When minorities become pawns in a power game

The stronger the competing Islamist terrorist militias of IS and the Nusra Front become, and the more brutal Syria's civil war gets, the easier it is for the Syrian regime to portray itself as the sole force capable of protecting the country's civilians. Despite the fact that the soldiers and mercenaries commanded by Bashar al-Assad are responsible for the vast majority of the hundreds of thousands of deaths in Syria, many in the West stubbornly stick to the view that the dictator remains the lesser evil. After all, they claim, he protects Syria's minorities.

It is therefore interesting to consider the different ways in which the West and the Assad regime view the matter of minority protection. The essential concern of the West is based on its conviction that a genocide against Christians and Ismailis must be prevented and takes account of the fact that an entire society could rip itself apart if minorities are persecuted.

Assad, by contrast, treats the issue of minorities in a pragmatic manner. It is within his power to protect minorities – or not – as he sees fit. The essential needs – in the truest sense of the word – of those requiring protection are of no concern to him. His one and only interest is in holding on to power.

Assad and the Yazidis and Ismailis

In August 2014, the world's eyes were opened by news of the siege of Sinjar by IS and its persecution of the Yazidis. At the same time, the Syrian regime massively decreased its presence in the region surrounding Salamiyah, an area that IS openly threatened to attack and that is regarded as the unofficial capital of the Ismaili minority in Syria.

The anxious inhabitants of Salamiyah observed the withdrawal of troops and heavy artillery. The regime left just enough fighters and weapons in the city so as not to create the impression that it was abandoning it. For the most part, those who remained were militias loyal to the regime who have a reputation of being the first to flee when the going gets tough. The residents of the city felt anything but protected.

A member of the high Ismaili council promptly requested a meeting with President Assad and pleaded for reinforcements – without success. According to Maher Esber, an activist from Salamiyah, "the answer was: 'We tried to mobilise 24,000 men from Salamiyah to join the Syrian Army, but they refused. Let them protect the city.'"

The IS militia draws closer

It is difficult to ascertain the extent to which the Syrian regime actually withdrew troops from Salamiyah. Whatever the answer, there can be no doubt that IS is drawing closer. In March, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported that 70 soldiers loyal to the regime were killed at checkpoints near Salamiyah.

The regime, which usually remains silent about its losses, also cited this figure. A particularly fierce attack on a neighbouring village occurred in late March this year. The fighters appeared in the early morning hours on motorcycles and killed more than 30 villagers, including women and children.

Mohammad A., an activist from Salamiyah who does not wish to reveal his full name out of concerns for his safety, told us in an informal discussion that "soldiers from the 47th brigade and the National Defence Forces" had abandoned the village shortly after the attack began, apparently in a bid to call in reinforcements. But when other residents telephoned Mansuriya, a military base seven kilometres away, no reinforcements came. Instead, the area was indiscriminately bombed, resulting in many civilian deaths. This account was substantiated by a number of other activists from Salamiyah via social media.

Despite these dramatic incidents and although IS has left no doubt about its intention to advance towards this region west of Hama, the regime has done nothing in the intervening period to increase its presence here. Instead, it has relegated its authority to militias under the umbrella of the National Defence Forces – irregular fighters that have been relabelled as a quasi-state organisation. Most of these men have received little or no military training; they have a reputation for plundering and terrorising their fellow citizens.

Gaping omissions in media reports

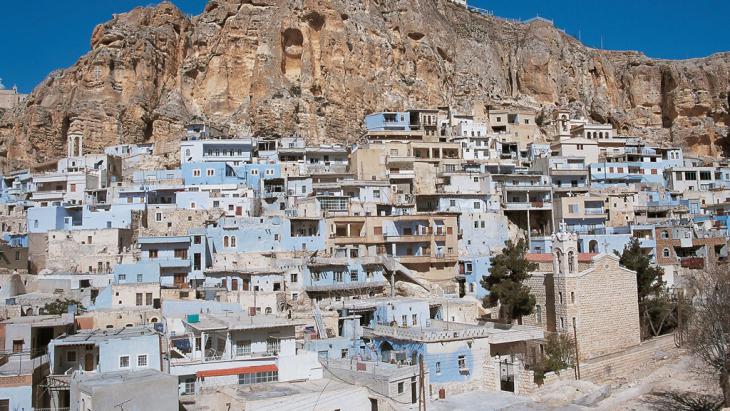

There is a long tradition in Syria of dealing with minorities in a manipulative manner. In 2012, when rebel attacks on the monasteries and churches of the renowned Christian city of Maalula made the headlines, a crucial point was left out of most reports, namely that the regime had no military forces stationed around the city to protect it against raids by Islamist rebels. Instead, they were intentionally positioned between the churches, thereby exposing these sites to attack. At the time, the Lebanese-based journalist Ana Maria Luca published an excellently researched article exposing the political misuse of the Christian community in Syria.

The Ismailis are, after the Christians, probably the best-known Syrian minority. This is largely attributable to the community's prominent spiritual leader, the Aga Khan, and the development network associated with his name. In keeping with its cynical machinations, the Assad regime regards his international fame as an asset. In order to be appreciated in its role as protector, the regime regularly reminds minorities of the dangers they face in their vulnerable position. This is one means of keeping them from revolting against the authorities.

A desperate dictator is capable of anything, and the actions of Bashar al-Assad leave no doubt as to the truth of this dictum. Minorities in Syria are increasingly aware of how much they have become pawns in the power game being played by the regime, which is now only capable of controlling just a few regions of the country. And all the while, the West plays along.

Haid N. Haid and Bente Scheller

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by John Bergeron