The power of reflected suffering

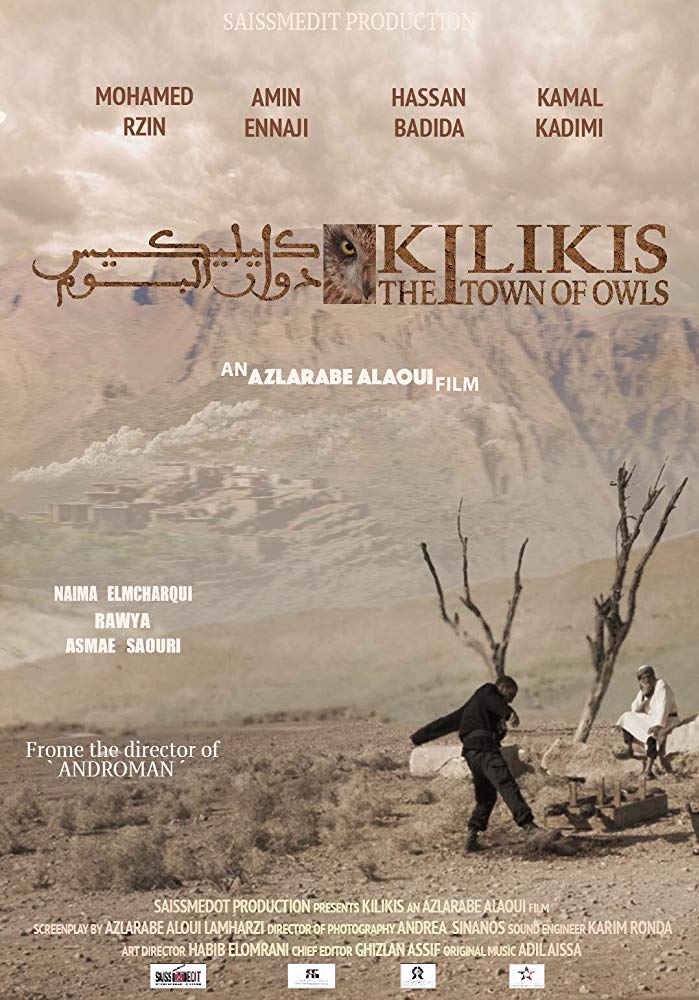

That night was like no other for one isolated village in a remote part of Morocco. The soldiersʹ voices got louder, alongside the sound of their army boots as they hit the ground in time with each other. A human chain of blindfolded people moving towards a building comprised of dimly-lit cells. Weary sighs hidden in the darkness, save for a few traditional lamps, nothing seen. Then comes the sound of the adhan to announce the dawn and the opening scenes of the film "Kilikis, the town of owls", directed by Azalarabe Alaoui.

The military prison is the focus of events in this cinematic work. The story revolves around soldiers guarding people portrayed as "enemies of the homeland and religion", but the truth is not so simple. One day the conscience of one of the guards is awakened after he becomes fed up with his own cowardice. He attempts to do something brave once in his life, even though it may lead to his death. But the price he pays for his act of rebellion is high, not just for him but also for those who refused to toe the official line.

The film ends without the audience knowing the fate of either those who rebelled or those who toed the line, like the words of the Chilean poet Neruda: "They can cut all the flowers, but they canʹt stop the spring". It comes immediately after the morning light has broken into the dingy cells, following a night in which the guard had a breakdown because a female dog he was raising died and because a critically important file somehow got out of the prison. The latter gives the viewer new hope, having been soaked in grief and pain for more than an hour and a half.

Probing the wound of Tazmamarat

On 31 July 2018, the film won the Best Director Award at the Oran International Arab Film Festival, the first showing of this work outside Morocco since it was screened at the Moroccan National Film Festival in Tangier.

"Kilikis, the town of owls" does not refer to a particular time or place, except for the director Alaouiʹs preface in which he talks about "a place in the desert laid waste by nature and by man", and that it dates back to when he was eight years old.

It doesnʹt take much for the viewer to connect this with the appalling prison of Tazmamarat, which was finally closed down in autumn 1991. Dozens of military and civilian personnel were imprisoned there during the late King Hassan IIʹs reign, either on charges of taking part in the attempted military coups in 1971 and 1972 or for political reasons.

"Town of the owls” is not the first film to talk about what are known as the "Years of Lead" in Morocco. There have been many such films since the state began a process of reconciliation with its past, but it is the first time any full-length film has dealt with the story of Tazmamarat.

Like many Moroccan films, this work was supported by the Moroccan Film Centre, which is affiliated to the Ministry of Culture and Communications. It also won a partnership with the National Council for Human Rights, which was established by the Moroccan state to consolidate a culture of civic rights in the Kingdom.

The film critic, Fuʹad Zuweirik, says that the director "portrayed the tragedy in a novel fashion, without exaggeration or melodrama, giving viewers an emotionally measured dose, balanced between fact and fiction, without resorting to direct political messages that might have dissipated the intellectual and visual focus."

Why focus on the jailer?

Of the criticisms made about the film, the most significant was the decision not to show the prisonersʹ faces, notwithstanding the fact that they, with the jailers, represent the two main threads of the plotline. Alaoui explains that he is playing with mirrors in his film: "the prisonerʹs suffering is reflected in the face of his jailer. I am using the eloquence of invisibility, which can be even more potent than physical embodiment. Not seeing something gives it enhanced reality. The film can therefore be hard going for viewers, even though there are no actual scenes of torture."

Alaoui goes on to say that he opted not to show the detaineesʹ faces, not because he wants to make them disappear or to downplay them, but because he wants the viewer to embrace one of two interpretations: the first elevates the detainees to a level of sanctification, almost akin to the saints whose faces are not shown in numerous films. The second involves each viewer trying to imagine his own face in place of those absent faces, to make him feel that he too could have been subject to the same miserable fate.One former detainee at Tazmamarat, Ahmed al-Marzouki, did not hide the fact that the film failed to meet his expectations: "in the first place, I salute any artistic or literary work which touches on the suffering in this jail and I salute the directorʹs courage in tackling this sensitive subject. That said, had the director met some former inmates while he was writing the script, many of the misconceptions in his film could have been avoided. Alas, it seems as if he only read what has been written about the detainees."

Marzouki strongly criticises what he sees as a kind of rehabilitation of the former prison guards. He says they were horrific executioners and committed serious crimes, including practically torturing prisoners to death. The only exceptions were three guards who helped detainees to varying degrees. "There were no guards in Tazmamarat who were torn between conscience and duty," says Marzouki, who notes that the prisonersʹ suffering in the film was understated. Even the way in which that suffering was presented in a scene about serving meals to the prisoners was not real. Indeed, the guards used to humiliate the prisoners at most meal times.

Historical fact or cinematic fiction?

As might have been expected, the film has stirred up the age-old debate between cinema and history. Should fictional films present the historical events that inspired the narrative exactly as they were, or does the director have the right to construct the scenario as he sees fit, as long as he makes clear that the film is not necessarily telling a true story. The director Alaouiʹs response is that he has not enlisted history to serve his artistic point of view. Indeed, he did not rely on history at all: "the scenario was inspired by the detention camps which surrounded the region where I lived and by the stories I was hearing. I did not mention a time or a place or a name in any scene. The movie is about prisons, and it may be in Morocco or elsewhere, since injustice can happen anywhere."

Marzouki, the author of "Cell No. 10", in which he presented horrific testimonies about his years of detention in Tazmamarat, believes that the film should have stuck to the events as they happened. "It should have been more honest in dealing with the truth, so as not to confuse audiences about the awful nature of this prison. Only then should the director add his artistic touches, as he chooses." Marzouki said the film downplayed the awfulness of the prison by including scenes which were completely at odds with what actually happened.

On the other hand, the critic Zuweirik says the film is a long way from being Tazmamarat prison, in shape or substance. "This prison may have formed the germ of Marzoukiʹs idea, but Alaoui's film doesnʹt necessarily represent any specific prison, nor is it set in a particular historical period."

Zuweirik adds that "time and place" in the film are all-embracing and absolute; it may symbolise the present, take us back to the past, or move us to the future – and it may transport us to any corner of the world. That is the source of the filmʹs power. As he says, we need to remember that the film is a work of fiction, not a documentary, and therefore cannot be held to account in historical terms.

Ismail Azzam

© Qantara.de 2018

Translated from the Arabic by Chris Somes-Charlton