Keeping it real

Imarhan gives us a taste of the music of the newest generation of Kel Tamasheq musicians. Like nomadic people the world over, the Tamasheq have seen their traditional ways being eroded through lack of living space. As more and more of the Sahara desert, which made up their herding grounds and caravan routes, is lost to pollution, development and political uncertainty, people have been forced to move into cities.

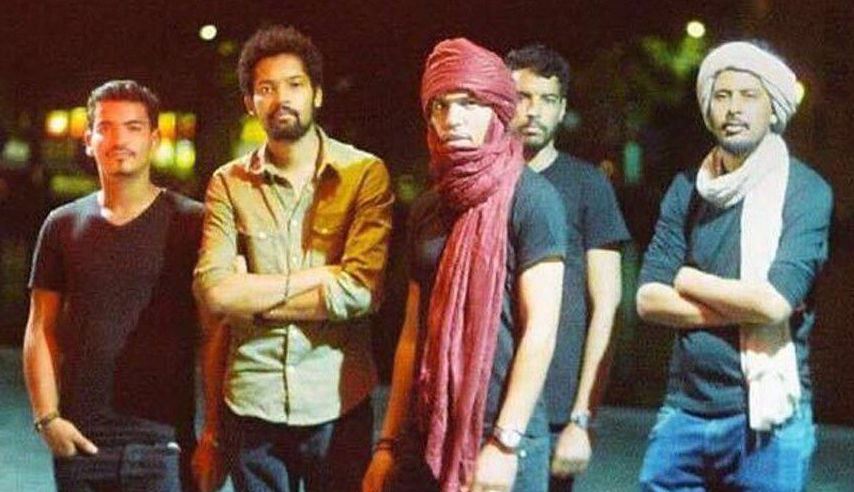

The members of Imarhan live in Tamanrasset in Algeria, near the country's border with northern Mali and traditional Tamasheq territory. As the band has gained international attention, they have assumed more of a leadership role among their generation.

While previous bands focussed on preserving Tamasheq culture and fighting to preserve a way of life, this generation is concerned with both honouring traditions and moving forward and evolving with the times. It's one thing to preserve the past, but it's another thing altogether to keep it relevant to today's world.

Iyad Moussa Ben Abderahmane (aka Sadam) of the band sums it up by saying they know all things come to an end and that everything also evolves. However, they are fighting to preserve their language and it's the music which keeps people connected to it and enables them to continue speaking it. So it only makes sense for them to change the music so that it appeals to a generation of people growing up in an urban environment.

A new sound for a new generation

Joining Sadam in the band are Tahar Khaldi, Hicham Bouhasse, Abdelkader Ourzig and Haiballah Akhamouk. While the six of them might be forging a new sound for their generation, they haven't forgotten the foundations laid down by their predecessors. For while their songs have expanded beyond the nuts and bolts of the almost trance-inducing guitar and rhythm of bands like Tinariwen, desert blues guitar still remains central to their sound.

Yet, from the opening track of Temet (released by City Slang Records) you know you're in for a different experience. "Azzaman" sets a blistering pace with its funk-influenced rhythms and searing guitar work. Perhaps if Jimi Hendrix had sat in with Sly and the Family Stone or Led Zeppelin had been a bit more influenced by James Brown, we'd have heard something similar before. However, what it reminded me of most was some of the inner-city, African-American groups – think The Chambers Brothers – of the late 1960s and early 1970s. There's a hard gritty edge to the soulfulness that's reflective of life among concrete and survival in a cityscape.

This is quite the contrast to the swooping melodies and hypnotic beats of some of the other bands and it could leave listeners a little disconcerted. However, as the album progresses we see how they have done an impeccable job of incorporating the old with new. In fact, in songs such as the album's final track, "Mas S-abok", they show they are every bit as capable of playing beautiful acoustic music as rocking funk.

The art of graft

What's most fascinating is hearing how well they've managed to blend the traditional and new together on some of the songs. The second track on the disc, "Tamudre", is a great example of this. The guitar work continues to lay down some of the same funk-influenced rhythms of the opening song, but this piece also includes the ensemble vocal work and hand-clap type percussion of older songs.

Even more remarkable is how seamlessly they've been able to accomplish this. Never once does it feel like the band has grafted two separate things together. It feels like there has been an organic progression which has allowed the musical styles to meld so they form something new. While they have maintained the sound of the desert blues we've all come to associate with Tamasheq musicians, they have also given us something more.

What's even more impressive is how they've managed to sustain the core of emotional commitment which has given Tamasheq music its passion and integrity. No matter if Imarhan are playing something like the disco influenced "Ehad Wa Dagh", the incredibly funky "Tumast", or the haunting "Tarha-nam", they sound as if they're still trying to instil the same sense of dignity and pride in their listeners as any of the bands who came before them.

A responsibility to ʹconnectʹ

The young men of Imarhan havenʹt faced the same fights as their predecessors. They didn't lay down guns and pick up guitars after the rebellions of the 1990s. However, they have inherited the same feeling of responsibility to their people – a responsibility involving finding a way to preserve their language and whatever aspects of their culture they need to help them retain their awareness of their place in the world.

In the Tamasheq language ʹtemetʹ means connections and the album is all about trying to create connections. Connections between a young and urban population and their culture and why its important. However, it's also about maintaining connections with the wider world and reminding them the Kel Tamasheq still exist and are still fighting.

Imarhan's latest album Temet is a testament to not only their musicianship and skill, but also to their intelligence. Rather than the safe option of following directly in someone else's footsteps, they've forged their own path and created some great music in the process.

Richard Marcus

© Qantara.de 2018