Iran’s doctored schoolbooks and the disappearing girls

"To whom do I give my little heart?" is the title of a poem by the modern Iranian poet Nader Ebrahimi. It is also to be found in a school Farsi textbook for 12 and 13-year-olds. Ebrahimi is famed beyond the borders of Iran and has won several international prizes, including the UNESCO prize for education in 1970. One sentence of his poem has been changed in the new schoolbooks. The original is: "My heart I give to the fighters who have driven the enemy from our house". But schoolchildren now read: "My heart I give to him who has fought for Islam."

The wife of the poet (who died in 2008), the teacher and translator Farzaneh Mansouri, alerted the public to this tampering a few days ago.

She said that she had complained to the ministry of education about the falsification of Ebrahimi’s work. The sentence was to be corrected, she added, or she would be going to court over it. So far, Ebrahimi’s poems and books have survived the critical eye of the ministry’s control committee, and are on the list of works permitted to be taught in schools. This means they have to accord with the image of Iran’s religious society set out by its leaders.

#فرزانه_منصوری همسر #نادر_ابراهیمی درخصوص تغییریکی ازداستانهای نادر ابراهیمی درکتاب هفتم دبستان، گفت:این داستان ازکتاب «قلب کوچکم را به چه کسی بدهم» انتخاب شده است.من اعتراض خودم را اعلام کردم؛ اما جوابی نگرفتم واگرمسئولان دست به اصلاح اتفاق رخ داده نزنند، اقامه دعوی خواهم کرد. pic.twitter.com/2xRUejmXdU

— خبرگزاری هرانا (@hra_news) November 7, 2020

A losing battle

"Ever since the religious revolutionaries took power in 1979, they’ve been attempting systematic brainwashing in schools and universities, to implant their ideology in the heads of the next generation," explained science journalist Erfan Kasraie in interview. Kasraie lives in exile in Germany, and has done a lot of work on the content of school textbooks and reference books in Iran.

"These texts have been manipulated to fit the government’s ideology for more than 40 years now, and it hasn’t worked. It’s astonishing how unreligious young people in Iran have become. You don’t see anything comparable in other Islamic countries. And for that reason, there is a new idea for the Islamification of schoolbooks almost every year."

There is a long list of notable writers and intellectuals whose works have been removed from schoolbooks, to make space for new stories about martyrdom and the heroes of the Islamic Republic.

Two years ago, a poem by Mehdi Achawan Sales, one of the pioneers of Persian-language free verse, was replaced in a final-year Farsi book by a poem about a volunteer Iranian fighter beheaded in Syria by IS.

A poem about a hero of the Islamic Republic is more important than literary works for young Iranians, the education ministry argued in 2018, pointing out that the change was made in line with the national curriculum.

More and more adaptations

That curriculum was issued by the Iranian cultural authority, the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution, in 2012. It was the fourth in the past forty years. It stipulates that the contents of schoolbooks should be adapted once again to the value system of the Islamic Republic of Iran. How exactly this should be done is not explained. Instead, there are fresh surprises almost every year.

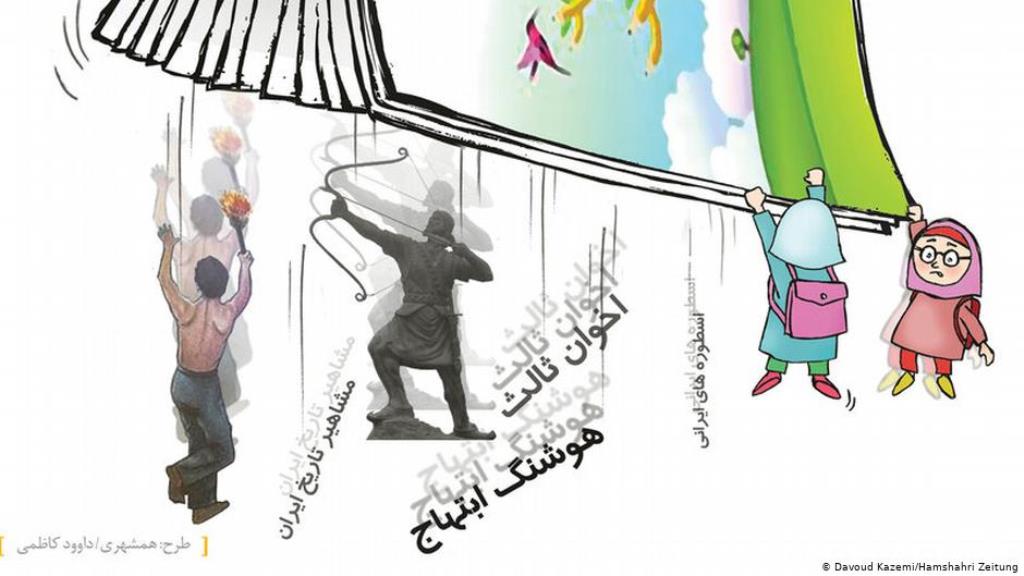

Sometimes poems vanish from Farsi books; sometimes Persian kings and kingdoms disappear from history books. At the start of the current school year, it was the two girls on the cover of the maths book for nine-year-olds. Now three boys sit alone under a tree of numbers and mathematical symbols. The removal of the girls caused a storm of outrage, especially on social media.

"These schoolbooks are used to establish the values of the political system in Iranian society. In this system, girls are systematically neglected," said Roshi Rouzbehani. The author and illustrator of the book "50 Inspiring Iranian Women" grew up in Iran and experienced the Islamic Republic’s school system first-hand.

"In this system, the ideal woman looks after the house and the children. Her most important role is as a good wife and mother. But we know that, despite all the obstacles placed in our path, we are much more than that." In her book, published in London, Rouzbehani profiles Iranian women who are inspirational in the eyes of many Iranians despite – or perhaps because of – the fact that they don’t fit into the Islamic Republic’s value system.

One of them is the mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, who in 2014 became the first woman to be awarded the Fields Medal, a kind of Nobel Prize for maths. Mirzakhani, who was born in Iran in 1977, taught at Stanford University in the USA from 2000 onwards. She died of breast cancer in 2017. Many Iranian parents are now sticking a picture of Mirzakhani – without a headscarf – to the cover of the altered maths book and posting photos of it on social media.

Following a wave of criticism, the schools minister Mohsen Hajhi-Mirsaji was forced to make an apology. He described the removal of the girls from the book cover as a "tasteless act". Hajhi Mirsaji has announced that this will be corrected next year. Whether the original version of Ebrahimi’s poem will appear in the Farsi book then as well remains to be seen.

© Deutsche Welle 2020

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin