Idlib: Collapsing Turkish lira makes life harder than ever

Khadija lives in Idlib, the capital of the Syrian Idlib province. The burden of responsibility weighs heavily on her shoulders. She has become her family's main breadwinner, and provides for her twin brothers, who were born with Down's syndrome. "I work a lot," she says. "My father used to be able to provide for us on his own. His salary today is only enough for the food we need."

46-year-old Khadija lives together with her father and his new wife, and her 40-year-old twin brothers. She has never married: "When my mother fell ill and then died 16 years ago, it was clear to everyone in the family that I would take on the responsibility for my brothers," she says. "I've become more than just their sister, but I love taking care of them," she adds. She cooks their favourite meals, buys their clothes and spends as much time as possible with them.

Currency switch to the Turkish lira

However, Khadija also has two paid jobs to make ends meet. She works in a hair salon, where she gets a share of the turnover. Her second job is teaching hairdressing to women at the Idlib Women's Centre. "The work is fulfilling. But I have to work more to improve our financial situation. Everything has become expensive."

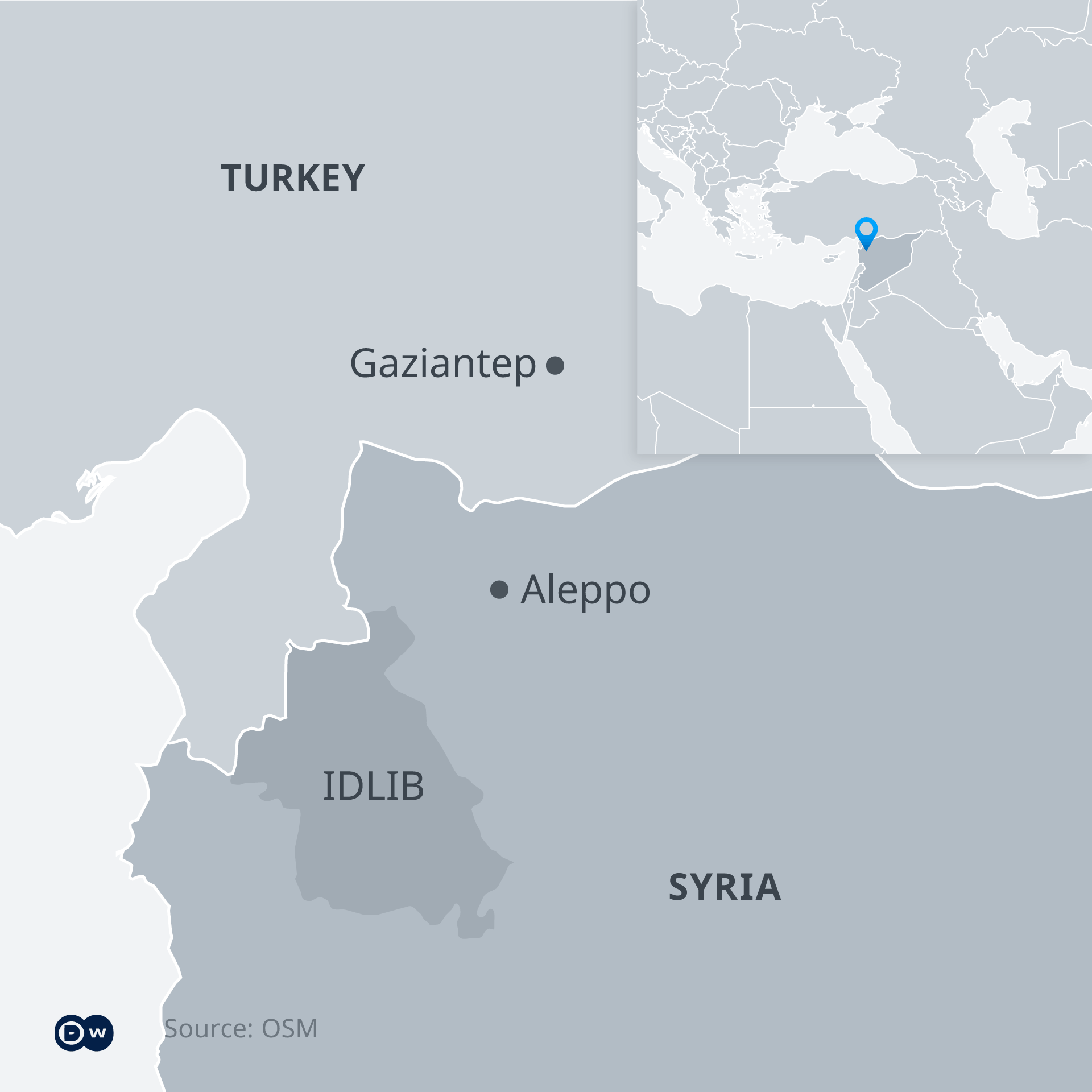

Idlib province in north-western Syria, near the Turkish border, is the last region under the control of Syrian rebels and Islamists. It is predominantly under the control of Islamist militias of the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) group, which emerged from the Nusra Front.

In late 2019, the local currency, the Syrian pound, was massively depreciated. The reasons were manifold: The economy had no chance of recovery after years of war and sanctions against the Assad regime and various companies were making life more expensive. This was exacerbated by the dramatic economic crisis in neighbouring Lebanon, which has also had an impact on Syria.

Eventually, in summer 2020, the Islamists introduced the Turkish lira as the new currency throughout Idlib province, replacing the Syrian pound. The de facto local authorities had hoped that the currency change would protect the region from the imminent economic collapse. The currency change took place just before the new U.S. sanctions against the Syrian government came into force, putting even more pressure on the Syrian currency, which was already in freefall.

Depreciation of the Turkish lira and rising prices

However, the Islamists did manage to stabilise prices in the Idlib province for eighteen months, Syria expert Zaki Mehchy of the British think tank Chatham House in London, explained. "But now that the Turkish lira is deteriorating, it is affecting the living conditions of ordinary citizens in Idlib," he says.

Khadija confirms this whole-heartedly. According to various estimates, around four million people live in Idlib province, over one million of them in refugee camps. Many have already fled several times within Syria. About 75 percent of Idlib province residents are in need of humanitarian assistance, according to Human Rights Watch. The grim situation is exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the constant bombardment of the southern areas of the region by the Assad regime and its supporters. "We have to endure a lot here, life is really not easy," says Khadija.

When the Turkish lira was introduced as a means of payment in 2020, the exchange rate was 6.8 lira for one U.S. dollar. In the meantime, the dollar is at 12.9 lira (as of 1 December 2021). "When the lira lost so much value, stores and merchants immediately raised prices," Khadija tells us. There are people who earn just 100 lira a week, she says. "How can you afford paying 157 lira for a gas bottle for cooking?" she asks.

Goods from Turkey or the black market

For example, Watad Petroleum – an oil company linked to those in power in Idlib – raised fuel prices as the value of the Turkish lira fell. While it is unclear who is behind Watad, they are known to source oil for north-western Syria mostly from Turkey. In general, almost all goods traded in the province come from Turkey. They enter Syria through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing. "Even we in the hairdressing salon only use products from Turkey. But of course, goods from Syria are still in circulation," Khadija reports.

"In general, the resources in Idlib are not diverse enough to cover the needs of local communities," says Zaki Mehchy. Wheat, for example, is grown in the region, but it cannot meet the region's bread needs. "That's why they depend a lot on goods coming from Turkey or from regime-controlled areas or even from the Kurdish controlled areas."

The goods that enter Idlib from inside Syria are smuggled. These are often more expensive because the international sanctions have contributed to an increase in the prices of everyday goods in the areas controlled by the regime. Smugglers then exploit the situation to optimise their profit margins. "And it is ultimately the end consumers in Idlib who pay the price."

The next disaster is looming

Khadija and her family in Idlib city are grateful that they have their own house, despite the fact that they can only just make ends meet. "Other people are much worse off here. They live in tents and depend on financial aid," she says. Till Kuster is the head of the cooperation department at the organisation Medico International. He says the next disaster is looming – driven also by the onset of winter and the COVID-19 pandemic. "Most workers and employees get their daily wages paid in Turkish lira and live on that basis. If things continue like this, people will soon hardly be able to afford bread. Currently, the only way to help is through food donations or money," he said.

For Khadija, however, leaving Idlib is out of the question. Escaping with her two brothers would be impossible anyway. "Where would I go with them?" she asks. "Besides, I think it's important to give the women here an economic perspective by teaching them my trade," she says. "I want them to be able to support themselves."

© Deutsche Welle 2021

Translated from the German by Jennifer Holleis

You may also like:

Syria and the Arab world: Assad's return to the fold

Loyalty and legitimacy in Syria: Bashar al-Assad's staging of the presidential election

Reconstruction in Syria: The next battleground

Russia, Israel and the Syrian conflict: Curbing Iran's influence