Flashback from Beirut

When a chemical depot exploded in the Port of Beirut on 4 August 2020 and broad sections of the adjoining city district, together with the famous promenade, lay beneath ash and debris, the eyes of the world turned to Lebanon – once again because of a catastrophe. The accident killed 200 people and became a symbol for a broken country led into the abyss by sleepwalking politicians.

With constant conflict, corruption among political elites, an economic crisis and, to top it all off, the coronavirus pandemic, there had already been plenty of things troubling the people of Lebanon, and it seemed as if August 4 was the moment when the melting pot of problems finally boiled over.

It is generally crises and wars that cause Lebanon to feature sporadically in the European media. Yet most people seem oblivious to the fact that this nation, created in 1920 in the course of arbitrary, geopolitically motivated border demarcations by the British and the French, continues to be shaped by the upheaval that attended the period of its foundation.

And there is little talk these days of the 'Paris of the East' – for the longest time a veritable hub of art and culture – or indeed of Beirut being, as it remains, the literary capital of the Arab world. Arguably this has less to do with Lebanon, and far more with prevailing attitudes in European newsrooms.

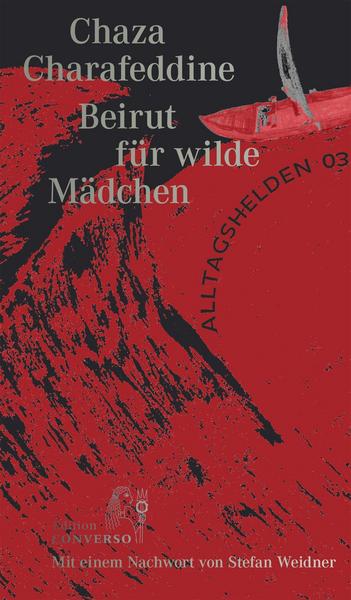

Where must we look, then, in order to find out what’s happening just beyond the ends of our upturned noses? The most obvious answer is: to literature. Chaza Charafeddine’s autobiographical novella Flashback was originally published in Beirut in 2012 by Dar Al Saqi. Now, translated into German by Gunther Orth and entitled Beirut für wilde Mädchen, it features several additional chapters and an enlightening afterword provided by Stefan Weidner.

The impact of world politics on a young life

Born and raised in Tyre in 1964, Charafeddine was forced to leave the seaside town as a child as the civil war, which began in the mid-70s, made life there too dangerous; she ultimately went to Switzerland and to Germany before returning to Lebanon many years later.

In the novella, the author and visual artist processes her childhood and youth, but also the time she spent abroad, in brief, episodic chapters. In laconic, clear language she unravels the story of what she experienced as a child, and what world history and power politics meant for a young person like her and her family.

Political earthquakes shape our existence, while penetrating deep into our private lives. One of the strengths of Charafeddine’s book is that it is not a work of non-fiction.

It would certainly have been possible for the central theme of Charafeddine’s own biography to be a biography of Lebanon since the 1960s. Instead, however, she has chosen a literary form which is neither novel nor memoir – neither fiction nor necessarily a chronicle.

She makes use of the basic framework of the Arab storytelling tradition, but frees it of all its baggage; she doesn’t embellish, largely dispensing with metaphors, pulling punches as unpredictably and casually as life itself. This creates an immediacy which makes it possible to experience the child’s perspective.

The little girl from a Muslim family, who attends a French school run by nuns, does, occasionally, recognise that there’s something unusual about her everyday life, but, for a time, she simply accepts it – much like the majority of children across the world.

One day – it is at the beginning of the civil war and she is eleven years old – a panicked hustle and bustle breaks out and her mother collects her and her sisters from school and there is commotion on the streets: she can’t make sense of the events. She is carried along and her world is turned on its head – as is the case again a few years later, as her parents increasingly turn to religion following the Islamic Revolution in Iran, which is of great significance to her Shia family:

"The gulf between us and our parents grew ever deeper, there were ever more things in which we became strangers to each other. They didn’t understand that we simply weren’t interested in practicing a faith, especially as we weren’t accustomed to it. And we didn’t understand why our parents wanted to force us into a world which, we could tell, we had no real connection to and which stood in contrast to everything we had known before."

Historical background for Western readers

In his afterword, Stefan Weidner provides a summary of the book’s historical background, and it is recommended that readers who are less familiar with the history of Lebanon read this before reading the book.

It is not political fractures and wars that finally lead Charafeddine to leave the country so much as her parents’ own motivation to do so: among the wealthier classes in Beirut, it’s normal to send your children to university in Europe – a decision which her father later regrets, as he has long since turned towards conservatism and away from the French influence that has shaped Lebanon for so long.

Charafeddine explains how strange some elements of the Swiss and German ways of life are, only to come to the conclusion, after years away, that the Lebanese are strange too, in their own way. She turns the discussion of cultural differences on its head, holding a mirror up to her audience as much as herself: “It’s very confusing, actually. But not just for a non-Lebanese person, it’s just as confusing for us too.”

Beirut für wilde Mädchen is Chaza Charafeddine’s first published piece of prose (following other published pieces in anthologies and magazines) and it is a highly successful one. She succeeds in interweaving art, autobiography, history and stories, falling back on traditions of storytelling, and building on them by finding her voice and lending her experiences a universality of their own.

© Qantara.de 2021

Translated from the German by Ayca Turkoglu