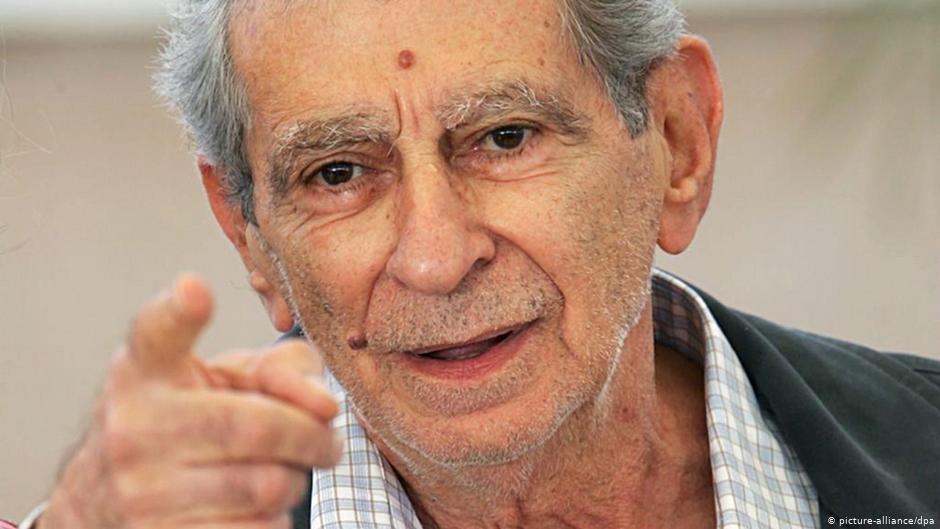

The great visionary of Arab cinema

Almost exactly 50 years ago, a limping newspaper boy could be seen hanging around the concourse of Cairo Central Station. He was new to the city: behind him, his village; before him, pin-up girls. The walls of his wooden shack were papered with their images. But these scantily-clad women would be of little help to him, a young man suffering the pangs of unrequited love for the drink-vendor Hanouma. Qinawi is the name of the hapless main character in "Bab al-Hadid" (Cairo Station, 1958), who was played by the director himself, Youssef Chahine.

Arsenal, the Institute for Film and Video Art in Berlin, recently paid tribute to the father of Egyptian – nay Arab – cinema by devoting a retrospective to his work. Not all of Chahine's 44 films were good in the cinematic sense, but they are all vivid snapshots of contemporary Egyptian history. And this is what makes the complete oeuvre of this passionate film-maker, who passed away in 2008, so valuable today.

"A man possessed"

"Chahine was a man possessed," says Marianne Khoury. "There was only a very thin line between cinema and his private life. Everything was interwoven – even his family." Khoury knows what she is talking about. Not only is she a producer and film-maker, she is also Chahine's niece. Being part of his creations, she says, was like joining a cult.

Youssef Chahine was fiercely independent. Throughout his life, he hated nothing more than people trying to talk him into doing things. This is reflected in the subject matter of his films: right from the word go, he highlighted the conflicts between the common people and representatives of state or the upper class.

Many of his characters suffer from sexual frustration, which becomes a breeding ground for brutality in the precarious existence that is life in a big city or in the face of police repression. Several of his films can be interpreted as foreseeing the strikes that began to grip the Egyptian textile industry from 2007 onwards and that ultimately led to the revolution in 2011.

"Alexandria … why?"

Indeed labour rights are a frequent theme in Chahine's work. In a highly amusing scene in "Iskindereya… leh?" (Alexandria … why?, 1978) a young man asks his wealthy father for five pounds. "Five pounds?" replies his father. "That's the wages of five workers!" His son retorts: "but they are underpaid", to which his father replies: "So, the boy thinks he's a communist."

In the end, of course, he gives his son the money. He certainly won't miss five pounds. "Alexandria … why?" won the silver bear at the Berlinale in 1979. This cemented Chahine's global fame once and for all.

International recognition was always very important to him. That is why he was accused of always having one eye on France or the United States and of being indifferent at heart to the Egyptian masses. In light of the themes addressed in his films, this accusation overshoots the mark.

Nasser's poodle?

The criticism that he at times allowed himself to be used by Gamal Abdel Nasser – president of Egypt from 1954 to 1970 and adored by the Egyptian people – for the latterʹs own ends, is more accurate: the film "Al Nil wal Haya" (Once Upon a Time … The Nile, 1969) was a co-production between the United Arab Republic and the Soviet Union and was commissioned by Nasser himself.

Nevertheless, Youssef Chahine remained independent to the core. His vision of cinema was too personal and too uncompromising to allow himself to be used by anyone in the long term, write the curators of the Arsenal retrospective in the accompanying leaflet.

The first version of "Once Upon a Time … The Nile" didn't meet with the approval of the film's soviet bankrollers. In the years that followed, several of Chahine's films were censored. To this day, some of them are banned in a number of Arab countries. This is one of the reasons Chahine set up his own production company, Misr International, in the early 1970s. The company is now run by his niece, Marianne Khoury. This gave the director, whose work matured as he grew older, greater artistic freedom.

Parody of mainstream cinema

"Only a handful of Arab directors have made such a transition from mainstream film-maker to committed film auteur," says film theorist Viola Shafik of the work of the Egyptian director. His film style, she says, parodies mainstream cinema, while at the same time incorporating elements of it. "With regard to this hybrid style, he can certainly be compared with Federico Fellini," says Shafik. Fellini is considered one of the greatest film auteurs of the twentieth century.

It is above all the artistic freedom in Chahine's work that makes him a lodestar for today's Arab film-makers. In this respect, the Zawya cinema in Cairo – perhaps the first and only arthouse cinema in Egypt – has played a massive role as a cinematic hub since its establishment in 2014. Zawya shows films by both great directors such as Chahine and lesser-known independent film-makers.

Since the early days of digitalisation in the mid Noughties, independent films have been produced in Egypt. Suddenly, it has become easier and cheaper for young directors to make films. "This development has brought great movement into the film scene. However, all of this is happening in parallel to the mainstream film industry," says Viola Shafik. In other words, most of these film-makers are cut off from the funding opportunities within the country. More so than in other parts of the world, Arab film-makers depend on foreign financial backers, who often dictate the subject matter of the film.

Bridges between West and East

One of Youssef Chahine's last films was "Al-Massir" (Destiny, 1997). In this historical film, which was untypical for him because of its formulaic quality, he used the twelfth-century philosopher Averroes to show how quickly liberal thinking can come under threat from intolerance and hate.

"He wanted to build bridges, between West and East too," says Marianne Khoury. This unifying aspect was the born of Chahine's biography. His father was Lebanese, his mother Greek. Muslims, Jews and Christians (the Chahines were the latter) lived quite peacefully alongside each other. His native city, Alexandria, was considered cosmopolitan.

Youssef Chahine, this great Arab director, stands – and has always stood – for open-mindedness and tolerance. For example, at a very early stage in his career, he addressed the issue of homosexuality in his work. To this day, it is still a taboo subject in Egypt and in many states in the region.

Whether there will be any room in Arab societies for the plurality of identities shown in Chahine's work is the big question. It is not unusual for film-makers to be before their time. Real life may, however, catch up.

Christoph Resch

© Qantara.de 2019

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan