Against all the odds

Christy Garland, unlike most of the politically committed filmmakers who travel to the region, knew very little about the conflicts in the Middle East when she arrived in Palestine for the first time.

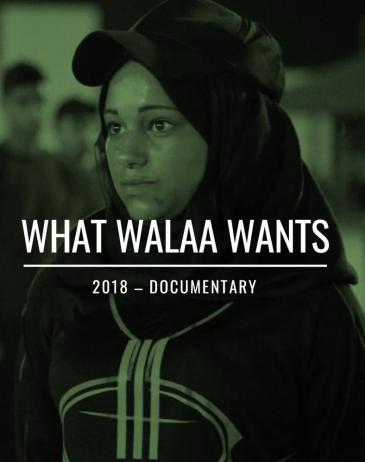

Actually, her first visit had a completely different purpose – workshops for teenagers interested in designing computer games. Though initially she had no intention of making a film about it, a chance meeting with a 15-year-old girl by the name of Walaa in the Balata refugee camp near Nablus proved so memorable that Garland decided to document her story.

Already at that time, Walaa had a surprising wish: she was determined to join the Palestinian security forces. Over a period of five years, Garland travelled regularly to Palestine – for several weeks at a time – to follow Walaa's story. Walaa herself was less enthusiastic about the constant attentions of the camera.

Garland's persistence over long periods at the refugee camp, however, eventually paid dividends, gaining her the trust of both the young woman and her family. The resulting film provides privileged glimpses of a world most of us know very little about, or at best catch only fleeting glimpses of from afar. "In my documentaries, I like to explore the world through the eyes of my protagonists," Garland explains.

The director has a penchant for the offbeat story: her film "The bastard sings the sweetest song" portrays a son's relationship with his ageing mother in Guyana. "Cheer up" explores the sad souls of a team of Finnish cheerleaders.

Challenging circumstances

In Balata refugee camp the walls are plastered with portraits of "martyrs", colourful posters of young men, many in martial poses, proudly brandishing weapons. Some carried out attacks; others were killed by the Israeli army. Making a film in such an environment is challenging, not least because the willingness to try to understand a situation can all too easily be interpreted as a readiness to be in sympathy with it. Christy Garland, however, is an observer, never judgemental, she neither condones nor condemns.

When Garland began filming in 2012, Walaa's mother Latifa had just returned to her family after years in Israeli prison. She had been arrested for supporting a suicide bomber in a failed attempt to enter Israel. In 2011 she was freed in a prisoner exchange deal for Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, who had been kidnapped by Hamas in Gaza – Walaa was just 15 years old at the time.

Having members of one's family in prison is the rule rather than the exception in Palestinian society – a phenomenon particularly prevalent among families in the refugee camp. Not that they are all criminals, of course, but because under Israeli military occupation in the West Bank, involvement in political activity, demonstrations or posting critical material on social media can all bring detention.

A traumatised society

According to figures released by human rights organisation "Addameer", more than 6000 political detainees are currently being held in Israeli prisons, 450 of those in so-called administrative detention, which allows prisoners to be detained without charge or trial for an indefinite period. "Addameer" estimates that more than 800,000 Palestinians have been in Israeli custody since 1967.

It is a situation that has scarred Palestinian society. In Walaa's family too, her mother's long absence and the knowledge of her traumatic experiences in prison have left their mark. Is she proud of the time her mother spent in an Israeli prison, Walaa is asked. "Not always," she replies.

In the refugee camp, prison is not only considered normal, it is also something of a badge of honour. This is not a view shared by Walaa, however. She is very much her own person and has decided she wants to join the "Sulta", the Arabic name for the Palestinian Authority (PA). It is a wish she is determined to fulfil, no matter what others may say or how absurd they find the idea. In the conservative Balata refugee camp, the PA is not highly regarded and the work is seen as poorly paid.

Walaa's brother is particularly hostile towards her decision. He prefers direct confrontation with the Israeli occupier. When he was arrested and put before a military tribunal, Walaa was devastated. During the trial she tried to rush towards her brother and was arrested by Israeli security forces. The episode led to her spending two weeks in prison.

Prison talk

Hardly surprising then that ill-treatment in prison is the main topic of conversation whenever the family gets together. The collective trauma caused by exposure to violence in Israeli prisons was brilliantly captured by Raed Andoni in his 2017 Berlinale film "Ghost Hunting", which won the prize for best documentary.

What Walaa wants, her great dream, surprisingly, is the PA, the veteran Palestinian autonomy authority, established in 1994 as an outcome of the Oslo peace process and then headed by Yasser Arafat. Initially intended as an interim governing body, it was supposed to be absorbed into an independent Palestinian state within five years. Twenty-five years on, that dream appears more remote than ever.

Even though Palestine now exists as a de-facto state at the United Nations, the authority controls security only in the Palestinian cities, most of the West Bank remains occupied by the Israeli army. Among the Palestinian population, the PA is seen as corrupt and powerless, its political leadership as outdated and devoid of ideas. Nevertheless, with 160,000 employees, it is the most important provider in the Palestinian territories.

Escaping instability, unemployment and camp mentality

It is the young Palestinians in particular who have long protested against the Authority. Its cooperation with the Israeli army on security issues has been an especial bone of contention and led to accusations of collaboration with occupying forces. But Walaa, who grew up in the Balata refugee camp near Nablus, sees things differently. Through service with the Palestinian police force, she sees an opportunity to contribute towards the construction of a state which does not yet exist.

To her, the Authority also represents a chance of escape; escape from uncertainty and instability, from unemployment and from the hero worship accorded the young men who choose to fight against Israeli occupation. It also offers release from the fixed and conservative attitudes to gender in the refugee camp. In these terms, her intention of working for the Palestinian police can also be seen as an act of emancipation.

Emancipation, perhaps, but it landed her in a PA boot camp in Jericho in 2015. When she arrived there, Walaa found it all very different to what she had imagined. Neither the crawling through the dust nor the unquestioning obedience of orders was to her taste. It was only after her superiors began to have more confidence in her and to give her a greater degree of responsibility, that she finally began to relish her new life.

At the end of the film, Walaa has completed her training and sits as a duty officer at the desk of a police station. She took special leave from her job with the Palestinian police in Ramallah to attend the Berlinale screening. Qantara.de asked Walaa whether her objectives might not be better served by becoming a politician. "Why not", she joked, "maybe I'll become a minister."

Garland's film allows us an intimate insight into the life and motivations of her protagonist. The result is a straightforward and unbiased film that is likely to prove politically controversial.

The PA may want to appropriate it and many Israeli viewers will be just as disappointed by it as the critics of the Palestinian government. And that is probably the biggest compliment that can be paid to a documentary that so steadfastly refuses to indulge in clichés or to patronise either its audiences or its protagonists.

Rene Wildangel

© Qantara.de 2018

Translated from the German by Ron Walker