to Quetta in mid-August. The man had found refuge with a local mechanic, who had said he had taken in the man and seven other family members, including one child, as he had a spare room.

When the Taliban arrived in Nimroz, the Afghan man said, "everyone started running, trying to leave the country." At the border, he noted, there had been "chaos." The family had to bribe officials to cross into Pakistan, although the man was unsure whether they were Pakistani or Afghan border guards.

Pakistan has its own history of bloody sectarian violence against religious minorities, including Shias. But, he said, as long as the Taliban rule Afghanistan, they would not return.

Left behind

Back in Kabul, the 19-year-old Hazara woman was equally desperate to flee the Taliban's rule, even though her family did not qualify for evacuation.

While civil society activists, journalists and those worked for foreign militaries have qualified for evacuation, the Hazaras as an ethnic group have not been awarded such status by any foreign government.

These desperate Hazara men and women are being left to fend for themselves.

The avid cinephile, whose WhatsApp profile showed a smiling young woman, her scarf pushed back to reveal her long hair, was terrified she would no longer be able to continue her education under the Taliban.

"As a woman, an uneducated woman, the only thing expected from you is to bear children, to be a sex slave," she said, sobbing. She did not appear to harbour any hope that a freedom fighter would swoop in to save her and topple the regime, like in her favourite movie.

She continued to cry, then tried to compose herself.

"You cannot run away from the Taliban in Afghanistan," she said quietly.

Naomi Conrad, Birgitta Schuelke-Gill & Samad Sharif

© Deutsche Welle 2021