Who owns the Nile?

Many residents of the Ethiopian capital are well equipped with candles, generators and an ample supply of patience in order to cope with the regular power outages in Addis Ababa. During a recent state visit, Egyptian President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi experienced first hand a power blackout that lasted a number of hours. It was almost as if the Ethiopian capital wanted to demonstrate to him the urgent need for electricity from the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).

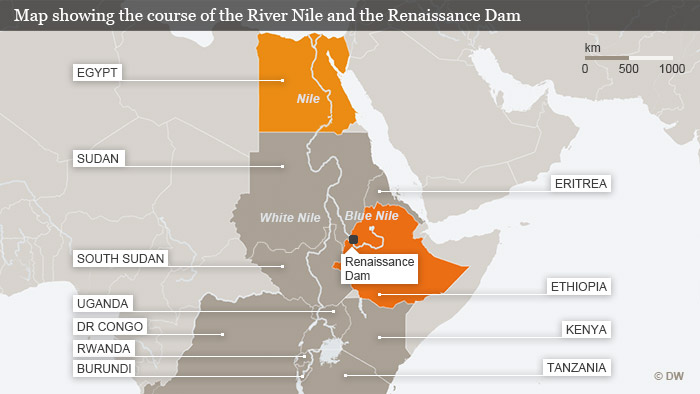

The gargantuan project, located on the upper course of the Blue Nile in Ethiopia, has been a source of tension between the neighbouring states for years. The reason for this is that Egypt is also heavily dependent on the river. In 2013, Sisi's predecessor, Mohamed Morsi, even indirectly threatened Ethiopia with war out of fear his country could suffer a water shortage.

Water for prosperity

For the past few years, the government in Addis Ababa has been ambitiously pursuing the construction of the largest hydroelectric project ever to be built in Africa, located in the Benishangul-Gumuz Region of Ethiopia near the border with Sudan.

With a population of around 90 million, Ethiopia is the second most populous country on the continent after Nigeria. This aspiring economic power aims to satisfy its energy requirements through the construction of a series of dams along the Blue Nile. The centrepiece of this policy is the over 3-billion-euro GERD project, which upon completion should produce 6,000 megawatts of electricity – as much as five nuclear power plants. Ethiopia thereby aims to achieve greater independence from crude oil imports and simultaneously provide a stimulus for its emerging industrial sector. In addition, the government in Addis Ababa plans to alleviate its chronic shortage of foreign currency by selling up to 2,000 megawatts of energy to its African neighbours, including Egypt. Although the first supply agreements have already been signed, many conflicts remain unresolved.

Some 160 million people live in the Nile Basin. The desert nation of Egypt fears that upon completion, GERD will quite literally leave Egyptian farmers high and dry with nothing to irrigate their fields, claiming that once the 1,680-square-kilometre reservoir has been flooded, water will evaporate in the heat. Egypt already experienced something similar with the opening of the Aswan Dam in 1971. Egypt and Sudan have even invoked colonial treaties dating back to 1929 and 1959, which guarantee both countries an almost 90 per cent share of the water flow from the Blue Nile and the White Nile as well as ensuring the right of veto over any construction plans.

The Nile belongs to everyone

On 23 March, after years of controversy, the countries of the Nile Basin finally reached a basic agreement. Under the mediation of Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir, Egypt's President Sisi and Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn signed a treaty in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum on the construction of the dam. "We have signed a landmark agreement that will form the basis of all our future negotiations. We, for our part, will keep our word," said Desalegn. "We now hope that further steps will follow, allowing us to achieve our common goal," said Sisi.

These are unusual signals from the leadership in Cairo, especially since Egypt has remained politically unsettled since early 2011 with the overthrow of its long-term ruler Hosni Mubarak. Both the former Islamist President Morsi as well as the current head of state, President Sisi, have used this conflict with Ethiopia as a diversionary foreign policy tactic. Negotiations were suspended and it was only in the autumn of 2014 that an Egyptian delegation visited the dam construction site for the first time.

With the signing of the treaty on 23 March, the three Nile Basin states took a significant step towards dividing up the river water, says Abel Abate Demissie from the Institute for Peace and Development in Addis Ababa. "The greatest areas of contention, which gave rise to the mistrust between Egypt and Ethiopia, have been resolved," claims the analyst. "The treaty will undoubtedly result in better relations between the three countries, and not only in terms of water and the economy, but also with respect to peace and security, regional integration and other concerns extending far beyond these issues."

A tactical conciliatory course

But Cairo's current "sunshine policy" extends further than the construction of GERD and a series of smaller dams in Ethiopia. Relations between the two countries were icy under former President Mubarak, who survived an assassination attempt in Addis Ababa in 1995. Sisi, however, is concerned about the fragile security situation in the region and is therefore interested in improving relations with Ethiopia as a stabilising power, especially as the African Union is based there.

The government of Sudan, which acted as mediator in this dispute and also plans to invest heavily in hydroelectric power, is planning the construction of its own dams. It therefore has an optimistic view of the situation. "This dam is a blessing for Ethiopia and a huge benefit for the rest of us," announced Mutaz Musa Abdalla Salim, the Sudanese Minister of Water and Energy. Perhaps the Egyptians will soon see things in the same light. The gigantic dam is scheduled to be completed by 2017.

Ludger Schadomsky

© Deutsche Welle/Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by John Bergeron