Naive Aestheticism

Roger Diederen, curator of the Kunsthalle (art gallery) of the Hypo Cultural Foundation, in Munich has long wanted to mount a large-scale exhibition on the Orientalists, not least because, "given the European migration debate, the Orient has become a topic of tremendous importance".

Any visitor to the exhibition wishing to explore this aspect of the Orient's significance, however, is going to be disappointed, to say the least. Whereas issues of integration are usually central to migration discourses, the Munich gallery, by contrast, inhabits its own rather rarified and exclusive sphere. The harsh social reality of areas such as Berlin's Kreuzberg or Neukölln stands in stark contrast to the dignified, hallowed atmosphere of such art galleries.

Inexhaustible reservoir

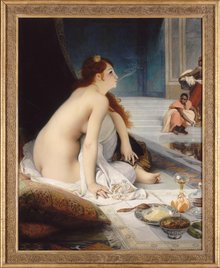

The exhibition "Orientalism in Europe" (January 28 – May 1) presents a visual realm that is full of images of opulent and often sexist exoticism. Until the beginning of the modern period, most western European artists were obsessed by the sensuously sprawled forms of odalisques, the female slaves of the Turkish harems.

They saw the Holy Land, too, as an inexhaustible reservoir for their projections of the East. It was Palestine in particular that became a symbol of a Christian past, the recovery of which became the dream of many artists, including Wilhelm Gentz (1822–1890). In his monumental "Entry of Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia into Jerusalem", of 1876, the German artist immortalised the Prussian prince's progress into the city through the Damascus Gate as a military triumphal procession.

Prussian colonial ambitions are certainly reflected in the painting, but the artist may also have been inspired by the crusader legend, according to which the next Christian prince to enter the city through the Damascus Gate, following the failure of Gottfried von Bouillon's attempt in 1099, would wrest Jerusalem from Muslim control for all time.

Colonial atavism

This colonial chauvinism is, of course, well enough known, but it never fails to arouse feelings of unease. One is reluctant to be reminded of the cultural heritage one believed had finally been left behind in the post-colonial period. The exhibition in Munich brings it right back, with a vengeance. The orientalising human studies of the 19th century are meticulously documented in the busts by Charles Cordier and sketches of Jean-Léon Gérôme or Charles Gleyre. Among their major inspirations was a treatise published in 1829.

In "Physiological Characteristics of the Human Races" the French physician William Frederic Edwards argued that the study of the physical characteristics of peoples would provide evidence to show which race was made to rule and which destined to serve. For Edwards, physiology was a fixed quality, regardless of environmental factors – a concept of history that renders political and social processes incidental.

Nothing but "pretty pictures"

Anyone who expects the Munich exhibition to expose the shocking rationale behind the colonial mentality for what it is is going be sadly disappointed. The studies in the exhibition catalogue are given an almost neutral presentation as "Academic Orientalism?" – though the question mark added to this phrase is curiously absent from the information boards in the exhibition.

Is it possible that Edward Said's famous thesis has failed to penetrate the inner circles of the Munich curatorial world? In his groundbreaking 1978 work "Orientalism", Said dissected the Eurocentric view of the Orient as an instrument of the colonial powers. It was the British and the French, above all, who had turned the "Oriental" into their inferior counterpart in order to justify their rule over it.

"And this in its essence is something that can hardly be contradicted, says Silvia Naef, Professor for Arab Cultural History from the University of Geneva. The fact that the Munich exhibition is trying to do just that, however, is something that does not surprise her. "There are always those who try to detract from Edward Said's analysis. What they offer instead are attempts to consider the Orientalist paintings in terms of their stylistic aspects or as an aesthetically fascinating art historical phenomenon."

This is the approach favoured by the Munich curators. Edward Said's theories are completely ignored. What we have instead is an exhibition catalogue that opens with a quotation from Goethe from 1815: "My object is (...) to link the West and the East in a cheerful way."

The historian Edhem Eldem also finds the uncritical reception still given to Orientalism problematic. At the same time, however, the historian from Bogazici University in Istanbul warns against demonising the 19th century artists or assuming that they were motivated by a racist or imperialist agenda. "They were simply products of their environment and of the dominant mentality of the times in which they lived," he says.

The Orient without the Oriental

Not demonising the artist is one thing. To want to present Orientalism as a cheerful, harmless, more or less attractive phenomenon, is something else. What it amounts to is an unadulterated monologue – and it is precisely that that is on offer in Munich. No attempt has been made to include the Oriental Orientalist perspective, for example.

Perspectives such as that of the Syrian Tawfik Tareq, who, though he also chooses to depict "Mohammad XII, the Last King of Granada" surrounded by belly dancers, does so only, as Silivia Naef points out, to criticise how little attention the monarch gave to his kingdom.

Sehzade Abdülmecid's painting "Beethoven in the Harem" (c. 1900), which shows the residents of the harem fully clothed and playing musical instruments might also have opened a door to discussion.

In answer to the question of why it is that these and other Ottoman Orientalist perspectives are missing from the exhibition, Curator Diederen rather dismissively refers to what he calls their stylistic "third-rate" status and to the fact that he wanted to focus on European Orientalism. This comes across as arrogant given that a great many of the art works that are on show in Munich cannot themselves be said to be of the first rank.

Besides, one Oriental Orientalist, Osman Hamdi Bey, did make it into the exhibition. It is well known that this pupil of Jean-Louis Gérôme and Louis Boulanger painted for the European market, providing exactly what it wanted to see: a picture postcard Orient, though his version was just a little more dignified, a little less eccentric than what was being turned out by his European contemporaries.

A mere fig leaf, then, for an exhibition that ultimately succeeds only in contributing to the consolidation of stereotypes – 40 years after Edward Said and right in the middle of a debate on migration. That is just about as naive as it gets.

Mona Sarkis

© Qantara.de 2011

Translated from the German by Ron Walker

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de

Qantara.de

The Bidoun Library Project

A Treasure Chest of Oriental Pulp Fiction

The Middle East has long been a source of fascination for artists and writers, especially in the West. The Bidoun Organisation has created a travelling exhibition that brings together some 1,000 posters, cartoons, catalogues and curiosities that show how distorted the clichés of the Orient were, even post-1945. Amira El Ahl reports from Cairo

Arab Photographers' View of the "Orient"

Looking into the Blind Spot

Frequently criticized as they are, images that "orientalize" Middle Eastern subjects are widespread and well known. The Arab Image Foundation, however, presents other views of this part of the world. Browsing its online collection is a voyage of discovery, says Mona Sarkis

Edward Said's "Orientalism"

The Orient beyond Cliché

The Palestinian-American literary scholar Edward Said (1935 – 2003) is required reading for anyone talking about Islam today. His main work, Orientalism, recently came out in a new German translation. Stefan Weidner read it for Qantara.de

Edward Said's "Orientalism" in Arab Discourse

Instrumentalised on All Sides

Edward Said published his seminal work Orientalism thirty years ago. For western academics, the book emerged as the manifesto of theoretical decolonisation – but how was his intellectual legacy received in the Arab world? Markus Schmitz has the answers