The Ongoing Battle for the Female Body

On 20 December 2012, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution aimed at ending the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM). Two days later, the national referendum in Egypt voted in a new constitution. What do the resolution and constitution bode for both the body politic and female bodies in Egypt?

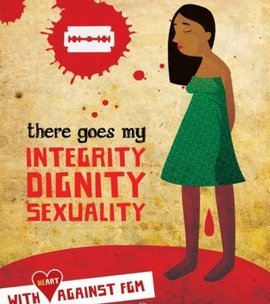

UN women called the resolution a "significant milestone" in the global drive to end FGM, which has been perniciously imposed on young girls as a local custom and religious prescription. The result of sustained international effort with key input from Egypt, the resolution provides another tool for national governments with the political will to eradicate FGM and its assault on the right of women to bodily health and personal integrity.

Borrowing from and extending the 1971 constitution provisions, the new Egyptian constitution stipulates that laws must be grounded in the Shariah, allocating power to the state and its various branches to determine what this means. With tafsir (interpretation of the Koran) in the hands of the government, hermeneutics becomes politics.

The Islamist pro-FGM campaign

With Islamists now holding major political power, how will women fare? In the National Assembly, which has since been dissolved, Islamists called for the re-institution of FGM, which is currently criminalised, along with the elimination of a minimum marriage age, the extension of men's custody over children, and the limiting of women's abilities to enact divorce. Such a 'package' speaks to the strengthening of men's power and control over women and children with religion invoked to achieve this end.

Going back millennia in Egypt and other Nilotic lands, FGM is a cultural practice that entails cutting the genitalia of young girls in order to mute or extinguish female sexual desire. It is done to preserve the sexual purity of females, which is tied to the honour of men and the family (men's own behaviour is incidentally exempt from such ties to honour). While not called for by any religion, people have used religion to buttress the perpetuation of FGM imposed on Muslim and Christian girls alike.

FGM is not an Islamic prescription; it is not mentioned in the Koran or in fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence). Yet Islam has been wantonly used to sustain FGM's gruesome assault on girls' bodily integrity and well-being. This is mind-boggling for those who see Islam as a religion that affirms the moral and bodily integrity of all human beings and not one that endorses the infliction of corporeal mutilation and suffering.

Brief history of opposition to FGM

Serious efforts to stop FGM go back to the middle of the twentieth century when it was prohibited by the Nasser government in 1959. At the time of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo in 1994, national and international energies converged to intensify the FGM eradication campaign.

In the run-up to the conference, veteran social reformers Aziza Hussain and Marie Assad established a task force, which served as a vocal point for groups working in various professional and associational contexts. The highly networked task force supported activists reaching out to rural areas, co-ordinating with local efforts to eliminate FGM.

Intense public exposure elicited contradictory responses from Islamic religious scholars on FGM. The Sheikh of al-Azhar at the time, Gad al-Haq, declared that female circumcision (as he and other religious scholars called FGM) was a religious requirement.

The Grand Mufti, Muhammad al-Tantawi, issued a fatwa stating that female circumcision was not Islamic. Islamist lawyer Salim Al-'Awwa wrote in Al-Sha'b that female circumcision was neither required nor praiseworthy. Shaikh Farid al-Wasil (who became Grand Mufti in 1996) wrote in al-Akhbar: "There is no retreat from the previous fatwas on female circumcision issued by Dar al-Fatah which confirmed there are no religious texts within the domain of Islamic Shariah which command or prevent female circumcision."

The fight to legalise FGM

In the tumultuous political context following the ICPD, the ban on performing FGM in hospitals was lifted. When the ban was re-instated in 1996, Shaikh Yusif al-Badri, a member of the Higher Council for Islamic Affairs, and gynaecologist Munir Fawzi, filed suits against the new ban. They claimed the ban violated the 1971 constitution, declaring the Shariah to be the source of all law in Egypt. They cited the authority of the former Shaikh al-Azhar Gad al-Haq and backed it up with al-Badri's readings of Islamic jurisprudence.

Reviewing the case, the State Council declared in 1997 that the ban did not violate the constitution. Keeping up the pro-FGM offensive, Dr. Abu 'Umaiyra, a former dean of the College of Usul al-Fiqh at al-Azhar, published an article in 1998 defiantly entitled: "Female circumcision is Legislated by God despite its Prohibition by the Courts."

The ongoing efforts of civil society led by NGOs working at national and local level were re-enforced by the support of the National Council of Childhood and Motherhood (NCCM, est. 1989) which was stepped up around 2001 after Moushira Khattab became secretary-general.

At local level, when people grasped more fully the grave health risks associated with the practice and understood that neither Islam nor Christianity condoned FGM, which is a harsh social practice, they began to stop it and enthusiastically joined the campaign against it. They turned FGM, which had been seen as a badge of honour, into an act of disgrace. Uprooting a deep-seated habit requires continual vigilance and encouragement.

Quo Vadis, Egypt?

With the ascendancy of the Islamists, FGM is now finding renewed support. Last year, people heard Islamist parliamentarians calling for the return of FGM from the floor of the National Assembly. In the run-up to the final round of the presidential elections last spring, some members of the Muslim Brotherhoods' Freedom and Justice Party went around villages offering reduced-rate FGM operations. They were spotted, for example, in Minya Province in the village of Abu Aziz. When their FGM services attracted public attention, they abruptly vanished, fully aware that that performing FGM was a criminal act; they denied any involvement in peddling the practice.

So what is the situation regarding FGM at the moment? The global jubilation attending the resolution was tempered locally by the voting in of the new constitution and the political context in which it was drafted and approved. With the new UN declaration, will there be another round of discrediting international instruments as "anti-Islam"? Will articles of the constitution be mobilised in an effort to enable the practice of FGM, which respected religious figures have declared beyond the bounds of Islam?

What exactly are the procedures and mechanisms for determining if an act – for example the outlawing of FGM – is in accordance with the Shariah? According to article 4 of the constitution, al-Azhar must be consulted about compliance with Shariah (although the scholar experts may differ producing another problem).

If religious scholars uphold the previous pronouncement that FGM is not Islamic and a parliament dominated by Islamists votes in favour of allowing FGM, what then? Is the Shariah, which is open to various readings, to be a freely sought moral guide and inspiration or merely reduced to a political imposition?

Margot Badran

Editor's note: since this article was written, Egypt's Higher Constitutional Court has affirmed the legality of the ban on FGM in Egypt.

Margot Badran is a historian and senior fellow at the Alwaleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding, Georgetown University and a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center of Scholars.

© Qantara.de 2013

This article was previously published by Ahram Online.

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de