″Bombs pass and we bark″

The July War began on 12 July 2006, two days before Kerbaj started his blog on the conflict. That′s when Hezbollah forces in southern Lebanon crossed into Israel, killed three soldiers and kidnapped two others. Israel retaliated not just against Hezbollah forces, but with a ″bang″: by bombing bridges, buildings and other targets across Lebanon, including the country′s main airport. Accounts differ on how many Lebanese civilians died during the war – there is general agreement that 44 Israeli civilians were killed – but Kerbaj dedicates Beirut Won′t Cry to ″1187 numbered boxes.″

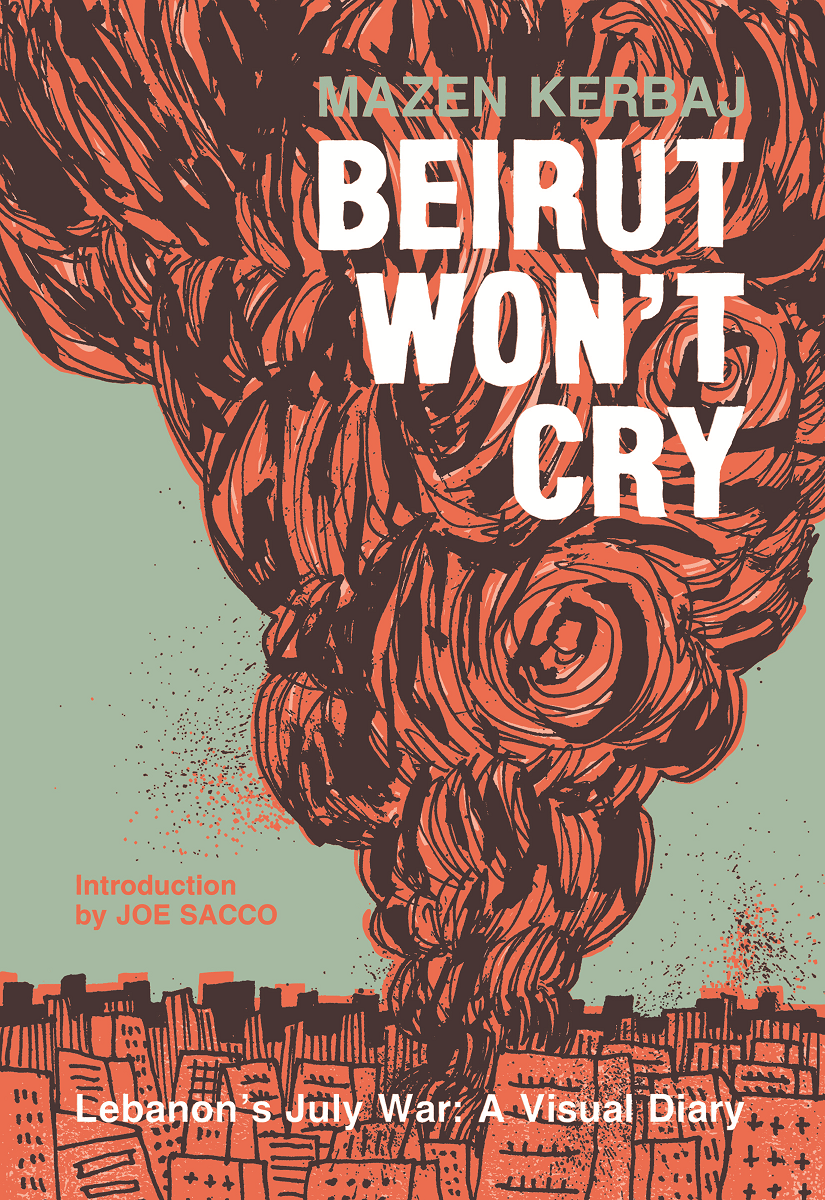

The book faithfully reproduces Kerbaj′s wartime blog, down to its grammatical and spelling infelicities. Although it′s image-centred, at times there are clusters of text-only pages, mostly when Kerbaj couldn′t get a strong Internet connection. Throughout the book, each of his single-panel drawings bristles with the angry, anxious and loud creativity of those six weeks. While the blog texts were written in English, the drawings′ text moves fluidly between in English, Arabic and French.

As acclaimed graphic novelist Joe Sacco writes in his introduction, the book was produced ″in extremis, under the bombs. Mazen [Kerbaj] did not know what tomorrow or the next hour had in store whenever he took the pen to hand.″

Even though readers in 2017 know how the war turned out, the book maintains the blog′s day-to-day urgency. Combined with this urgency, the eleven-year distance gives the book a somewhat helpless feel: we′re reading a call to action – and a plea to share Kerbaj′s message – more than a decade too late.

All the translation is Kerbaj′s own work. Although he has previously published more than a dozen graphic novels, mostly in French – including a French version of this book – this is Kerbaj′s long-awaited English debut.

Art versus war

On 19 July, a week into the bombardment, Kerbaj sketched a self-portrait. He is shown drawn in dark, sharp lines, emerging from an enlarged, misshapen window. Here, the artist-author is holding a pen high in his unnaturally thin, elongated arm.

Above him, alongside giant stars, two planes fly in close formation. The man, dark bags weighing down his eyes, shouts from his window: ″Come down you cowards! I′ll kill you all with my pen!″

Yet, lest this image be taken too seriously, a faceless voice issues from the dark window below: ″Shut up.″

This attempt to fight back, both earnest and self-critical, shifts throughout the book. In several of his posts, Kerbaj calls on his readers to raise awareness, urging them to share the story of Lebanon′s suffering. Yet at other times, Kerbaj seems to doubt his project, scolding himself for worrying about his art in a moment when children are being bombed.

Two days after Kerbaj′s self-portrait as a man threatening air bombardment with his pen, Kerbaj depicts himself in a strikingly different manner and this time the text is in French. Instead of a man, the artist is now an anthropomorphised dog, with the same heavy black rings under his eyes.

Here, the artist has no words, nor a pen, nor a hand with which to wield it. He gives an inhuman howl as the text behind him reads ″les bombes passent et nous aboyons,″ or, ″Bombs pass and we bark.″

An image on 27 July shows yet another attitude toward the bombardment. In this self-portrait, we don′t see the artist at all. Anthropomorphic planes roam in a circle over the artist′s building and two speech bubbles emerge from a window in Arabic, telling us that as the Israeli air force circles above, the author is going to sleep.

Throughout, the narrative shifts wildly between a feeling of purpose, powerlessness and a desire to eat or sleep. On 10 August, a dark-faced and armless self-portrait declares, in Lebanese Arabic, ″I don′t know what I should do.″

On the same day, there are other drawings – done jointly by Kerbaj and his five-year-old son Evan – of the two sitting together at Kerbaj′s favourite cafe-bar. While Kerbaj drinks a coffee, Evan drinks a strawberry juice. Another of Evan′s drawings depicts a eerily frightening ″patapouf″.

Family in wartime

Throughout Kerbaj′s memoir, we see glimpses of his parents, his ex-wife, his girlfriend and his son, Evan. Most urgently, Kerbaj must face questions about Evan′s safety and well-being.

The memoir both echoes and contrasts Atef Abu Saif′s chronicle of the Israeli bombardment of Gaza in the summer of 2014, The Drone Eats With Me. In both memoirs, fathers worry about their children. Yet Kerbaj′s range of options is entirely different. Unlike Abu Saif, Kerbaj could′ve fled the country. His French ex-wife and his son almost did.

But Kerbaj doesn′t want to leave his city. In the end, Evan stays up in the mountains with his mother, while down below, Beirut is being bombed. Kerbaj worries about children, but often his worry is focused on the Lebanese children in the south who have died in bombings and fire.

We hear briefly about Kerbaj′s father and siblings. But there′s much more about Kerbaj′s mother, the artist Laure Ghorayeb, who also drew for her own blog, which was ultimately collected into a book titled 33 Jours. Kerbaj also counts fellow artists and musicians among his ragtag family.

Ultimately, Kerbaj is much closer to the Western reader′s position than is Abu Saif. Kerbaj has a relative mobility and finds himself both inside and outside the conflict, with choices to make about how to position himself and his message.

At the end of this book, Kerbaj tells us he′s going on a 10-day tour of Sweden and Norway. ″Normal″ life is about to resume for Kerbaj, just as it will for the reader as soon as we close the book. The author reminds himself that he′s a musician who must pack his things and clean his trumpet. The last sentence is: ″Until?″

Maintaining the blog in this way – with no afterword, no update about what′s happened to Lebanon in the years since – gives us an unsatisfying, un-stage-managed ending. Yet it also feels startlingly real: with mingled relief, uncertainty and free-floating worry about the future.

Marcia Lynx Qualey

© Qantara.de 2017