Football, film and freedom in Sudan

This is certainly not the first time that the Berlinale has featured a film about football as a gauge of how liberal a society is. There have in the past been several such films, most of which focussed on Iran, where women have long been fighting to be able to live out their passion for football by either playing the game or watching professional matches in stadia.

While the official line is that this is still not to be encouraged, it was made possible for the first time in decades in 2018. The documentary "Football under Cover", which focussed on the Iranian women's national football team, was shown at the Berlinale in 2008, while Jafar Panahi's film "Offside", which introduced the world to the Iranian women who opposed the ban on women in stadiums was a hit at the Berlinale in 2006.

But unlike Iran, Sudan does not have the reputation of being a football nation. Its men's team ranks 127th in the world, right behind the Caribbean nation of Antigua and Barbuda. In recent years, Sudan has been making headlines for the genocide in Darfur and the Nuba Mountains, the persecution of opposition politicians and activists, the independence of South Sudan (164th in the world football rankings) and the ongoing civil war rather than for its prowess on the football field.

Women deprived of rights by law

It goes without saying that all of this has had little impact on the Sudanese passion for football: national league games still sell out and the popular rivalry between FC Barcelona and Real Madrid is celebrated throughout the region. But the world of football in Sudan is almost exclusively male; women are not wanted.

A quote included in the film's opening credits sets the scene: women in Sudan are allowed to neither make films nor play football under Islamic rule.

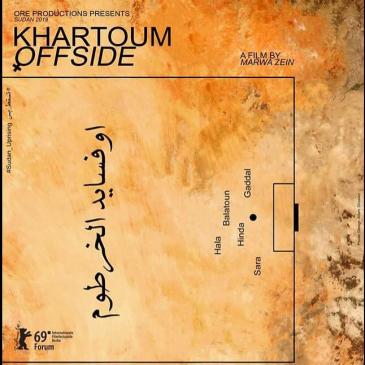

Director Marwa Zein's documentary "Khartoum Offside" is all about a group of courageous women who are rebelling against marginalisation.

This marginalisation is the result of a law known as the "Public Order Act" that was passed by the Islamist government and systematically persecutes women. "Immoral behaviour" is punishable by imprisonment or up to 40 lashes.

"Immoral behaviour" can be anything: wearing trousers, smoking, drinking or playing football.

"People in Sudan – especially women – are fed up with this despotism. This is why they are taking to the streets to protest," says Marwa Zein, who laments the fact that this struggle is being virtually ignored by the international community.Since the start of the Sudanese mass protests against the government in December 2017, hundreds of people have been arrested and dozens killed by the security forces. According to Zein, the international media is remaining silent and there is no political pressure.

Zein says that for her personally, it was not easy to make this film. She originally planned to make a five-minute short film about women's football for a women's rights organisation, but she was so fascinated by the subject that she spent three years working on it. "Throughout all that time, I never once got a permit to film. I couldn't even buy one," she adds, referring to the rampant corruption in Sudan, which ranks 172nd of 180 countries in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index.

To make matters even more difficult, there is no infrastructure for film funding or support in Sudan. It is a pity, especially as Zein is a successful young women, who graduated from film school in Cairo and has worked with well-known Arab directors. She would be a real poster child for her country.

Instead, she is a thorn in the side of the Sudanese government, as are the protagonists in her film, Sara and her fellow campaigners, who are fighting for their rights as women footballers. They are certainly talented and would love to both play in a national league and test themselves in international tournaments.

A young generation rises up

The FIFA Women's World Cup will take place in France this year. But to get there, these Sudanese footballers would have to do more than just qualify on the pitch. They would also have to overcome the obvious corruption they are fighting. After all, there is enough money coming from FIFA to support women's football in Sudan.

But apart from making regular promises, the men of the Sudan Football Association do nothing. "You need a league with eight teams," they say, but the setting up of a league has been prohibited in a ruling by the country's most senior Islamic legal scholars. The players had hoped that elections in the Sudan Football Association would bring about some change, but to their dismay, the same people are voted in again and again.

These confident young women reject the rigid policies of the government, which systematically deprive women of their rights. They make fun of the autocratic laws and the corrupt rule of the old men in Sudan.

Sara dreams of reviving a bar in Khartoum that her family ran in South Sudan until the turmoil of the Second World War. But this plan too stumbles at the hurdle of rampant corruption. And her plan to serve local beer in her bar is even more of a distant dream.

"These women are incredibly courageous," says Marwa Zein. "They want to overcome the system and they truly believe in their own power." With her film, she also wants to change the cliche-ridden perception of Sudan and help overcome the country's political misery.

She would love to screen her film in Sudan, "in the places where I filmed. But also in the west, in Darfur, in the Nuba Mountains." There are certainly enough young people who want to see change. This is borne out by the most recent protests in country.

Rene Wildangel

© Qantara.de 2019

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan