In the beginning there was violence

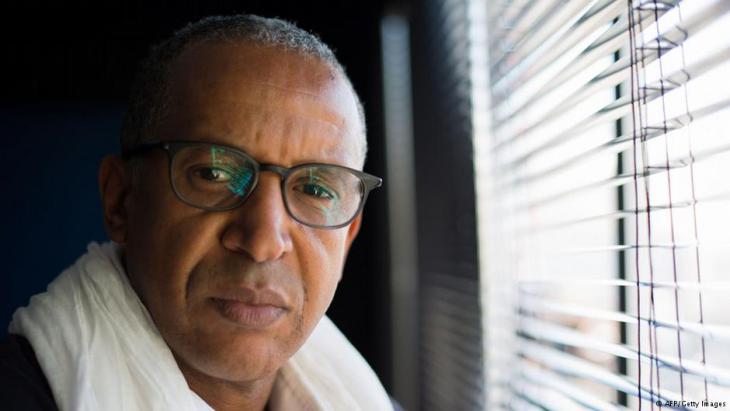

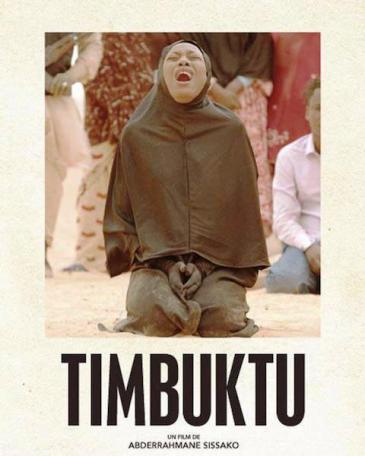

In 2012, when news of the advance of Islamists in Mali reached the outside world, reports of their nine-month occupation of the northern part of the country included an account of the execution of a man and a woman who had been living together out of wedlock. The film director Abderrahmane Sissako ("Bamako", 2006), who was born in Mauritania in 1961 and grew up in Mali, turned this news item into a brief but harrowing episode in his new film "Timbuktu", in which a couple is stoned in accordance with Sharia law.

The incident takes place more or less in the middle of the film. It is bracketed by scenes at the beginning and the end in which men speed through the desert in a jeep, aiming first at a gazelle, and then finally at a fellow-human being. The black flag of jihad flutters above them.

In short, violence has the first and the last word in this film, which was shot against the backdrop of the brown mud-walled houses of Timbuktu and the desert sand of the southward-advancing Sahara. The triumph of evil comes up against the gentleness of the conquered, who in most cases face the occupation in silence.

"Shouldn't we leave?" the nomadic woman Satima (Toulou Kiki) asks her husband Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed dit Pino). Their neighbours have long since packed their things and moved on to a safer place with their cattle herds. "It will pass," her husband reassures her, meaning the armed strangers who came from the north and who need an interpreter to communicate with the locals because they don't understand the Tuareg language Tamasheq.

Out here, on the banks of the Niger River, peace seems to reign for the moment. Lounging on soft cushions, Kidane enjoys his pipe. His wife sits next to him, along with their lively little girl, who gazes up at her father adoringly. It's hard to picture a more idyllic family scene.

Yet on that same day, disaster strikes for all those gathered here. A cow from Kidane's herd has trampled a fisherman's net, and the fisherman spears the cow in retaliation. In the heat of the dispute, Kidane in turn kills the fisherman. According to Sharia law, this spells death for him if the family of the murdered man refuses to forgive him. And from their hard, angry faces it is evident that forgiveness will not be forthcoming.

Sissako couches this story in the wider context of the Islamists' demonstration of power. Yelling out through megaphones up and down the alleys, the jihadis make it clear that music-making, smoking, alcohol, and loitering in the streets are now punishable offences. They strictly monitor compliance with the new dress code, punish young people for playing guitar and singing, publicly flog a woman and carry out stonings.

Rite of violence

Kidane's execution is imminent. Then a sudden cry, an act of rebellion, breaks through the unrelenting regimen. Not the admonitory words of the imam spoken to the Islamists, but a woman, Satima, intervenes in the rite of violence. The whole film has been building up to this sudden reversal, almost like a Russian Revolution saga from the 1920s – a cinematic legacy that left a deep impression on Sissako when he studied directing in Moscow.

European viewers may find the ancient caravan town with its narrow alleyways, madrassas and mosques fascinating. It may also be captivated by the sight of a sand storm sweeping across the desert. Although Sissako makes the most of the lure of the exotic setting, the city, the desert and the night sky are merely backdrops for a human drama that finds its culmination in the expressions on the characters' faces: gentle and friendly faces on the one hand and the by turns torn and devious countenances of the pioneers of an Islamist state on the other.

At one point, human compassion even seems about to put an intermittent stop to the ideological madness, namely when the judge questions Kidane and yet is unable to help him, despite his sympathy for the father and his child, who is soon to be orphaned.

"Timbuktu" attempts to overcome the nightmare of Islamist rampaging – the nightmare of every good Muslim – by summoning gentleness as a source of resistance. Sofiane El Fani's camera, zooming in on the faces and then panning across the city and the landscape, lends the film its majestic imagery. Also worthy of note is Amina Bouhafa's music, which draws on both traditional and modern elements, providing a fitting accompaniment to the depicted events.

Why don't we see more films like this coming out of Africa? They do exist; we just have to seek them out.

Hans-Jörg Rother

© FAZ 2014

Translated from the German by Jennifer Taylor