Where the uprising began and still lives on

Why Daraa? What's so special about this city of 80,000 inhabitants in southern Syria, the capital of the province of the same name? Nothing, really, is the simple answer. People there make a living from farming, local businesses and border trade with Jordan (both legal and illegal). They are conservative Sunnis, religious in a moderate, unpolitical way, and they define themselves by their membership of family clans and tribes.

And yet the question, which was worth asking four years ago, is still worth asking today. After all, it was in Daraa that the first big protests took place in March 2011; it was there that the first demonstrators died, the first tanks rolled in and the first soldiers deserted, and it is Daraa Province where the moderate rebels of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) still represent a notable military power. It stands in contrast to the rest of Syria, which is dominated by militias allied to the regime, Islamists, jihadists or Kurds.

However, it is its average nature, and not some special quality, that Daraa has to thank for its exceptional role. The area brings together all the reasons that drove people onto the streets in Syria: state despotism, economic injustice, secret-service oppression and a lack of political freedom and personal prospects. This was an oppressive and incendiary combination.

In 2011, Daraa's inhabitants had suffered years of drought and a bureaucracy that was getting out of hand. The secret services were interfering in people's everyday lives, controlling farmers and business people by only handing out seeds and permits in return for bribes, and shamelessly lining their own pockets. The secret service chief Atef Najib, Assad's cousin and governor in the South, was responsible for this corruption and despotism. Arrogant and unscrupulous, he went a crucial step too far in March 2011.

The spark that ignited the uprising

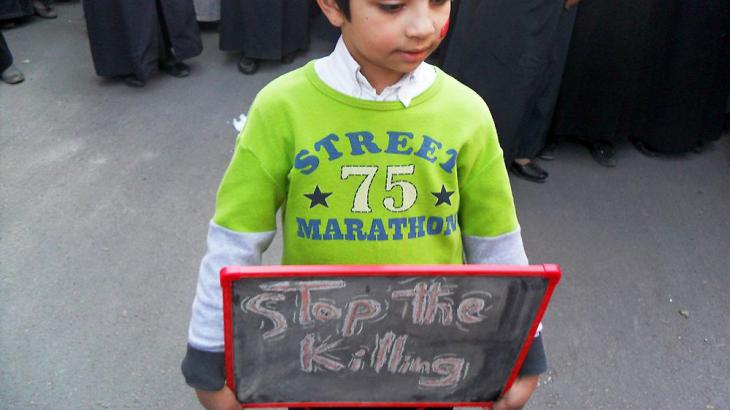

Inspired by the turmoil in Tunisia and Egypt, schoolchildren painted slogans criticising the regime on the walls of their school. They were arrested and tortured. Their families went to Najib to demand the release of their children, but to no avail. "Forget these children; go home and make new ones, and if you need help, send your wives to us," he is reported to have said. It was one indignity too many. On 18 March, hundreds of Daraa's inhabitants took the rage they had been suppressing for years onto the street.

The regime responded with violence. Four demonstrators were shot dead; their funeral procession turned into the next protest march. Over the weeks that followed, towns and cities all over Syria showed their solidarity with the resistance. Right from the outset, Assad viewed the demonstrators as terrorists and foreign agents. In an effort to make this propaganda come true, he released jihadists from prison, stoked religious hatred and sent secret service provocateurs to cast the uprising in a bad light.

By the summer of 2011, the revolution had spread and become a country-wide but decentralised movement, with millions of Syrians demonstrating in dozens of places. Assad felt threatened and crushed the protests in a targeted manner, deploying snipers, tanks, surface-to-air missiles, fighter jets, chemical weapons and barrel bombs.

The revolution then became militarised and radicalised. Foreign agents got involved: first Iran, the Lebanese Hezbollah and Russia on the side of the regime, then Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey in support of the opposition. The West did a lot of talking, but provided little help, so the national, moderate rebels and the civilian resistance were soon at a disadvantage. Attracted by the crumbling state, al-Qaida groups started arriving in the country in 2013; today, IS and the al-Nusra Front are the most powerful of Assad's opponents.

Half-hearted support

Only in the South do moderate rebels still have significant influence. The al-Nusra Front may be present in Daraa as well, but unlike in the North, different FSA brigades work together more effectively there. This is a result of better organisation and the fact that they have foreign support. A US-led "Military Operations Center" (MOC) in Jordan is channelling military aid to the allied groups in Syria, consisting of fighters from the region who first joined together as the "Daraa Military Council" and later as the Southern Front and the First Army.

Here too, however, support is half-hearted, meaning that the FSA has to work with the al-Nusra Front on large operations. But so far in Daraa, entire units have not been completely destroyed or taken over by al-Qaida offshoots, as they have in the northern provinces of Idlib and Aleppo. Al-Nusra may be militarily stronger than the moderate rebels, but until now, the FSA in the South has had two crucial advantages: it has both more fighters and the backing of the population. Elsewhere, it has lost both of these things.

In the North, rebel units have to organise their own support by meeting intermediaries from Washington, London, Doha or Riyadh in the Turkish border area. In addition, they are also still competing with each other for a few financiers, which makes co-operation more difficult.

The FSA in the South, meanwhile, has the MOC: a contact that pools foreign support (from the USA, the UK, France, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Jordan) and provides organised, if limited, financial support. The chain of command that has long been called for is, therefore, present in the South, at least in a rudimentary way.

Alongside this, civilian organisations are looking after administration and supplies in the "liberated" areas, says Khaled Yacoub Oweis, a former Reuters correspondent in Syria and currently a fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) in Berlin. Oweis has investigated the situation in the South and discovered that the infrastructure has largely remained intact, unlike in the North. This is because both sides depend on each other: Daraa provides water to the neighbouring, regime-controlled province of Sweida, while Sweida provides Daraa with electricity.

Clouded prospects for peace

Overall, power relations between the regime and the opposition in the South seem more balanced, which in Oweis's opinion also improves the chances of local ceasefires. To date, ceasefires almost everywhere have amounted to a capitulation by the rebels, and the regime has used them to re-establish its power.

The opposition's reaction was, therefore, understandably sceptical when the UN special envoy Staffan de Mistura suggested a temporary freeze on the fighting in Aleppo. Oweis believes the South is better suited to implementing lasting ceasefires because there, both sides have equally strong negotiating positions, which could lead to long-term compromises.

But Assad has other plans. With an offensive in the South supported by Iran and Hezbollah, he is currently trying to weaken the national resistance and drive moderate rebels into the arms of al-Nusra and IS. Then he can declare his merciless war on Syria's civilian population to be a fight against terror in this region too.

The region is also strategically important, as a connecting axis between Damascus and Jordan, and because of its proximity to the rebel-controlled suburbs of the capital and the Golan Heights, occupied by Israel, where the al-Nusra Front already holds positions.

Instead of simply concentrating on IS in Syria, as it has been doing since the summer of 2014, the West should stop neglecting the origins of the radicalisation: Assad's brutal reign. This goes for the South in particular, where the MOC has long had contact with the counterparts it has been asking for and who are in a position to combat the jihadists.

However, if they are to do this, they must do one thing above all else: they must lead the fight against Assad. Only as the spearhead of the resistance will the FSA pull the rug from under the radicals' feet. Only when they can do without military support from the al-Nusra Front will the latter lose its significance and attraction.

Kristin Helberg

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin