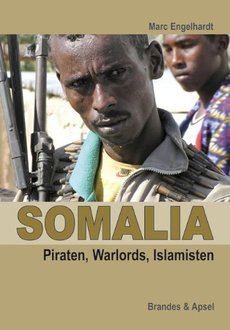

Pirates, Warlords, and Islamists

Somalia remains something of a sealed book for most people. After more than 20 years without a government, the country has been left to wallow in the depths of anarchy and violence. It is a country of nomads, in which clan affiliation is still far more important than the rule of law. Regarded as a breeding ground for militant Islamism, the homeport of piracy, and a crisis zone of catastrophic famine, is it possible for this country to ever have a viable future?

From 2004 to 2010, during his time in Kenya as a correspondent on Africa, Marc Engelhardt visited Somalia a number of times and managed to get an idea about the situation in the country. In his book, he attempts to provide background information and to untangle misunderstandings concerning the country's problems.

How did the country slip into this state of permanent crisis? Engelhardt traces the path from the few golden years following independence in 1961 through the more than 20 years of dictatorship under Siad Barre to his overthrow in 1991 by rebel groups. This was followed by 13 years of civil war and chaos. Warlords fought each other for power, in the process destroying all state structures and any sense of security.

A profitable situation for some

Organized crime has flourished in the country. The smuggling of drugs, weapons, and people and (to the horror of Western industrialized nations) piracy have developed into the most important economic sectors in the semi-autonomous Puntland of north-eastern Somalia.

Ransom money seldom goes to the pirates themselves, but rather to their powerful backers. Clan leaders, politicians, Islamists, and other authorities pocket their share as well.

The presence of international navy vessels in the Gulf of Aden is not in itself sufficient to control the situation. This should come as no surprise, says Engelhardt. "Lasting peace at sea will only come about when Somalia finally enjoys peace, stability, and a degree of prosperity. Yet, no one wants to take any responsibility." A military operation on land could quickly and efficiently put an end to piracy, he says, however no Western army is willing to put their soldiers' lives at risk in ground warfare.

The rise of Al-Shabaab

In June 2006, new hands took hold of the levers of power. The Islamic Courts Union succeeded in driving the warlords out of Mogadishu. As a matter of fact, security and stability returned for a short time and the population breathed a sigh of relief. Contrary to European demands, the new rulers strictly rejected negotiations with the transitional government, which had been installed in 2004. The transitional government received support from neighbouring Ethiopia and the USA, who had raised the spectre of a "Talibanization" of Somalia.

Only a few months later, Ethiopian troops marched into Somalia and dislodged the Islamic Courts Union, a move that aroused international criticism. "The Islamists provided far greater security in Somalia than had existed for more than the previous decade. There were no indications that the Islamic Courts would have been politically dangerous," claims Ali Mazrui, an Islamic scholar quoted by Engelhardt.

Ethiopia's invasion, illegal according to international law, inevitably resulted in a radicalization of the Islamists and subsequently to an escalation of violence. Enjoying the support of various clans, the Islamist militias, in particular Al-Shabaab, stood opposed to Ethiopian and Somali soldiers, who had been joined by Ugandan troops from the 2007 AMISOM mission of the African Union.

The presence of foreign troops initially bolstered support among the population for the militant Islamists, who until late 2008 held control over almost all of the country. In May 2009, the battle for Mogadishu began. It would continue for the next two years, resulting in a massive number of civilian casualties and a steady stream of refugees.

Where aid workers require help

"There is probably nowhere else on earth that so urgently requires continuous assistance like Somalia," stresses Engelhardt. According to the UN, some four million Somalis are in need of assistance, and this figure does not include the over two million refugees in neighbouring countries. The population is not only at risk from the on-going civil war, but is also confronted with increasing droughts caused by climate change and resultant famines. We can still picture the images of the famine in 2011, in which 50,000 to 100,000 people died.

Humanitarian assistance in Somalia is, nevertheless, extremely dangerous. In addition to the danger posed by any unforeseeable escalation in violence, the kidnapping of foreign workers has become a lucrative business. The most problematic aspect of the situation is that aid in Somalia has a political dimension. "Whoever can provide food can quickly have the population on their side," claims Engelhardt. Aid workers should be neutral and offer help to all sides. "Whenever aid appears to be biased towards one group or another, then aid workers soon become the targets of the supposedly wronged party."

Most foreign aid workers coordinate their efforts from Nairobi and rely on the support of local Somali staff, who thereby find themselves in constant danger. Radical Islamists, in particular, often suspect them of being spies for the West and have them killed.

Has Somalia turned the corner?

In August 2011, the AMISOM troops received reinforcements and the militant Islamists finally left Mogadishu. By this point, the Islamists had long since lost any support they had enjoyed among Somalis as a result of their strict interpretation of the sharia and terrorization of the population. At the same time, Kenyan troops invaded the south of the country and the Ethiopian army was fighting in central Somalia.

By late September, Kismayo, the last bastion of Al-Shabaab, was taken. For the moment, the spectre of Islamism seemed to have been defeated. In August 2012, a new parliament was sworn in to replace the transitional government.

Has Somalia now turned the corner? Engelhardt's hopes lie with the Somalis themselves. "The Somali population has waited more than two decades for peace to return. They have persevered, but are now insisting on change. It will not be an easy path, but the everyday heroes are filled with courage and hope that the third decade after Barre's departure will be better than the previous two."

It is to these everyday heroes that Engelhardt has dedicated his book. He frequently permits them to express their views and presents their gripping and impressive personal stories. Although the large number of voices tends make things confusing, they nevertheless bestow an authenticity to the reports.

The West's short-term self-interest

Engelhardt's critical account of the actions of West on the Horn of Africa is particularly striking. He stresses the military and diplomatic mistakes of intermediaries, highlights irresponsible and incomprehensible interference, and provides convincing examples of how the West's short-term self-interest often took precedence over the interests of Somalis.

For instance, the US military engagement in the 1990s was more concerned with securing oil exploration agreements from the Barre era than in overthrowing the warlords.

Engelhardt has thus provided a well-based, detailed, and lively glimpse into the "failed state" of Somalia. In light of the fact that information on this region of the world is in short supply, this fascinating and equally horrifying portrait is undoubtedly of great merit.

Laura Overmeyer

© Qantara.de 2013

Translated from the German by John Bergeron

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de