Documenting the tragedy of the Syrian revolt

The horrific news reports from Syria have not let up since 2011. A brutal war is now raging in the country, the media reports regularly on orgies of violence hitting civilians particularly hard, and no end to the suffering seems to be in sight.

The numbers of Syrian refugees have reached shocking levels, with the UNHCR estimating totals at 2.4 million refugees and 6.5 million internally displaced persons. Most of those who have left the country have fled to the neighbouring states of Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, where they often live under extremely difficult conditions. Their tough everyday lives allow barely any scope for processing their traumatic experiences, a situation that is particularly hard for children to deal with. Aid organisations and host countries alike seem hopelessly out of their depth, leaving individuals alone with their problems.

The wish to at least alleviate the situation even slightly was an important motivation for Syrian–British artist couple Nora and Fritz Best to initiate their project "Cutting Away the Void". They set out from their home in Berlin for the Jordanian capital of Amman at the end of 2013 to work with refugees at Dar al Jerha / House of the Syrian Wounded.

Forgetting about life for a while

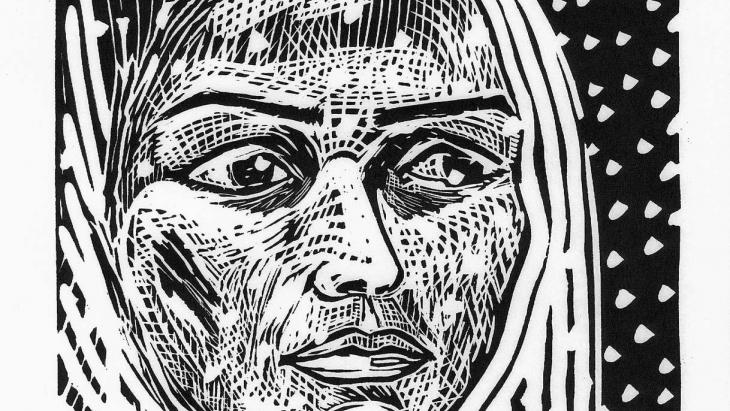

Most of the women and men who live there are severely injured and have an uncertain future. For two weeks, the artists worked with adults in the centre during the mornings, made portraits of them, talked to them and recorded the refugees' personal stories. In the evenings they held linocut workshops for children and anyone else who was interested.

Many Syrian refugee children do not go to school and those who do attend a school are only taught in the afternoons. The staff work double shifts, teaching Jordanian children in the morning and Syrian refugee children later in the day.

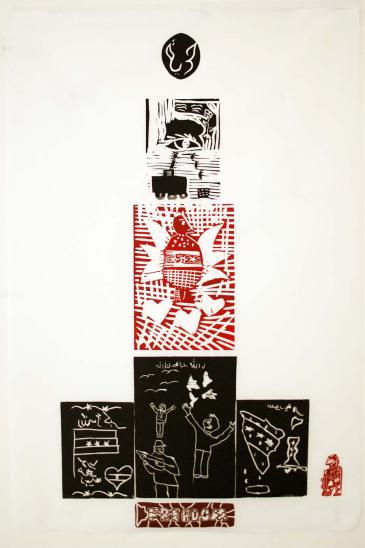

For this reason, the evening art classes were a welcome opportunity for the children to forget their everyday lives for a short time and talk about their experiences. "To begin with, they were very influenced by their parents' revolution rhetoric, but they gradually opened up and began talking about their lives and their dreams," say Nora and Fritz Best.

The pictures the children created tell of the lives they left behind in Syria: the dress still hanging in the wardrobe, the ice creams they used to eat, the trees around their houses, their beloved grandparents. But there are also pictures of weapons and the revolutionary cry for freedom. This strange mixture of simple childlike worlds and big ideals more reminiscent of adult lives makes the Syrian refugee children's pictures both touching and disturbing.

These are the pictures of a generation that was ripped out of childhood too soon and now has to find its way alone in an adults' world, a world in which everyone has massive problems to deal with.

Personal stories of pain and loss

These problems are the subject of the statements made by wounded women and men at Dar al Jerha / House of the Syrian Wounded, which the artists recorded and are on display alongside the portraits. These are stories about the tragedy of the Syrian revolt, which started out as a revolutionary movement of ordinary people and developed into a devastating war that spares no one. They are the stories of women who were badly injured trying to protect their children and now live alone in Amman. They are the stories of young men who joined the armed struggle against Bashar al-Assad's regime, be it out of youthful enthusiasm for a cause or out of naivety, in the belief that the fight would be short and lead straight to a free Syria. Now they are all marked for life, many of them so badly injured that a normal existence is no longer possible.

Nora and Fritz Best have created a series of empathetic portraits. Together with the witness statements, they tell the harrowing story of present-day Syria. The artists focused on two aspects for their project: documentation and processing trauma.

Deliberate choice

They deliberately chose the linocut technique for their project because it starts with a black, negative surface rather than a white one. The picture comes about by cutting away material. In the final print, the cut-away lines appear black and produce the picture.

"We wanted to work with a technique that enables a slow way of working and gives us time to build up a closer relationship and mutual respect with the portrait subjects," says Fritz Best. The subjects in turn were invited to learn the technique, so that the co-operation could develop into a dialogue.

For the project participants, the intensive focus on the artistic technique and the conversations during the workshop had an almost therapeutic effect. It gave them a tool with which they could unearth their stories, confront painful memories and regain a certain amount of self-determination.

The project was concluded with an exhibition showing the works produced in Amman, and with the hope that it can continue. "Cutting Away the Void" is an impressive documentation centring on individuals who are usually overlooked by the media or mentioned only as a grey mass on the margins – the ordinary Syrians with their dreams and suffering.

Charlotte Bank

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire