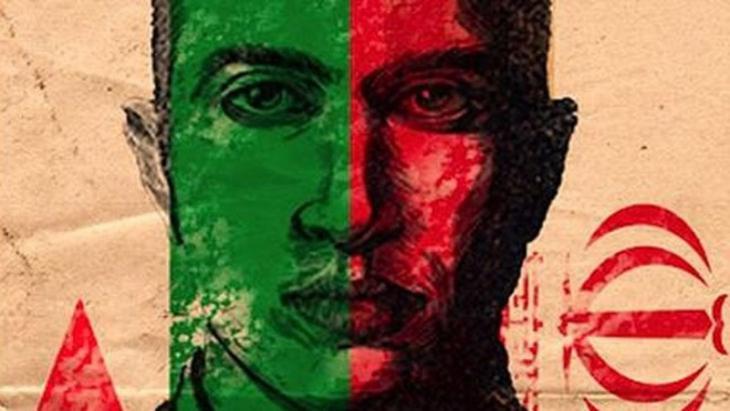

A friendship that inspires hope

Some stories sound too impossible to be true, for example that of Mosab Hassan Yousef. The son of one of the founding members of the radical Islamist Hamas movement, whose declared objective is to eliminate Israel, Yousef became an informant for the Israeli domestic secret service. For ten years, he foiled planned terrorist attacks that targeted Israelis. Soon after his contact on the Israeli side, Gonen Ben Itzhak, was dismissed from service, Yousef ended his co-operation with Israel. He converted to Christianity and settled in the USA. The new documentary "The Green Prince" by filmmaker Nadav Schirman, an Israeli who lives in Germany, turns this story into an enthralling detective story about terror and violence, but also about trust and friendship.

***

This is your third film about espionage and terror. What is it about these subjects that fascinates you so much?

Nadav Schirman: For me, the three films are about a relationship under enormous pressure rather than about spying or terrorism. This insight into this secret world makes this moving human drama only more interesting. Those who know me would say that these films are really about me. As someone who grew up in many countries, I deal with questions of identity in all three films.

My first film, "The Champagne Spy", is about a father-and-son relationship. The father is a Mossad agent and the film shows the emotional price he pays for being a spy. My second film, "In the Dark Room", tells the story of the wife and daughter of the most well-known terrorist in the world, Carlos. The central theme of "The Green Prince" is the unique relationship between a Palestinian informant and his Israeli contact agent.

Where did you come across this story?

Schirman: I was looking for a film for my trilogy when a friend told me about Mosab Hassan Yousef's autobiography: "Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable Choices". I devoured it in only two hours and was fascinated by his perspective as an insider and son of one of the founders and leaders of Hamas. I realised that apart from a few headlines in the press, we know almost nothing about Hamas, who are, after all, our neighbours.

How did you make contact with Mosab and convince him to take part in the film?

Schirman: I made contact with him through the former Israeli intelligence officer Gonen Ben Itzhak, whom I met in a café in Tel Aviv. It was the first time that I had met an agent from Israel's domestic secret service. Gonen surprised me.

In what way? What kind of a person is he?

Schirman: I expected to meet a "tough" guy. But Gonen is quietly spoken; he immediately gains one's sympathy and trust. This is perhaps why he is successful. In Yiddish one would say, he is a Mentsh, a person with a good heart. Intelligence work was very complicated for him because it brought him time and again into conflict with his moral values. However, together with Mosab, he had to prevent acts of terrorism.

This was the first time that Gonen had spoken in public. In any case, there was a chemistry between us; we talked for hours. The more he described his unique relationship with Mosab, the more I got goosebumps. That's how I react when I discover an emotional truth. It was very important that Gonen took part because it meant that Mosab trusted me.

How was your first meeting with Mosab?

Schirman: Because I live in Frankfurt and he lives in Los Angeles, we met in the middle, in New York. That evening, while I was waiting in the hotel lobby, the news broke that Osama bin Laden had been killed. Two minutes later, Mosab arrived. He had heard the news on his way from the airport and said immediately: "Come on, let's go to Ground Zero." When we arrived, there were thousands of Americans there shouting, "America! America!" as if the USA has just won the World Cup. Mosab wanted to take part in this celebration because the USA had granted him asylum and thus saved his life. I looked at him and immediately realised how big his identity crisis was: ten years previously, he would probably have been on the other side.

What role did Mosab's conversion to Christianity play? Did this influence his decision to work for the Israelis?

Schirman: His conversion came much later. When Mosab decided to work for Israel, it was very complicated for him. He couldn't go to a psychologist and talk about it, so he had to work it out for himself. I think that when he read the Sermon on the Mount where it says "love your enemy", it made a lot of sense to him. He adopted these teachings as a spiritual guide. Today he is a very spiritual young man who studies and practices yoga. His collaboration with Israel broadened his horizons; after all, he grew up in a radical Muslim group where he had been blinkered.

As a viewer, one has the feeling that the camera accompanied Mosab before and during his work as an informant. How did you manage to create this impression?

Schirman: We wanted to make a thrilling film. And we were very lucky to find rare footage, such as the scenes that show Mosab in Ramallah when he was still working undercover. His father Hassan Yousef was a well-known politician in the West Bank, so Arab TV channels reported on his speeches. But they couldn't understand why of all things we were so interested in totally unimportant sequences showing Yousef being driven by his son. In the dramatic context of the film, these scenes are like dynamite. We also received drone footage from the Israeli military.

Why do you put the two of them directly in front of the camera in separate, bare rooms, as if it was an interrogation?

Schirman: These rooms, which we built in Munich, had five-metre-high concrete walls. They remind us of the walls of interrogation rooms used by the secret police, the wall in the West Bank and the isolation of both men in their own society.

Mosab lives in the USA. Is he at risk?

Schirman: He hides in public. He uses a false name only when he travels. When I met him in New York for the first time, he always sat with his back to the wall and his eyes fixed on the door. Every few hours we had to change location. Today it's more laid-back.

When we shot with Mosab in Germany, we had to be very discreet about his travel and accommodation plans. We also had security guards on set for the first part of the shoot.

When we shot in Ramallah, he didn't come for security reasons. We had to maintain a very low profile, which was difficult with an international crew that included Israelis. But it also brought with it a certain tension, which made us understand better the view of our protagonists.

How did the encounter with these two people influence your life?

Schirman: This special relationship between Gonen and Mosab was only possible because both of them took a great risk in order to do the right thing. Both tend to be very moral and are not afraid to swim against the tide. Both are a complete exception in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, in which most people simply follow instead of leading, and where nobody risks trusting the other. For this reason, Gonen and Mosab's friendship gives me hope.

Interview conducted by Igal Avidan

© Qantara.de 2014