On the rocky road to democracy

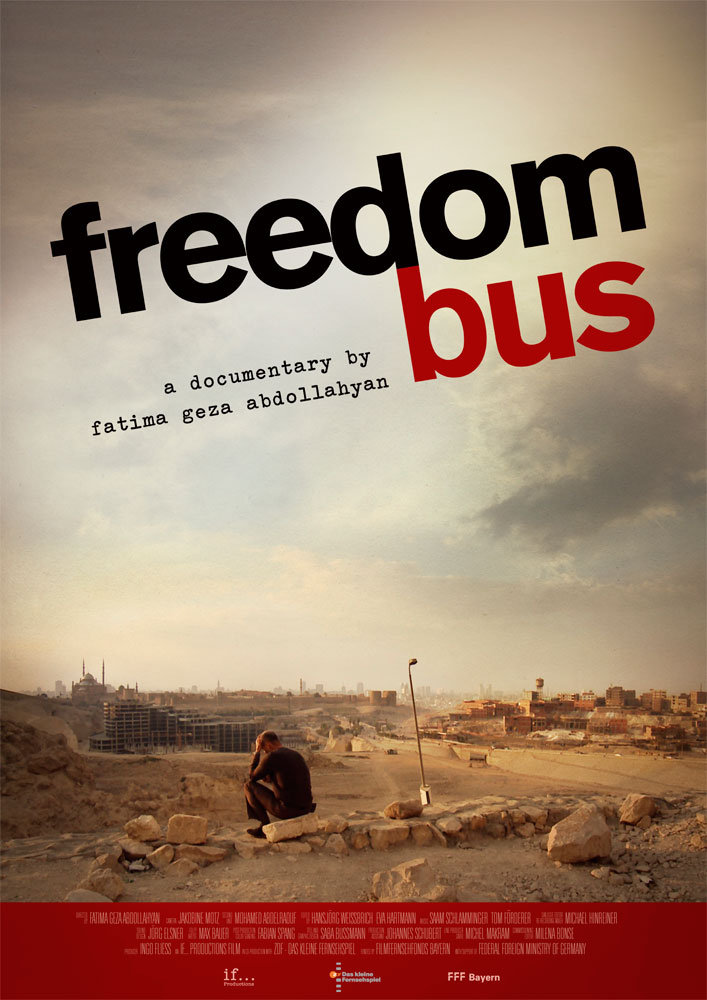

Like her debut film in 2010, "Kick in Iran", Fatima Geza Abdollahyan's second documentary is devoted to a politically charged topic. The 90-minute documentary "Freedom Bus" takes the viewer on a journey through Egypt, a country making slow progress on the road to the unknown territory of democracy.

"Freedom Bus" tells the story of 39-year-old Ashraf Sharkawy, who abandons his comfortable life as a successful manager in Germany to launch a democratisation campaign in Egypt – by the people and for the people – shortly after the overthrow of Mubarak.

Sharkawy, who was born into an Egyptian family in Germany and grew up there, developed the Freedom Bus campaign with the help of a few volunteers. The aim was to raise awareness of the basic ideas and concepts behind democracy in order to encourage and enable Egyptians to take their future into their own hands.

From March to December 2011, Abdollahyan accompanied Sharkawy and his Freedom Bus on every kilometre of the journey through the provinces and witnessed the many failed attempts and obstacles that plagued this non-partisan democracy campaign in Egypt. Her film focuses mainly on the implementation of the project from an organisational standpoint, while also helping viewers to understand the emotional conflicts Sharkawy faced.

The film also highlights the often polarised views of democracy held by the Egyptian people. As they travel from city to city, Sharkawy and his team are continually bombarded with questions about their party affiliation and sponsors and are asked to respond to the ongoing debate about the possibility of a liberal form of Islam in Egypt.

Alienated from one's own culture

With a bachelor's degree in political science, a master's in international relations and an additional degree as a documentary filmmaker, Fatima Geza Abdollahyan certainly has an interesting background. The German-Iranian director gets her inspiration from Middle Eastern legends in particular.

Asked where she got the idea for "Freedom Bus", she replies, "Ashraf and I are old friends. We have much in common, since we were both born in Germany, come from middle-class families and have enjoyed an excellent education, as well as all the privileges that come from growing up in Germany."

In recent years, she and Ashraf often discussed what they owe their parents and their native countries for all they have done for them. She notes however that "at the same time, we often felt alienated from our cultures and sought ways to get back to our roots."

According to the director, Sharkawy had the idea for the Freedom Bus shortly before Mubarak's resignation. In March 2013, he decided to drop everything and return to Egypt to put his idea into action. He wanted Abdollahyan to join him on his journey with the Freedom Bus and to document the project from start to finish.

Although Abdollahyan considers the Freedom Bus film project to have been an overall success, the struggle to educate people about democracy in Egypt was a bumpy ride. This is illustrated by a scene showing a heated dispute between two men about whether there could ever be such a thing as a liberal form of Islam. Conflicts arose again and again when visitors to the bus called into question the organisers' agenda and intentions – a sign of growing xenophobia in post-revolutionary Egypt.

Rocky road to democracy

"It was difficult for us as a film team to document the work of the Freedom Bus," says Abdollahyan. "At some point we had to stop shooting on location and send our camerawomen back. We then had to work with an Egyptian cameraman in order to overcome some difficulties. Sometimes visitors to the bus did not let us film, calling us 'Americans' and wondering what the film had to do with the actual Freedom Bus campaign."

"Some of their reactions make sense though," adds Abdollahyan. "After the revolution, the country was like an open wound – people didn't know who to trust and who to believe. So I understood their mistrust."

Despite many positive experiences during the Freedom Bus campaign and the fact that the film project was very successful, not enough information about the goals of the campaign was communicated either through the Egyptian news media or by the film itself. Although prominent politicians, such as Pakinam Sharkawy, Mohamed Morsi's assistant during his one-year term in office, or the liberal industrialist Ziad Ali, do make appearances in Abdollahyan's documentary, these cameos go without comment, raising questions as to the film's orientation and intentions.

Not an expanded form of journalism

Furthermore, the documentary offers little relevant background information on important political events that coincided with filming, such as the brutal clashes on Mohamed Mahmoud Street and the Maspero massacre in Cairo in the autumn of 2011.

Abdollahyan is known for her minimalist style. She deliberately avoids using background music and narrative in her films and lets only a few figures speak on film.

"I believe that documentaries can only arouse sympathy; they are not an extended form of journalism. After all, journalism deals only with facts. So if I manage to open up a space where I can have my own personal experience, and if I manage to move the viewer emotionally, then they will want to seek out the facts for themselves," she says.

"I would never make a film and claim that I'm an expert on that topic – my expertise lies in the point of view of my protagonists," she adds.

Sharkawy is still living in Egypt and trying to get a permit to go on a second tour with the Freedom Bus. That would be an excellent opportunity for Abdollahyan and Sharkawy to join forces again and to document possible changes that have taken place in Egyptian society since the beginning of the 2011 campaign.

Maha El Nabawi

© Goethe Institute Cairo 2013

Translated from the German by Jennifer Taylor

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.dev