"These children deserve the same opportunities as children anywhere else"

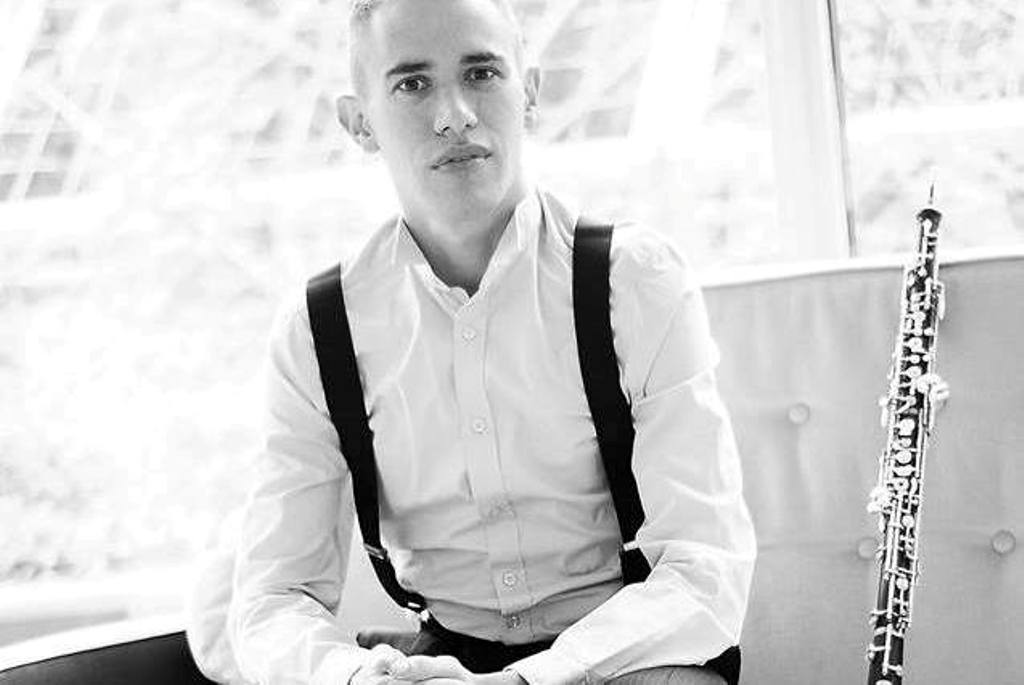

You have recently returned from Kabul, where you taught the oboe at the Afghanistan National Institute of Music. What motivated you to teach in that part of the world?

Demetrios Karamintzas: I previously spent ten years teaching in Palestine, where I worked with Daniel Barenboim and his Barenboim-Said Foundation. When the last war erupted in Gaza, I realised that I was emotionally very involved both in Palestine and in Israel, which brought everything "too close to home". I needed a break, but not from teaching.

A classmate of mine from Julliard, the violinist William Harvey, had been living in Kabul for four years, teaching music full time at the Afghanistan National Institute of Music (ANIM). I decided to join him for the winter term. My reason for going to teach in these conflict zones is that I think that if I won't go, no one else will. These children deserve the same opportunities, the same chances as children anywhere else in the world.

What is the concept behind the Afghanistan National Institute of Music?

Karamintzas: The school was founded by Dr Ahmad Sarmast, an Afghan with a love of music and children, who lived in Australia. He founded the school in 2010 after the Taliban were ejected from Kabul. It is part of the public school system and focuses on music education. The teachers are mostly Afghan, but there are also some international teachers for Western music. The children are just normal kids from Kabul who happen to have a special talent for music.

When I was teaching in Ramallah, I noticed a development similar to the one in Europe: many wealthy families would send their children to learn music. But in Kabul, I didn't get the impression that there are any wealthy families, and it didn't feel at all like an elitist project. There were just regular kids – and by regular I mean quite poor. I know that some of the families are receiving money from the school in order to send their children to school and not to work on the streets.

What were your experiences of teaching music in Afghanistan?

Karamintzas: What I really liked in Kabul – or in Palestine before that – is that I never feel like an overpaid babysitter, which is how I sometimes felt when I was teaching oboe in America. I think that in Afghan society, teachers are highly respected, whereas in Germany or in America, sometimes you get the attitude that "I am paying you, so you are working for me".

In Afghanistan, the children were very, very grateful. Also Western music wasn't very foreign to them since there are some ensembles where Western and Oriental instruments are played together, which I found to be a great way of reaching out not only to the children, but to their families as well.

I want to make one thing clear: I didn't think that my teaching there for such a short period of time was going to change the world for any of them. Of course, I felt it was very important to inspire because, when working with children, you have to keep in mind that this could be the moment that really inspires them. But I really wanted to do something that would last longer, so I launched a campaign to raise money to purchase and donate an oboe: a professional oboe – the first one ever in Afghanistan.

Before that, they only had very old, basic student oboes there. A good instrument is really a game-changer for a student's development. Physically, the oboe is one of the most difficult instruments to play. If, on top of that, you also have to struggle with a faulty or inadequate instrument, it can be doubly frustrating. When talented students have good tools in their hands, they can really take off and make great leaps forward. I brought the oboe and it went to a very talented 12-year-old girl, who could barely restrain herself from practicing nonstop.

In what way did your experiences in Palestine and Kabul differ from each other?

Karamintzas: Life in Palestine is not easy, by any means. But comparing the children in both countries, I would say that the children in Palestine are mainly healthy, somewhat better dressed, most speak at least two languages, and they play real instruments, which we received as donations. There is much more media attention and stronger diplomatic relations with this part of the world than with Afghanistan.

In Palestine there are many guest artists from abroad, thanks largely to Barenboim and his connections. I was very well received in Palestine; I was respected and I am still in contact with many of my students and former colleagues. But in Afghanistan, I felt that they don't get this very often. It was a bit like my early years in Palestine, back in 2004. I felt as if this was the beginning of something.

We should not forget that the situation in Afghanistan is still very extreme: last December, the school was performing a play about suicide bombings that they had prepared at the French Cultural Center. The play was, ironically, attacked by a teenage suicide bomber. One person was killed and several were injured, including the director of the school Dr Ahmad Sarmast, who had to be treated in Australia. It was very traumatic for the children, their families, the faculty and staff as well, and as a result, many of the guest artists from abroad cancelled their trips.

What is funny, on the other hand, is that in both Palestine and in Afghanistan, where you have a completely blank canvas in music education, the oboe is considered to be a "normal" instrument just like the violin, whereas in the West, it is a very rare instrument. Often it is played only by children from wealthier families because it is pretty expensive. In New York, I was the only oboist at my orchestra for a long time, but in Palestine I had eight students!

The school seeks to build society through music. Critics would argue that you need infrastructure first. What do you think?

Karamintzas: I have a clear opinion on that. I have a dog that I love dearly; he comes from the desert outside of Jerusalem. I give my dog shelter and food and safety. But a person is not a dog; people need much more than this. We need culture; we need to feel that we have choices and options; we need to feel that we have free will –in Kabul just like anywhere else in the developing world. Maybe their options are limited; I can't provide every option related to music, but I can provide the option to learn the oboe if a student wants to. I think this is one of the basic elements of humanity, to have free will, to have choices.

I have seen the long-term results over the last ten years in Palestine. I can tell you that such a project literally takes children off the streets. A child who really feels disenfranchised and who feels it doesn't really have a future will very easily turn to something like radical Islam, where he feels he has a purpose.

In Palestine, I have seen it change not only the lives of individuals in great ways; I have also seen it change society. When I started 11 years ago, we had so many problems, especially with the female students. When a girl would reach a certain age, the family would suddenly forbid her to continue taking lessons. Maybe it was because it was Western music or because the teacher was male. So often we would sit in a living room, drinking tea, trying to convince the father that taking music lessons is ok. Now this happens so rarely; it has become normal for people. It's normal to learn music, normal to see someone carrying a violin case on the street, and normal to go to a concert. I have seen a great change and I believe music plays a big part in it.

Ceyda Nurtsch

© Qantara.de 2015