Prince Hamzah – just a storm in the royal Jordan tea-cup?

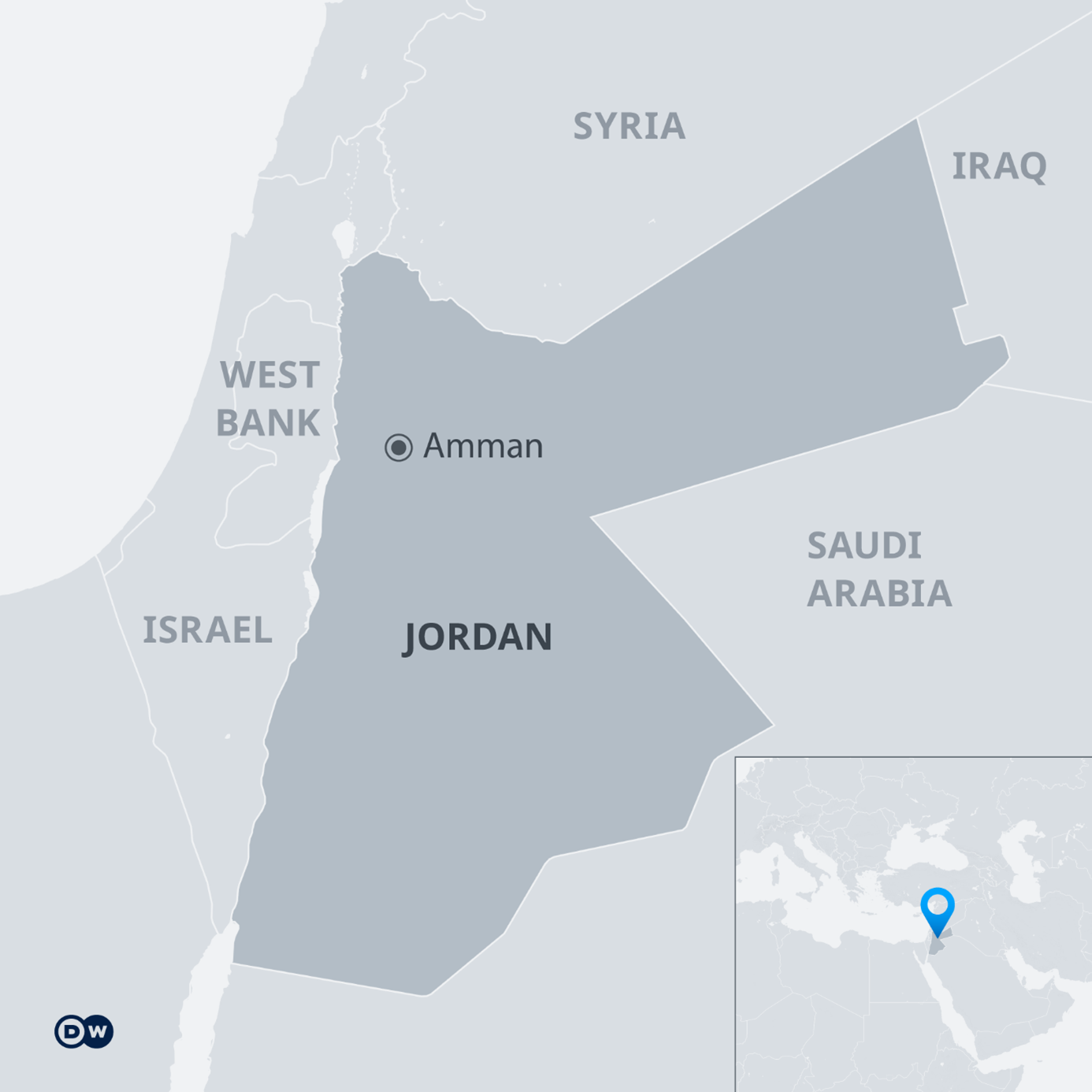

For years, Jordan has been regarded as a stable and peaceful nation, especially when compared with neighbours such as Syria, Palestine, Israel and Iraq. But events last weekend, including news of an alleged plot to overthrow the government – supposedly led by a member of the ruling royal family– seemed to contradict that perception.

Has the world – and particularly Western allies like the U.S. and Germany, who have troops based there and are important financial donors – been wrong about the Middle Eastern state all along?

Despite the view of Jordan as a stable country, public discontent has become increasingly visible in recent years, said Adam Coogle, deputy director of Human Rights Watch's Middle East and North Africa division, which is headquartered in the Jordanian capital, Amman. "It's become increasingly tense here in recent years," he commented. "It's reputation as a sleepy, quiet backwater has been changing."

"Soft dictatorship"

Jordan is best described as a "soft dictatorship", as Yasmina Abouzzohour, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution's Doha Center think tank, writes in an analysis of how Arab monarchies have survived popular protests. Jordan has minimum democracy and reforms come from the top, Abouzzohour points out.

In Jordan, this means the country's king, Abdullah II, may appoint or dismiss the country's prime minister and cabinet ministers, as well as members of the upper house of parliament. Members of the lower house are elected every four years but tend to have comparatively little sway.

This system has been under pressure for decades, but since the so-called Arab Spring in 2011, when popular demonstrations toppled authoritarian regimes, the strain has intensified.

Jordan, too, had its own Arab Spring-style protests. They started in January 2011 and involved a younger generation of more critical Jordanians, known as the Hirak, or popular movement. But, as Abouzzohour points out, most Arab monarchies managed to contain these protests in a similar way: "They granted monetary incentives and limited political concessions … combined with repressive tactics."

In Jordan, this buy-off included promises on subsidies, taxes and wage increases, as well as several changes of government and leadership. There have been 13 prime ministers since the current king took power in 1999 and the move is something that critical Jordanian media outlets have started to describe as a diversionary tactic.

Economic woes driving protests

Still, protests have continued throughout the decade, mostly driven by a deteriorating economic situation, worsening living standards and what are generally seen as broken government promises.

The demonstrations by Jordanian teachers that started in 2019 are a significant example. The government promised teachers a 50% pay rise back in 2014. That pledge was later adjusted before stalling entirely when all public-sector pay increases were frozen in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic. By mid-2020, the Jordanian government had arrested dozens of leading members of the teachers' union and banned the organisation.

"That was a big deal," Adam Coogle of Human Rights Watch explained. "It was the largest independent organisation in the country capable of that kind of mobilisation, and it was closed down almost overnight. It points to a really concerning kind of trend," he concluded.

Other organisations have spotted this trend too. Freedom House, a U.S.-based non-governmental organisation (NGO) that measures how "free" a democracy is, reduced Jordan's ranking from "partly free" in 2020 to "not free" in 2021.

Media freedom watchdog Reporters without Borders also noted that hundreds of local websites have been blocked since Jordan overhauled its media laws in 2012, and underscored the fact that posts on social media are now potentially punishable with jail sentences in the country.

Also noteworthy is the growing number of Jordanian opposition activists agitating for change, via social media, from outside the country. This is something the country has never had to deal with before, locals say.

And although still relatively low, the number of asylum seekers from Jordan has more than doubled in the last five years. In 2015, the UNHCR, the United Nations' refugee agency, registered 1,829 asylum seekers from Jordan. By 2020, that number had risen to 4,955.

Freedom of expression endangered

"Basically, there's growing discontent and frustration, as well as the perception that basic rights are being eroded," said Coogle. "People here feel they cannot express themselves the way they used to." It is in this context that the unusually public scrap between members of the Jordanian royal family may best be seen.

The subject of the weekend's events, Prince Hamzah, half-brother of King Abdullah II and a popular, former contender for the crown, is seen as a reformer and has attended meetings with tribal groups critical of the country's leadership. He's also a canny user of social media.

As one local from Amman who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retribution put it, the video message that Prince Hamzah released to the media complaining of his house arrest, "hit all the right notes. It was as though he'd been listening to people complaining about the government. The things he said were exactly the things you would hear on the street here."

The situation seems to have calmed now. After Prince Hamzah very publicly rejected allegations that he had been trying to undermine the state, he reconfirmed his loyalty to King Abdullah this week.

For ordinary Jordanians, the events remain a mystery. There have been rumours about international conspiracies and security services who went too far trying to stop the popular prince. But the Amman local says people won't discuss it openly. "Everybody is afraid of speaking and afraid of expressing any feelings," the person said. "Most people on Facebook just say things like 'May God protect Jordan.'"

"The country's economy is collapsing and corruption is on the rise," the Amman resident added, "but security is a priority for many. They want to hold onto something and for them the king is their safety valve."

The question being asked now is whether this is just the beginning of a deeper crisis for Jordan, one that could inexorably alter the country's reputation for stability?

"The problem seems to have been solved for now, so I don't believe there is any danger to the stability of the country in the short and medium term," Edmund Ratka, head of the Amman office of Germany's Konrad Adenauer Foundation, commented. "But the fact that the situation escalated this way shows the nervousness of the regime, the potential limits to this style of governance and the tense atmosphere in the country. And in the long term, it is clear Jordan's challenges must be dealt with in a more sustainable way."

Cathrin Schaer

© Deutsche Welle 2021