Jewish Orientalism?

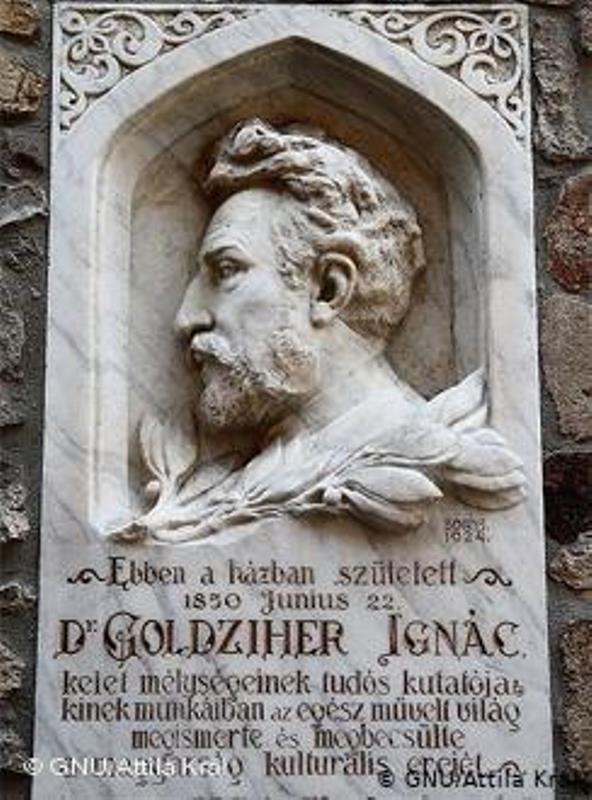

"Surrounded by thousands of worshippers, I rubbed my forehead on the floor of the mosque. Never in my life was I more devout, more truly devout, than on that sublime Friday," wrote Ignac Goldziher (1850–1921) in his diary after attending Friday prayers in a Cairo mosque.

For the American scholar of Jewish Studies Susannah Heschel, Goldziher is more than just one of the most eminent scholars of Islam that Europe has ever known. He stands alongside a line of Jewish-German academics of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, whose curiosity and fascination led them to forge familial links between their religion and Islam.

In the book "Juedischer Islam" (Jewish Islam), which has only been published in German translation, Heschel shines a light on a Jewish–Islamic symbiosis that seeks to reshape the image of the Modern Age from a perspective other than the Christian view of the world.

This impressive story begins with Abraham Geiger (1810–1874). In his 1833 essay "Was hat Mohammed aus dem Judenthume aufgenommen?" (What did Mohammed take from Judaism?), Geiger, one of the fathers of Reform Judaism, for the first time drew attention to parallels between Judaism and Islam.

Geiger came across sentences from the Mishnah or the Midrash in the Koran. The similarities between the religious scriptures and doctrines captivated him. "The genesis of Islam reveals to us a piece of Jewish history that would otherwise have remained completely hidden from us", wrote the renowned rabbi.

But, as Heschel makes clear in her compact collection of biographies, Geiger was not an exception to the rule. Shlomo Dov Goitein (1900–1985), Arabist and Orientalist, even went as far as to refer to Islam as "Judaism in Arab form".

Like him, others also used Islam as a kind of template for looking at their own religion from a new perspective. Heschel shows how by moving closer to Islam as a religion that is comparable with Judaism in its strictly monotheistic teachings and image-free traditions, Jewish thinkers and academics were simultaneously able to carry the polemic against Christianity and its doctrine of the Trinity to extremes.

Fascinated by Islam

Some of them even converted to Islam. One such a convert was the well-known journalist and author Leopold Weiss (1900–1992), who was also known as Muhammad Asad. Another was the philosopher and writer Hugo "Hamid" Marcus (1880–1966), who was deported to Sachsenhausen in 1938. Muhammad Abdullah, the imam at the mosque in Berlin-Wilmersdorf, campaigned for his release and helped him escape to Switzerland.

Heschel concludes that whether they converted or studied the religion academically, German Jews were fascinated by Islam. The appropriation of Islam was, according to Heschel, at the same time a mirror image of a Jewish attempt to position itself in the world with all the ambivalence of this process. Heschel assumes that Jewish scholars of Islam broke through the dualism between Europe and the "Orient": "They belonged to the colonised Others and were, at the same time, part of European imperialism."

This is why Heschel doesn't hesitate to list the negative effects of a perspective that disputed the independence of Islam, re-defining it as the archive of one's own history. In particular, she warns against concealing negative images; after all, not all of these academics saw Islam in a positive light. Heinrich Graetz (1817–1891), for example, saw Islam as another great enemy of the Jews. For his part, Salomon Formstecher (1808–1889) considered Islam despotic.

For Heschel, Eugen Mittwoch (1876–1942), professor at the Seminar fuer Orientalische Sprachen (Department of Oriental languages) and director of the Nachrichtenstelle fuer den Orient (Intelligence Bureau for the East) is a "prime example of a Jewish scholar who on the one hand emphasised the Jewish origins of Islam and on the other, put himself at the service of Germany's colonial interests".

The "Orient" – a screen on which to project fantasies and longing

Nevertheless, overall, these aspects are overshadowed by a largely romantic version of history that at times gives the impression of being apologetic. The reference to the "complex motivations and objectives of the Orientalists" qualifies the dominance characteristics of the far-reaching phenomenon that Edward W. Said, co-founder of the theory of post-colonialism, called Orientalism. In Orientalism, images of brutality, primitiveness, exoticism and inadequacy merge and create hierarchies.

When Heschel writes that "Jewish scholars never saw their academic discipline as a 'decisive attack' on the Koran and the Islamic faith", she is simplifying a complicated context in order to produce a totally positive narrative. Things become problematic in particular when Heschel laments that Muslims never positioned themselves in relation to Judaism in a comparable way.

Artificial dualism?

This is a daring theory. On the one hand, she neglects to see Jewish references in Muslim scriptures and traditions as evidence of Muslims positioning their religion in this way. On the other, she does not do justice to the lived Muslim diversity in its relations with other groups – however banal they may be – also relations that are far removed from the world of academia. An assumption such as this, can lead to a new, artificial dualism: on the one side, Jewish respect for and fascination with Islam; on the other, however, nothing but a lack of Muslim interest in Judaism.

In addition, the book overlooks the special role played by Arab Jews (also known as Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews), in this whole constellation. While Heschel briefly mentions that in Geiger's opinion, Arab Jews were not exactly learned, this statement of supposed facts goes uncommented. Heschel fails on a number of occasions to make any critical reflections on the Orientalist knowledge of Ashkenazi Jews' imperial view of and discrimination against Arab Jews.

Here too, the "Orient" becomes a surface on which to project fantasies and yearnings, inequality and power. Heschel's "Juedischer Islam" is part of a multi-faceted narrative in which being Jewish, being Muslim, being European, and being Arab are not natural opposites, but are interwoven in the most profound way. For this reason, as Georges Khalil notes in his wonderful afterword, all the more attention should be paid to the figure of the Arab Jew and the related negotiations of self-determination and identity.

Ozan Keskinkilic

© Qantara.de 2019

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan