Turkey's "Idol" for prayer callers

Ever since the early days of Islam, the call to prayer has been an integral part of religious practice. The very first muezzin, Bilal, a freed slave of Ethiopian origin, is said to have possessed a powerful resounding voice. Bilal called early believers on the streets of Mecca to prayer five times a day. And the ritual lived on: traditionally, the ezan is supposed to be recited in a beautiful voice, so that people – touched by the melody – will make their way as quickly as possible to the mosque.

Accordingly, the ezan is not a mere means to a religious end, but also an art form in its own right, the performance of which calls for special talent. While muezzins used to mount the minarets of the mosques to call people to prayer, today the call usually issues from loudspeakers in the streets and squares of cities and villages.

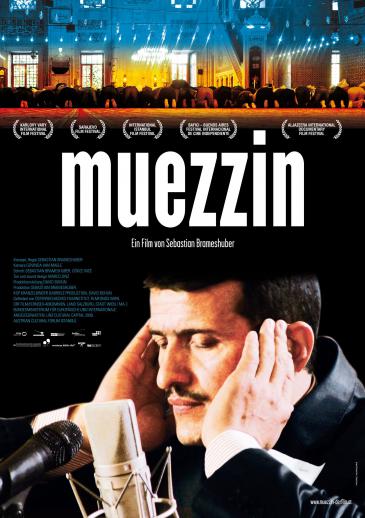

Even though not all prayer callers in Turkey can be said to possess a special gift, the major historic mosques on the Bosporus select their muezzins with the greatest of care. We get a glimpse of their world in the documentary "Muezzin" by Sebastian Brameshuber, who did his research in Istanbul's grand houses of prayer.

Vocal polyphony

The Austrian film director portrays two Istanbul muezzins who compete in the national muezzin competition, a kind of "Pop Idol" for prayer callers. The best voices in Turkey vie year after year for the title of the country's most gifted muezzin.

Although the call to prayer rings out through the streets of Istanbul from nearly 3,000 mosques, the muezzins are practically invisible. People listen to them and everyone has his or her favourite voice, but hardly anyone has actually come face-to-face with a muezzin.

On his first visit to Istanbul, Brameshuber was fascinated by the vocal polyphony that can be heard at prayer times. Then he learned of the national competition while talking with a muezzin. It would form the subject for his first documentary.

Insights into the lives of the muezzins

In "Muezzin" Brameshuber not only manages to provide us with authentic insights into the art of prayer-calling, but also into the lives and thinking of the muezzins. We meet Halit Aslan, who came to Istanbul from Eastern Anatolia. Aslan is shown having breakfast on the balcony with his two sons, pushing bread and cheese into their mouths as he describes why he enjoys living in Istanbul.

The city is the centre for prayer callers, he says, so there are better career opportunities for a good muezzin. Aslan is also proud to live nearby the grave of the "Fatih", the conqueror of Istanbul, who is buried on the European side of town.

Viewers then learn from Mustafa Yaman, winner of the last competition, that the singing of the ezan, which is recited in Turkey within the classical makam scale, is closely related to the secular art of singing. "If I hadn't gone to religious school, I would probably have become a singer," reflects Yaman, pointing proudly to a newspaper article about his victory last year.

Isa Aydin, a muezzin from a suburban mosque who is keen to impress the jury with his high-pitched voice, philosophises about the muezzinʹs reputation and vocation: "I always ask myself whether my ezan is good enough to motivate someone to pray. The more people a muezzin can entice into the mosque, the more successful he is."

Milieu study of a key aspect of Turkish society

The deeper the documentary penetrates into the world view of the muezzins, the more music becomes secondary as Brameshuber's film evolves into a milieu study of a key aspect of Turkish society.

In the kitchen of Habil Ondes, undisputed master of the prayer call and the much-feared head of the muezzin jury, several women busily bustle about so that Ondes can be served his dinner. Brameshuber appears to have selected such scenes out of over 150 hours of film footage in order to highlight the conservative customs of his subjects.

The guilelessness of the muezzins' preparations in their effort to convince the jury appears refreshingly down-to-earth by contrast. The men regularly drink milk with honey to achieve the perfect voice and they diligently rehearse their calls. At the competition, which takes place in a mosque before a male audience, the candidates perspire and tremble in eager anticipation of their turn to sing.

The brothers in faith, dressed up in their finest suits, now become fierce rivals. When Isa Aydin ultimately wins the honour of representing Istanbul in the national contest, Halit Aslan is irked. He evidently begrudges his adversary his victory and complains that higher and higher voices are being favoured over the lower ones.

Brameshuber says of his film: "I came to know my protagonists as very pragmatic men who pursue their work with passion, but speak more of the musical than of the spiritual aspects."

By the end of the film, we are able to associate the sometimes otherworldly-seeming ezan calls that can be heard resounding from the mosques with real flesh-and-blood people who long for recognition and success and who with their naive earnestness sometimes summon a smile to our lips. This portrayal of the Turkish muezzins with all their ambitions and cares presents the entirely human face of Turkish Islam.

Marian Brehmer

© Qantara.de 2018

Translated from the German by Jennifer Taylor