Dynamite for Social Relations

In February 1933, the Egyptian daily newspaper al-Ahram published a series of articles about the rise of National Socialism in Germany. The articles appeared on the front page, surrounded by pictures of the birthday of the Egyptian crown prince, Faruq, or the Turkish beauty queen's visit to Cairo.

The Egyptian public was well informed about events in Europe in the 1920s and 30s. Various daily newspapers and magazines published reports about technical inventions and scientific innovations in Paris, Berlin or Rome as well as features on the latest trends in fashion and art.

This familiarity with European matters was also reflected in the commentaries on political developments in Europe. The rise of Fascism and National Socialism were just as widely discussed in Egypt as the October Revolution in Russia and the Civil War in Spain.

Colossal social upheaval

During the inter-war period, Egypt too was re-shaping its social order. Since the 1919 revolt against the British colonial power and the formal recognition of the independence of the country in 1922, the Egyptian people had been going through a period of political pluralism in which the self-image of the country was just as much a subject of debate as the rights and obligations of the individual to the community, the relationship between religion and politics and the role of women in society.

With the emergence of movements such as the nationalistic Wafd, the Muslim Brotherhood, and later Young Egypt, Egypt soon had a political landscape as diverse as that in Europe. Many observers considered the political models and movements in Europe to be possible points of reference in the debates about the new social structures that Egypt still had to create.

As early as the 1920s, intellectuals like Muhammad Husayn Haykal, Taha Husayn, or Abbas Mahmud al-Aqqad, who largely shaped the debates in the days of the "liberal experiment" (Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid Marsot), made specific references to the experiences of parliamentary democracies in Europe. Nevertheless, their stances on the matter varied greatly.

While authors like Husayn and al-Aqqad used their renown to campaign for the Egyptian constitution of 1923 in the light of the rise of Fascism in Italy, Haykal spoke again and again of Mussolini's success in stabilising Italy during the crises that had occurred since the First World War.

At the heart of Haykal's argument was a warning against social anarchy, which he combined with a sharp criticism of the Egyptian royal family and Britain's continuing influence in the country. The elitist liberalism favoured by Haykal was not, in his view, the same as a parliamentary democracy based on the European model.

Despite his defence of the constitution, he feared that the demands of the nationalistically-oriented Wafd party and other players who favoured comprehensive political rights, would lead to a tyranny of the streets. He spoke out in favour of the introduction of a "reform dictatorship" for a transition period during which the population would be prepared for democracy. This dictatorship, he felt, could base itself on Italy's experiences.

Defence of democracy

In his book Absolute Rule in the Twentieth Century, on the other hand, Abbas Mahmud al-Aqqad roundly opposed any justification of authoritarian systems, even a passing one. In doing so, he was going against the opinion that democratic societies in Europe had not succeeded in mastering social crises.

"Democracy has not failed and so far everything points to its success," he wrote in response to those who claimed that the end of the age of democracy was nigh. "Everything points to the fact that democracy is stable and that it will in future be the basis of all rule, that its principles will be referred to by governments, and invoked for all upcoming reforms." As far as al-Aqqad was concerned, this applied to Europe and no less to Egypt too.

He considered the 1919 revolution to be the foundation of a democratic social order in which the rights of the individual were guaranteed even in the face of the claims of the community. He also felt that these achievements had to be defended against advocates of authoritarian orders such as those in Italy and Russia.

It was noticeable that these rebukes established a relationship between Fascism and National Socialism and developments in Egypt itself. In this respect, the debates about Fascism and the crisis experienced by the Weimar Republic in the early 1930s were clearly shaped by the authoritarian policies of Ismail Sidqi's government.

The suspension of the constitution and the widespread oppression orchestrated by Sidqi between 1930 and 1933 seemed to mirror events in Europe. At this time, any criticism of Mussolini and Hitler was also a criticism of the political situation in Egypt.

The discussions about nationalist ideologies that gained importance in Fascist Italy and later in National Socialist Germany were also shaped by circumstances in Egypt itself. The question as to the basic principles of the Egyptian nation occupied the minds of people like hardly any other.

Morality and eugenics

In addition to Islam and the Arabic language, the country's Pharaonic heritage offered a possible point of reference for the attempts to shape the collective identity of the country. The concept of race also played a role in this context. Salama Musa, for example, a major advocate of socialist ideas, pointed to biologistic teachings. As far as he was concerned, eugenic racial policies, such as those pursued by National Socialism, offered starting points for similar measures in Egypt.

"A modern society," claimed Musa in a pamphlet published in the mid 1930s, requires "a high degree of intelligence and morality. The nation that amasses the most intelligence is destined to be superior to others. For this reason, no nation can afford to ignore eugenics and to allow idiots, criminals, and the inferior to procreate."

This is evidence of the fact that National Socialism was certainly not alone with its policies. Musa found similar approaches in the USA, Sweden and Switzerland.

Criticism of German anti-Semitism

But biologistic theories of this kind were rejected by many observers. Members of ethnic and religious minorities in particular and also liberal nationalists were concerned about any attempts to define affiliation to the nation by means of categories such as race and ethnic group. Commentaries in newspapers and magazines, which were often published by Christians with Syrian roots, were correspondingly critical. In this context, Germany's anti-Semitic policy met with particularly harsh criticism.

Even in early 1933, dailies like al-Muqattam, which was one of the leading newspapers in the country, were issuing clear warnings about anti-Jewish policies.

In July 1933, the monthly newspaper al-Hilal, which was also owned by Syrian–Lebanese immigrants, specifically warned that it was the business of the state to protect the interests of all its citizens. "It is the duty of all civilised states to cherish all its citizens in the same way and to protect them without discrimination regardless of the religious community to which they belong."

National Socialist racial theories – and biologistic thought in general – were, as far as these writers were concerned, dynamite for social relations in view of the ethnic and religious make-up of the Egyptian population.

Advance warning of expansionism

Egyptian interest in developments in Europe peaked again with the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in October 1935. In view of the thinly veiled territorial ambitions of Italy and Germany, many critics of both regimes felt that their warnings had been justified by events. Seen from this viewpoint, Germany's policy towards its neighbours and the League of Nations were advance warnings of its expansionism, which was hardly any different from that of other European colonial powers.

Ultimately for many observers, the brutality with which Italy treated the indigenous populations in Libya and Abyssinia was reason enough to call for British and French support against possible Italian designs on Egypt. The colonial policies of these two states seemed to them to be the lesser of two evils when compared to the advances of Italy and Germany.

The inter-war period was characterised by such political and intellectual encounters with Europe. These disputes developed against the backdrop of social upheaval in Egyptian society. Many observers believed that Fascism and National Socialism did contain teachings on which Egypt could also build. No less prominent, however, were the voices that emphatically warned against the influence of Fascist and National Socialist ideologies.

As far as this latter group was concerned, an authoritarian order was not a solution to the conflicts that characterised the political system in Egypt at the time, and more political freedom – not less – was necessary if democracy was to be secured in the long term.

Götz Nordbruch

© Qantara.de 2011

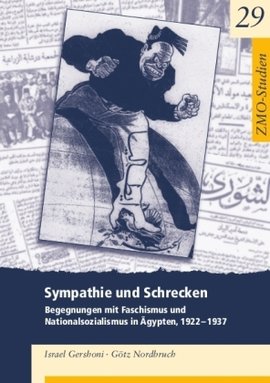

Götz Nordbruch is assistant professor at the Centre for Contemporary Middle East Studies at the University of Southern Denmark. He is the author of Nazism in Syria and Lebanon: the ambivalence of the German option, 1933-1945 (SOAS/Routledge studies on the Middle East: 2009) and co-author of the newly published 'Sympathie und Schrecken – Begegnungen mit Faschismus und Nationalsozialismus in Ägypten, 1922–1937' ("Sympathie and Horror – Encounters with Fascism and National Socialism in Egypt, 1922–1937", ZMO-Studien 2011).

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de