Peddling high-brow Islamophobia

As I was approaching my neighbourhood shopping street the day before the European election, I was struck by a large truck bearing German flags and logos for the far right-wing party, Alternative fur Deutschland (Alternative for Germany), or AfD, but also by a large reproduction of an oil painting. It featured some swarthy, sinister-looking robed men sizing up an enslaved, lighter-skinned woman and was accompanied by the slogan: "Europeans vote AfD … So Europe doesn't become Eurabia!"

Eurabia is an Islamophobic term used in connection with a conspiracy theory positing that Muslim people will soon overrun Europe – a theory pushed by Norwegian extreme-right terrorist Anders Breivik, who murdered 77 people in 2011.

Intentional recourse to popular cultural memory

The poster – one of several from the AfD's "Learning from Europe's history" campaign that re-interpreted famous artworks to push a xenophobic agenda during the EU election – features "The Slave Market" (1866) by French painter Jean-Leon Gerome, an Orientalist work that itself has been judged to present racist tropes from colonial times.

The same image was also used to remind voters of what happened in Cologne during New Year's Eve in 2015, where hundreds of sexual assaults were attributed to men of "North African" appearance.

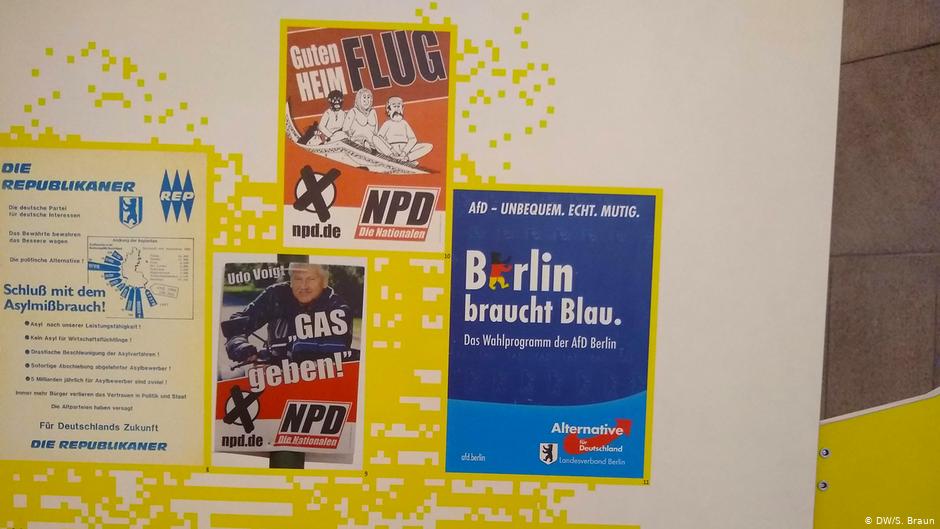

Just as the AfD refused to take down the poster after requests from the owners of the original work, party activists have been trying to censor cultural institutions. The party recently pressured the organisers of the exhibition titled "Immer wieder? Extreme Rechte und Gegenwehr in Berlin seit 1945" (Again and again? The extreme right and resistance in Berlin since 1945) at Berlin's Rathaus Neukolln (Neukolln Town Hall) to remove content related to the party during the elections to the European parliament.

"We want to use the exhibition to draw attention to the continuities of the extreme right in Berlin and at the same time to point out facets of social resistance," said Vera Henssler of the "Antifaschistisches Pressearchiv und Bildungszentrum" (Antifascist Press Archive and Education Centre) in an interview. "The AfD is only a small part in this story, but it is unquestionably one of the actors."

The AfD-related exhibition material mentions, for example, how party members joined neo-Nazis on the streets in anti-"Islamisation" protests during the peak of the migrant crisis in 2014 and 2015. It also traces how right-wing elements have gained ground within the AfD – initially an anti-EU party – and made Islamophobia a central platform.

After the election, the removed panels were restored to the exhibition. In reaction, the party says it will seek a court order to have them removed, calling the exhibition organisers a "left hate" organisation and adding that since they receive government funds, they should be neutral and uncritical: "We will not tolerate this in public spaces with public funds," said AfD Berlin party spokesperson Ronald Glaser.

Freedom of expression?

The AfD has sought to censor cultural and educational institutions on a number of occasions. It sued the Berlin Social Science Centre (WZB) over a study on the "Parliamentary Practice of the AfD in German State Parliaments", declaring that it violated their "personality rights." But in April, a court declared the study valid and in accordance with the right to academic freedom and freedom of speech.Even what constitutes free speech seems to be a matter of dispute, however. The AfD has also been twisting the rhetoric of freedom of speech to their own advantage – with Ronald Glaser for example commenting that "the restoration of freedom of expression is one of the main concerns of the AfD."

Another prominent incident is a criminal investigation of the "Zentrum fur Politische Schonheit" (Centre for Political Beauty) over its building of a Holocaust memorial replica on land next to the home of Thuringian AfD leader Bjorn Hocke.

After the artwork was installed in 2017, Hocke called the artists' group "a criminal organisation, even a terrorist organisation", during a speech delivered alongside far-right leaders such as Lutz Bachmann, founder of PEGIDA (Patriot Europeans Against the Islamisation of the Occident) and Austrian Identitarian Movement leader Martin Sellner.

The latter infamously received a donation from the Australian terrorist who attacked a mosque in New Zealand.

The case was recently dropped after it was revealed that the state prosecutor running the investigation donated a small amount of money to the AfD.

Right-wing offensive on Germanyʹs cultural institutions ?

But Kai Arzheimer, professor of politics at the Institute for Political Science in Mainz, believes that efforts to influence cultural institutions are part of a "worrying" trend that strikes at the heart of freedom of expression.

"It also fits with their manifesto for the election in Saxony calling for funding cuts that would affect organisations incompatible with the AfD's world view," he said, referring to the party's growing strength in a state where it beat the major parties at the recent European election.

"This modern far right have transitioned to paying a lot of attention to cultural spaces and to knowledge-producing institutions," Cynthia Miller-Idriss, professor of education and sociology at American University in Washington D.C., commented.

Her book "The Extreme Gone Mainstream: Commercialisation and Far Right Youth Culture in Germany" examines the increasing intersection between mass fashion and music culture and a more socially integrated far-right scene that is no longer marked by shaved heads and bomber jackets and that actively renounces neo-Nazi associations.

"What is new is not the strategy," says Julian Gopffarth, a researcher at the European Institute of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Gopffarth revealed that while the German New Right has been seeking greater "cultural hegemony" since the 1970s, these efforts had limited impact until recently. "With the rise of the AfD, the far right has actually reached positions of power from where this strategy can be implemented in an unprecedented way," he added.

The AfD itself admits to taking on a new high culture strategy. "The use of historical images for an election campaign was something new," is how Ronald Glaser explains the AfD's "Learning from Europe's history" campaign. Referring to the use of The Slave Market, he added, "We did it because the picture shows clearly where a multicultural society could lead."

High brow Islamophobia

Gopffarth calls this a form of "high-brow racism" that continues "an elitist understanding of European civilisation as superior, that was the norm in colonialism" and resonates with many AfD supporters. "Using this image allows the AfD to link old far-right tropes to a new, more educated bourgeois audience that rejects Islam," he added.

Cynthia Miller-Idriss finds that views about the superiority of European civilisation as conveyed in high art are also to be found in narratives of the American Alt Right. Both, she says, share "an Islamophobic and anti-immigrant, fear-mongering agenda" while seeking legitimisation as reasonable, educated citizens who appreciate culture and are "different from the racist skinheads."

But the AfD's Islamophobic narrative, in addition to its perceived attacks on cultural institutions, has inspired a sustained backlash. "They use art in a political sense, but they don't want art that is political," says Raul Walch of "Die Vielen" (The Many), a Germany-wide artists' collective that initially helped bring around 10,000 people to the streets of Berlin in May 2018 to protest against an AfD rally.

"Freedom of speech and freedom of artistic expression are very closely linked," he said, one week after another artist-led protest against the far-right saw around 28,000 gather across Germany. It seems this culture war is only just getting started.

Stuart Braun

© Deutsche Welle 2019