An unstable situation turns critical

It's four o'clock in the morning when we arrive in Sanaa. Our Houthi escorts give us Yemeni headdresses to wear en route so we don't attract attention. We're a small group of journalists setting off, accompanied by Houthi fighters, on a rather risky journey in an attempt to investigate Yemen's complicated power structures.

The journey to Saada, the Houthi stronghold in the north of the country, takes five hours. For the past few months the Yemeni capital and its environs have been under Houthi control. In the West, the Houthi are generally characterised as Shia Muslims who, like in Iraq, are fighting against Sunni tribes and al-Qaida. The Houthis' activity is, however, considerably more complex.

Dafalah El-Shami is one of our escorts. He's a Houthi leader and a spokesman of the "Ansar Allah" ("Supporters of God"), the Houthis' military wing. He's a friendly, quiet man whom one could more easily imagine as a teacher or a merchant. He tells us that the Houthis are actually Zaidis, followers of a branch of Shia Islam.

"We are all Yemenis"

About ten years ago, the head of the Zaidis, Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi, rebelled against the corrupt government of the former president Ali Abdullah Saleh. Between then and 2010, the government and the Houthis fought a total of six wars. But El-Shami claims that the current struggle is not a denominational religious war. "A great many Sunnis are fighting on our side now. We are all Yemenis," he says.

We stop at a service area about a hundred kilometres from Saada. A poster hangs above the entrance, bearing the inscription "Martyrs". We are told that eight defenceless people were shot and killed in this restaurant by followers of Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, and that after this, the Houthis marched on the capital to drive out al-Qaida. Ahmar had once been an influential politician and businessman, and a long-standing ally of ex-president Ali Abdullah Saleh. However, after the start of the Arab Spring in 2011, the two declared war on each other. According to many reports, it was his men who fired on Saleh's house, seriously wounding the authoritarian ruler, who held power for more than two decades.

Like many cities in Yemen, the metropolis of Saada looks run down and impoverished. Innumerable ruined buildings bear witness to the terrible war that was fought throughout the city. Khat-chewing arms dealers sit in the weapons market in the city centre, selling handguns and Kalashnikovs. Sales of weapons have fallen since the Houthis took Sanaa, one of the arms dealers tells us. It's good for the security situation, but bad for business.

Houthi posters are everywhere in the city, demonising the American government and wishing death to Israel. "The Americans drop bombs on us under the pretext of fighting terrorism, which is not true," says Dafalah El-Shami. "They just want to control the country!" There's hatred for neighbouring Saudi Arabia, too. There has been frequent unrest and violent incursions along Yemen's northern border.

El-Shami leads us through the ruins of Saada. The government did in fact promise to rebuild houses here and set up a fund specifically for this purpose. Nobody here knows where the money actually went.

The Houthis repeatedly speak of the corruption of the regime, and how they themselves have no political views. They've brought down the government and they don't want to be part of the new one, but to control it from outside. Various different groups do in fact support them. Even critical opponents, like members of the General People's Congress, the party of ex-president Saleh, which fought them for many years, are now almost well-disposed towards them. Party spokesman Abdu El-Gindi believes Sanaa has become a great deal safer since the Houthis moved in – and, he says, if they weren't here, al-Qaida would probably have taken the capital long ago.

Yesterday's enemies, today's allies?

It's very difficult to get an overview of the new power structures in Yemen. After brief battles with the government, the army surrendered in September 2014. At the instigation of new leader Abdel Malek El-Houthi, thousands of Houthis had taken to the streets of Sanaa to demonstrate against government corruption, which was said to have got many times worse than during the Saleh era.

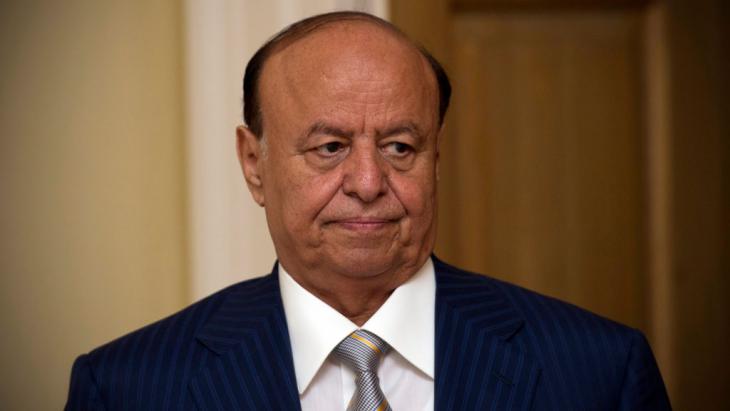

Nevertheless, it remains a mystery how it was possible for Sanaa to fall into their hands so quickly. President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi has spoken of a conspiracy, but rumour has it that he made common cause with the Houthis to get rid of the Islamists and the hated Ahmar, who had previously brought down Saleh. Only the Houthis had sufficient power to drive him out.

The Houthis hate Ahmar, and claim that he represents the Islamists' military wing. He fled abroad after the Houthis seized power, and they took over many of his businesses.

It works in the Houthis' favour that they have until now only ever been in opposition: they weren't involved in forming the new government either. But their opponents don't really trust them. Everyone just wants a piece of the pie, says Shamsan Noaman. He's one of a group of activists who were involved in the 2011 revolution, when the Arab region seemed to be in the throes of democratic change. Today, however, these revolutionaries feel they've been deceived and betrayed by all the political powers. Alongside Ahmar, the Islamists and the Islah party, they are among the biggest losers, not unlike the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.

Who is ruling Yemen?

President Hadi and ex-president Saleh have now fallen out, although they were initially from the same party. The General People's Congress expelled the president from the party, and he responded by blocking their funds. Both Saleh and Hadi are, on the whole, well-disposed towards the Houthis, as they are currently the strongest group in Yemen and are fighting against al-Qaida in the south.

It looks as if the war is going to drag on for a long time. Presidential elections are not on the horizon; the General People's Congress accuses Hadi of not wanting to relinquish power and is demanding new elections. Will Saleh stand again? Definitely not, says his former spokesman Abdu El-Gindi. However, many people see his son Ahmed as a worthy successor.

Yemen seems to be sitting on a powder keg. The situation is highly explosive. After the recent storming of the presidential palace in Yemen, the Houthi rebels demanded that President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi introduce immediate political reforms and threatened serious consequences if he failed to do so.

Faced with these new uncertainties, many Yemenis are nostalgic for the Saleh era. The way they see it, there was greater stability back then than there is today. Tourists don't come to the country any more, either. On top of all this, the south wants to secede: there's fighting in both east and west. For the poorest country in the Arab world, the outlook is not good.

Sherif Abdel Samad

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by Charlotte Collins

NOTE: this article was written before President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi resigned on 22 January 2015