Detente over Kashmir following decades of conflict?

As recently as early 2019, all signs indicated that war between the two nuclear powers India and Pakistan was on the horizon. After an attack on a military convoy in Indian-administered Kashmir, the Indian Air Force dropped bombs on an alleged terrorist camp in Pakistan in early 2019. Despite Indian propaganda claiming that hundreds of extremists had been killed, the attack turned out to have been a failure. The bombs widely missed their target and landed in the forest. In retaliation, the Pakistani Air Force carried out attacks on the Indian-administered part of Kashmir, shooting down an Indian fighter jet during an air battle and taking its pilot prisoner.

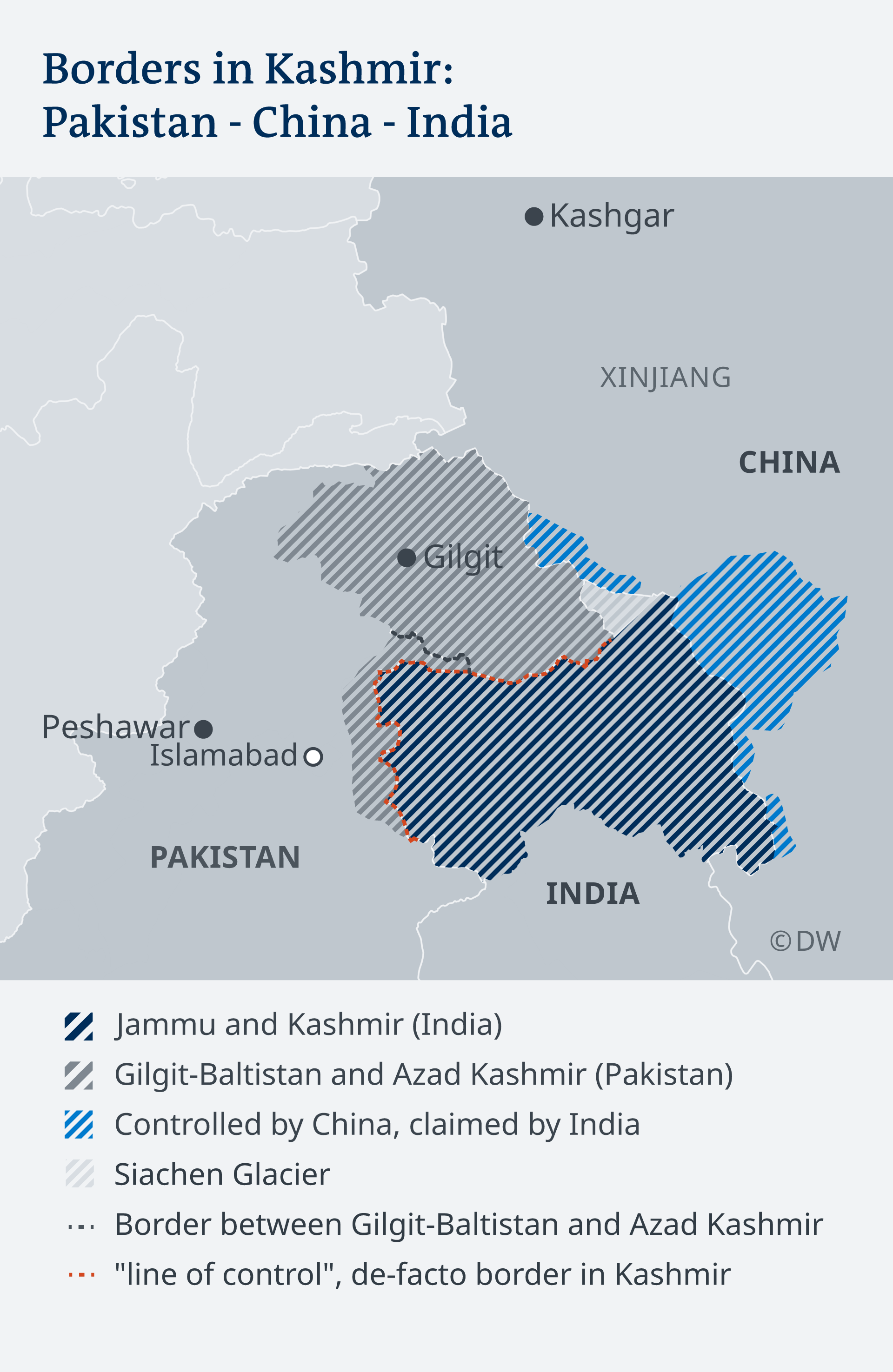

A few days later, reports and images of Pakistan handing over the pilot to India were splashed all over the media. At the LoC (Line of Control), the de-facto border between the two countries in Kashmir, the soldiers of both countries engaged in heavy fighting. Even though international pressure prevented a further escalation of the violence, the tension between the two countries remained. The Indian government's revocation of Kashmir's special status in August 2019 merely added fuel to the fire. People in both countries saw little hope of peace.

So it came as a surprise to many when a ceasefire was announced and that Pakistani Chief of Army Staff, General Qamar Javed Bajwa, called on India in a speech in March 2021 to "bury the past and move forward".

A short time later, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi extended greetings to his Pakistani counterpart, Imran Khan, on the occasion of Pakistan Day. Speaking in an interview soon after, Pakistan's foreign minister said that Pakistan was willing to enter into wide-ranging negotiations, as long as India was "willing to revisit" changes to the autonomy status of Indian Kashmir. Despite the martial rhetoric of the previous months, all of this heralded a period of detente. But why the sudden change of heart?

Secret diplomacy and change of strategy

There are several factors at play here. On the one hand, diplomats from the United Arab Emirates seem to have been active in the background, busily working to de-escalate the conflict – at least this is what the UAE ambassador to the U.S. claims. And indeed, it does appear that there were negotiations between the two countries that were mediated by the UAE. The UAE has traditionally had good relations with both countries. However, there are also signs – at least for the present – that both countries are changing their strategies. Both India and Pakistan are focusing on other challenges.

For India, the conflict with China on its northern border has gained in significance in recent years. The course of the border between China and India has always been a bone of contention and even led to the Sino-Indian War in 1962. The Indian army was defeated in this relatively short war and India lost Aksai Chin, a border region between Indian Kashmir and Tibet, to the Chinese. After several rounds of negotiations, a tacit understanding on the status quo of the LoAC (Line of Actual Control) was reached, an understanding to which both countries largely adhered in the decades that followed.

The construction of roads and military bases along the disputed border – by both India and China – meant that the conflict flared up once again. Both countries regularly accuse each other of border violations. Finally, the construction of a new road along the border to Aksai Chin was the straw that broke the camel's back. China claims the territory for itself. For India, this strategically important road is a supply route for the new Dolat Beg Oldie air force base in northern Kashmir. In June 2020, soldiers from both armies got involved in brawls at the Galwan river. Fists and truncheons flew.

Dozens of soldiers from both sides died in the first major border conflict since the 1960s. At other points along the frontier too there have been repeated clashes over the course of the 3,000-km-long border. For India, China has long developed into a much bigger challenge than Pakistan. In recent years, many Indian analysts criticised the excessive concentration of military personnel and resources on the country's western border with Pakistan, calling it a tactical error.

The reason being that during this time, China was easily able to build its military infrastructure along the border with India, thereby giving itself a strategic edge. In order to counter this development, India must now shift its resources and adapt its geopolitical strategy. In military terms, India undoubtedly lags well behind China.

The USA is strengthening India in this conflict in an effort to contain Chinese ambitions, which – as everybody knows – is seen by Washington as the greatest challenge to its hegemony.

The situation is compounded by the catastrophic consequences of the coronavirus pandemic for India. With millions of infected citizens, a healthcare system pushed to breaking point, and the as yet unforeseeable economic consequences of the pandemic, Prime Minister Modi's government has entirely new domestic challenges to cope with. The criticism of the BJP government's crisis management is growing and the Hindu Nationalists face the prospect of greater defeats in upcoming elections. A conflict with Pakistan would only aggravate the situation.

New challenges for Pakistan

However, the situation has changed a little in Pakistan too. Although Pakistan is holding fast to its traditional stance on Kashmir, it seems that there has been a re-think in a number of respects. On the one hand, Pakistan would like to recognise the so-called Northern Areas of Gilgit-Baltistan as a regular Pakistani province. This would be a far-reaching step and a move away from the UN resolutions, compliance with which Pakistan is vehemently calling for.

Although in 1949, the government of Azad Kashmir (the Pakistani part of Kashmir) transferred power in Gilgit-Baltistan to the Pakistani central government, which has administered the area ever since, it officially still belongs to the disputed region of Kashmir to which the UN resolutions relate.

The people of Gilgit-Baltistan have long been calling for the area to be recognised as a fully Pakistani province, but successive Pakistani governments have held back on doing so because they feared a weakening of their position with regard to Kashmir. In November 2020, the Pakistani government announced that it wanted to recognise Gilgit-Baltistan as an autonomous province.

In addition to the demands of the local population, the cementing of the strategic CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor) infrastructure project is playing a greater role. The CPEC passes through Gilgit-Baltistan on its way to China. By recognising the region as a full Pakistani province, the territorial question of the region for Pakistan would be settled, thereby protecting its future economic interests.

In addition to the CPEC, with the withdrawal of the Americans from Afghanistan, Pakistan is focusing more on its north-eastern neighbour once again. Islamabad considers a civil war or an unstable government in Kabul a threat to regional stability. Pakistan had long supported the Taliban as a stakeholder in the Afghan power structure and will continue to seek to influence the group during the post-American era too. Right up until the 1990s, however, the military doctrine of "strategic depth" played an important role in Pakistan's strategy. The doctrine saw Afghanistan as a retreat zone for Pakistani military units, should India invade Pakistan with ground troops and occupy the east of the country.

Even if this doctrine is out-dated from a current viewpoint, Islamabad sees in Afghanistan a way of building transit trade and opening up access to new markets in Central Asia. The Central Asian republic of Tajikistan is separated from Pakistan only by the narrow strip of Afghan territory known as the Wakhan Corridor. At the port of Gwadar, Pakistan offers Central Asian countries access to the sea and a doorway to global trade. Stability in Afghanistan is a key prerequisite for the development of such trade routes.

This is why the Pakistani government is keen to conclude trade agreements with Afghanistan and other Central Asian countries before the year is out. This would undoubtedly be a shot in the arm for the ailing Pakistani economy. A "hot" conflict on its eastern border with India would be counterproductive in this situation, which is why this détente comes at an opportune moment for Pakistan.

In short, the geopolitical situation is forcing both rivals to rethink. Whether these conciliatory noises do indeed lead to a longer-term détente between the two nations will become apparent in the coming months.

© Qantara.de 2021

Mohammad Luqman studied Islamic Studies at the Center for Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Marburg, with a research focus on Islam in South Asia. He is currently writing a PhD at the University of Frankfurt, on the relationship between religion and nationalism in Pakistan.