Iran: A Great Cinematic Nation

-

-

Jafar Panahi: opening up a window to the world. Directors from Iran are currently back in the international spotlight. Currently, they are the focus of not one, but two German film festivals at present. Despite having been under house arrest in Tehran for quite some time now, Jafar Panahi was able to make the film Closed Curtains, which won the Silver Bear at the Berlinale in February 2013 (the photo above is a still from the film). -

Explosive premier: despite the oppression of both the Shah's regime and the religious governments that came to power after 1979, Iranian directors have always managed to make outstanding films. The German premier of Manuscripts Don't Burn by Mohammad Rasoulof, a tale of a system of surveillance and intimidation, attracted a lot of attention. It was named "Best Political Film" at the Filmfest Hamburg. -

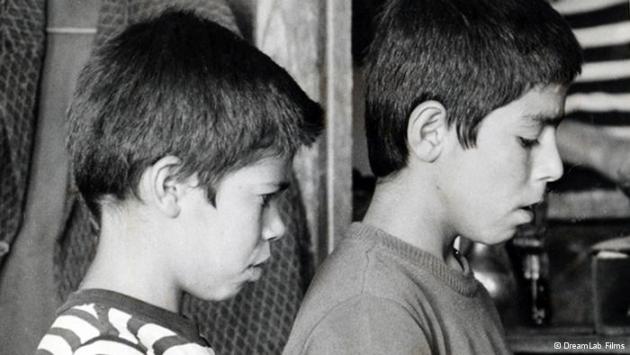

Moving studies: an early work by the well-known Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami was also shown as part of a retrospective. In his film, The Traveller, from 1974, Kiarostami tells the story of a young football fan who wants more than anything to go to Tehran to watch his team play in the stadium. Kiarostami cast amateur actors and children for his film – a typical feature of Iranian cinema. -

Conflicts with the authorities: the film Still Life by director Sohrab Shahid Saless (1974) is another impressive study in the hardships and calamities of ordinary people. Characterised by long, sweeping shots, Saless's film tells the story of a railway signalman in rural Iran. One day, he loses his job, making his already tough life even harder. The film is an indictment of poverty and social misery. -

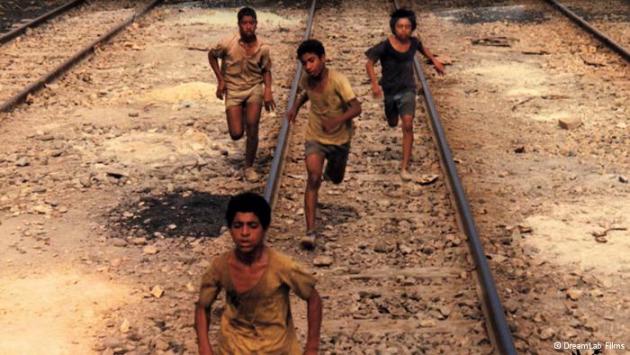

Spotlight on topical social issues: Filmfest Hamburg showed films that were made both during the Shah regime and after it was toppled in 1979. The Runner (1985) by Amir Naderi was the first film to be shown abroad after the Islamic revolution. The film gives the audience an insight into the everyday life of a 13-year-old war orphan in an Iranian harbour city. It is horrifying portrait of poverty and sadness. -

The war with Iraq on screen: in 1986, director Bahram Beyzai decided to make a film about a controversial issue, namely the Iran-Iraq War, which was still being waged at the time. In his film, Bashu, the little stranger, the director tells the story of a ten-year-old boy who loses his family and ends up wandering around the country. Although the Iranian regime initially supported the film financially, when it came to light that the film was going to be critical, the film fell foul of the censors. -

Criticism of the country's precarious economic situation: the film The Need (1991) by Alireza Davood Nejad is an astonishing example of the brutal honesty of Iranian directors when it comes to making films about social reality in their country. In The Need, two young men fight for an apprenticeship. Once again, the cast is young. Here too, the film paints a picture of real life in Iran, a picture that is far removed from national ideologies and propaganda. -

Iranian cinema in Nuremburg: the courage of Iranian filmmakers is not only on show in Hamburg. In Nuremberg too, which is hosting the International Human Rights Film Festival, the focus is on Iran. Films such as Fire under the Ashes highlight the current political climate in Iran. The intention was that Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof would be the festival's patron. Unfortunately, Rasoulof was not able to leave Tehran.

https://qantara.de./en/node/4715

Link

To all image galleries