Stranger than fiction

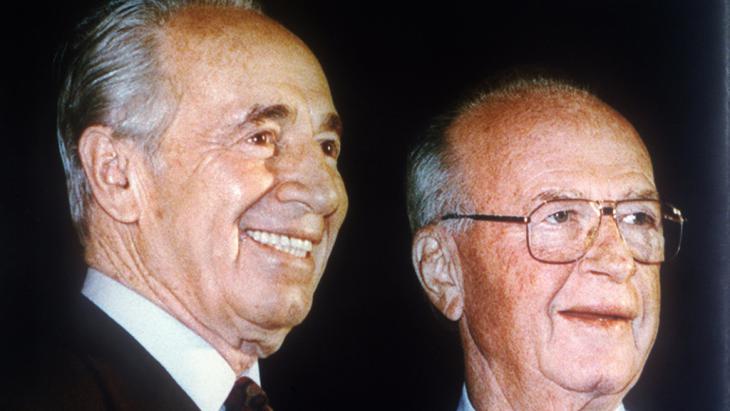

He fought "tirelessly" for "peace". He was "a man of reconciliation", an "exceptional politician". He embodied "the grace of Zionism". Governments and media are in agreement: in Shimon Peres, we have lost a "great statesman".

A quick reality check leads to the suspicion: something's not quite right here. The situation of the state of Israel cannot be described with the word "peace" – neither regarding its relationship with its neighbours, nor within its own borders. There is nothing "gracious" about the metre-high concrete wall aimed at separating Israelis from the Palestinians, the cyclical outbreaks of violence and the arsenal of nuclear weapons, not to mention the aggression of the public and private political discourse. Shimon Peres was involved in all this, in some cases playing a decisive role.

There are essentially two responses to explain the latent discrepancy between the solemn tone of the obits and reality. Firstly: perhaps the statesman Shimon Peres wasn't quite so "great". In any case he must have been much too weak and small to realise his "visions for peace". Secondly: perhaps the image of the Prince of Peace is a flimsy ideal, one that only offers a highly inadequate description of the political figure of Shimon Peres. Perhaps "reconciliation" with the neighbours was not the determinant motive of his actions at all. One must seek out the truth in a combination of both answers.

Peres had it easy in the winter of 1995/96. On 4 November 1995, a national-religious fanatic assassinated serving Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin at a peace rally in Tel Aviv. Peres, who had also been taking part in the memorable demonstration in support of the "Oslo Accord", was shunted up from the post of foreign minister to the helm of government.

There was every indication that he would win the impending elections and be confirmed in office. He was carried on a wave of sympathy at home and all over the world. Many Israelis were shocked at the hatred that had led to the murder of Rabin. Peres could have reined in those fanatics agitating against the peace accord with the Palestinians, clipping the political wings of their spokesmen Ariel Sharon and Benjamin Netanyahu.

A grave political error

But Peres eschewed confronting his domestic political opponents head on. In the midst of the election campaign, he instead launched the dreadful military operation in Lebanon with the preposterously poetic name "Grapes of Wrath". Intended to weaken the Tehran-sponsored Shia Hezbollah militia, this did not happen. Instead, in one single bombardment, Israeli artillery killed more than 100 people who had sought refuge in a UN building in the southern Lebanese village of Qana.

With the campaign, Shimon Peres wanted to demonstrate his strong man credentials, national security his top priority. The result: Peres was beaten in the general election on 29 May 1996 and Netanyahu became prime minister. This defeat at the polls was one of the gravest political errors of modern times. This failure is the decisive moment in Peres' political biography.

The "peace process" lay in ruins. Peres was defeated by those who had preached hatred and paved the way for the murder of his party colleague. Before the assassination, Sharon and Netanyahu had appeared at nationalist meetings during which an image of Rabin in a SS uniform was displayed.

The tragic reverberations from the six months between 4 November 1995 and 29 May 1996 can still be felt to this day. Israel will perhaps never again recover from the consequences. Peres himself was able to live with it very well. In 2001, he joined the government as foreign minister and junior partner in the grand coalition led by the ultra-nationalist Prime Minister – Ariel Sharon.

The wheeler-dealer

Wheeling and dealing with political opponents was a constant theme of Peres' career. Even back in the 1980s, he entered a coalition with the Likud leader at the time Yitzhak Shamir, serving for two years as Prime Minister. As part of a "rotation" agreement within a grand coalition and when the head of government was murdered: this is how Peres came to be at the helm of government twice for a limited period of time. He consistently lost parliamentary elections.

He also failed in his first attempt to get elected to the post of president. It was only when the incumbent Moshe Katsav, who had beaten Peres in the poll, was convicted of the rape of a number of female office staff, that Peres eventually managed to claim the highest – but purely representative – public office in 2007, at the advanced age of 84.

Under his leadership, the social-democratic Labour Party experienced an unparalleled decline. It fell from the status of a mainstream government party to that of a splinter group. The fate of Israeli social democracy appears to anticipate that of European countries: party supporters have turned to the xenophobes, 15 years before in France, "Parti Socialiste" voters switched their support en masse to the Front National and in Germany, many SPD voters transferred their allegiances to the AfD. In economic matters, Peres was of the neoliberal persuasion. He never paid any particular attention to improving social equilibrium. The Jerusalem professor of history Zeev Sternhell accused Peres of wrecking the once proud Israeli Labour Party.

The eternal loser

Although Peres was the eternal loser in domestic policy wranglings, he held out longer than anyone within the Israeli political establishment – 70 years, to be precise. He owed his rise to the fact that as a young man, he became a confidante of state founder David Ben Gurion. Peres, who never served as a soldier himself, showed in the early days a talent for the procurement of weapons, either through acquisitions abroad, or through the creation of the nation's own arms manufacturers. As a young secretary of state in the defence ministry, he played a central role in the 1950s in arming Israel with a nuclear arsenal. Peres built up the decisive contacts with France, a country that supplied the key components of nuclear technology.

So, just a few years after the Shoah, Peres laid the foundation stone for the long-term military superiority of Israel over its neighbours. This was initially undoubtedly a great achievement, in view of the threat from Arab nationalism that had become considerable in the course of the 1947/48 Arab-Israeli War. Whether this supremacy, as Peres liked to maintain later, represented an important precondition for peace with the neighbours, must be contested in view of how things then panned out.

After four wars in the Middle East and the outbreak of the Palestinian intifada in the late 1980s, Peres wanted a peace settlement with the most immediate Arab neighbours. There are no doubts over that. The treaty with Jordan and the agreement with the Palestinians, which initially conceded them a certain degree of autonomy in parts of the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, are the result of this intention.

The "New Middle East"

But his catchphrase "New Middle East" (ha-mizrakh ha-tikhon he-khadash) concealed a quite specific idea of what this peace should look like. Palestine, Jordan, Syria and at least most of Lebanon should make an effort to get along with Israel. Economically, Israel should profit from this peace community in the same way as Germany from the EU.

But even more important however were the strategic considerations. The "moderate Sunni majority population" living in the direct neighbouring states should form a security buffer. This was because the political establishment in Israel had made a new main enemy: the (Shia) Islamic Republic of Iran. Peres' "vision" of the New Middle East was wholly geared towards excluding Iran from any regional peace arrangement. This line was closely coordinated with the US.

Peres and other Israeli leaders repeatedly sold the idea that it was necessary of "extending the hand of reconciliation to Arafat", by warning against the "threat posed by the Shia ayatollahs". The focus should be on the latter. That Iran was "just a few months away from completing the atom bomb" (which would cancel out Israeli military superiority), was a mantra regularly trotted out by Shimon Peres from the 1990s. In these circumstances it was not surprising that Iran and the Palestinian Islamists of Hamas found common cause and even overcame confessional barriers in the process.

Risking political isolation

The Israeli contemporary historian Khagai Ram disclosed this association in a striking manner. With the nuclear deal of July 2015, US President Obama, the other members of the UN Security Council and Germany positioned themselves clearly against the logic of Shimon Peres, which dictated that Iran must be excluded from any Middle East peace order. This could undoubtedly result in the danger of political isolation for Israel.

In their obituaries, the eulogists admiringly contrast the "greatness" of the "last of the founding generation of the state of Israel" with the mediocrity of the younger political class. The reason for this could be that western politicians and media elites like to see themselves reflected in the Nobel Prize laureate from Tel Aviv, who was himself so European in character. The role Peres himself played in the decline of Israeli political culture over the past two decades is graciously overlooked.

Fortunately, when he was a young boy Shimon Peres was able to emigrate from Wishneva in eastern Poland with his family in 1934. This way, he evaded being murdered by the Germans. May he rest in peace after an eventful 93-year life. The world must hope that this will also apply to an early achievement of his political career: the nuclear weapons stored beneath the Negev desert. The world must hope that it must not ever remember Shimon Peres due to a nuclear conflagration somewhere in the Middle East.

Stefan Buchen

© Qantara.de 2016

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

Stefan Buchen works as a television journalist for the ARD magazine Panorama. From 1993 to 1996, he studied Arabic language and literature at the University of Tel Aviv. He worked as a journalist in Israel from 1996 to 1999. He speaks fluent Arabic, Hebrew and Farsi.