Looking for a Third Way

Tunisia and Egypt are squaring up to huge economic challenges. According to initial projections from the Tunisian central bank and the Egyptian economics ministry, both countries will require between 20 and 30 billion US dollars over the next five years if they want to raise general living standards and tap into underdeveloped regions.

The US and the EU have already made it quite plain that their coffers are empty, and that in view of the debt crisis, they are not about to allow themselves any extravagances. In May of this year, at the G8 summit in Deauville, the world's richest nations pledged 20 billion to Tunisia and Egypt over a two-year period, consisting of loans scheduled before the revolutions.

Arab nations will also be in no hurry to help their neighbours with their democratisation processes. And EU plans to set up a Mediterranean Bank – in discussion since 1995 – were finally shelved in May. Unlike Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Mediterranean countries will not have their own bank for reconstruction and development.

Instead, together with the IMF and the World Bank, the main lenders will be the European Investment Bank (EIB) – which is offering loans to the tune of six billion US dollars until 2013 – and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

Hopes of foreign aid dashed

In Tunis and Cairo, there had been intermittent hopes for something akin to the US Marshall Plan for rebuilding Europe after World War Two. Economists estimate that such a programme would cost the equivalent of funding the Iraq war for a two-month period, or three percent of the cost of German reunification in 1991. Today, no one is banking on outside help.

Accordingly, the IMF and the World Bank are encouraging Tunisia and Egypt to continue liberalising their markets and seeking loans from multinationals. International creditors and western conglomerates have long had their foot in the door, but want greater freedom of movement. In their view, public-private partnerships (PPPs) now represent the requisite silver bullet.

PPP means that for a fixed period of time and instead of the state, private companies provide and operate for profit a public service such as water, health, or similar. Even though such arrangements are only temporary, they do amount to a privatisation of the public sector.

For the business world and international institutions, PPPs are a natural instrument to finance infrastructural measures in Mediterranean countries. But it must be stressed that this financing model can only function under particular conditions. Firstly, PPPs require low interest rates and healthy banks – conditions not currently in place in either Tunisia or Egypt. Many banks have dubious debts and all in all, there is a lack of expertise necessary for complex financial operations.

Secondly, the public operator must be in a position to ensure that its own interests and those of the taxpayer are being served, and that private-sector partners can effectively fulfil their obligations. Or in other words, the state and its local institutions must have the necessary expertise required to evaluate and realise the relevant PPPs. PPPs don't necessarily require a strong state, but a competent one capable of negotiating a solid operative framework. Will future administrations in Egypt and Tunisia be up to this task?

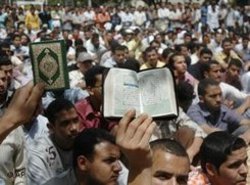

The social attitude of political Islamism

If there is a middle way, an approach that is some way between over-hasty liberalisation and a return to a planned economy, it will certainly not be discovered by the religious political parties. The Egyptian economist Samir Amin cites the example of the Muslim Brothers to illustrate this point, saying that Islamism is happy to align itself with liberal, mercantilist theories and – contrary to popular belief – pays only passing attention to social issues: "The Muslim Brothers are in favour of a market-based economic system which is totally externally dependent," he says.

"In the past decade in particular, they have opposed big strikes by the working classes and the peasants' struggles to retain ownership of their land," he goes on to say. "So the Muslim Brothers aren't moderates except in the sense in which they have always refused to formulate any economic or social programme. In addition, they accept the US hegemony in the region, and that makes them useful allies for Washington."

There is much talk about the charity work of Islamist organisations. This tends to overlook the fact that they are defending a fixed order and refuse to contemplate or develop policies that will actually reduce poverty and inequality. Instead, political Islamism favours neo-liberal policies and oppose any redistributive policy that uses taxes. The latter is considered impious, with the exception of the zakat, the compulsory donation of a portion of income to charity, which is one of the five pillars of Islam.

This explains why Islamists have never tried to reach an understanding with the global justice movement, which they quite simply view as a new manifestation of communism. It is reasonable to suppose that strong Islamist parties will not bring about any major economic revolutions.

So Tunisia and Egypt are now tasked with finding a "third way" – something that most nations of the former eastern bloc have not managed to do. Popular revolutions must not become the foundation for an all-powerful capitalism that undermines the social transformation of Egyptian and Tunisian society. Ensuring that this is allowed to take its course will depend on the establishment of a new economic order primarily focused on reducing social inequalities.

© Die Tageszeitung/Qantara.de 2011

Akram Belkaïd is a freelance journalist and essayist, he recently published the book "Être arabe aujourd'hui" (Being Arab Today)

Translation: Nina Coon

Qantara.de editor: Lewis Gropp