"What next? Will we ask Muslims to kneel?"

Right now, there is one subject on which the French and their unpopular president agree: the barbarism of the jihadists is not acceptable. Since the brutal advance of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, politicians of all hues, religious officials and men and women on the street have all been voicing their indignation.

For weeks now, the political magazines have been running major stories on the "new masters of terror" ("Nouvel Observateur"). Fear is spreading. You would almost think the IS fighters were just about to take control of the Eiffel Tower. The enemy of an entire society has been identified: radical Islam and its brutal warriors.

Dealing with the situation is not made any easier by the interior minister's information that some 900 French citizens – including many young people – have joined the jihadi fighters in Syria and Iraq. These young people are no longer being recruited solely from among marginalised groups in the banlieues; many of them are the children of middle-class families; some of them don't even have a Muslim background.

"France must know that it is protected, that it is safe." Those were President Francois Hollande's big words on 19 September, when he informed his compatriots of the first aerial attacks by Rafale jets on Islamic State positions in Iraq. The battle against terrorism harbours security risks, he acknowledged, but was also an important and great matter. Polls show that Hollande has the political trust of only 15 per cent of his country's 65 million inhabitants. France's involvement in the military campaign against IS in Iraq, however, is a popular move: according to an Ifop survey for the weekly newspaper "Journal du Dimanche", one in two French voters supports it.

"Kill them in any way possible"

Following Hollande's de-facto declaration of war, IS began making open threats. Abu Mohammed al-Adnani, the group's spokesman, issued a call to all supporters: "If you can kill an American or European infidel – especially the spiteful and filthy French – then rely on Allah and kill them in any way possible." Only days later, the "Soldiers of the Caliphate" in Algeria, a group loyal to IS, beheaded the French mountain guide Herve Gourdel in the Kabylie region. All of France reacted with an outcry of horror.

Many of the country's approximately four million Muslims feel obliged to voice a clear opinion. The major Muslim organisations such as the French Council of the Muslim Faith (CFCM), the Union of Islamic Organisations of France (UOIF) and the Union of Mosques in France (UMF) instantly launched protest rallies against Islamic State barbarism.

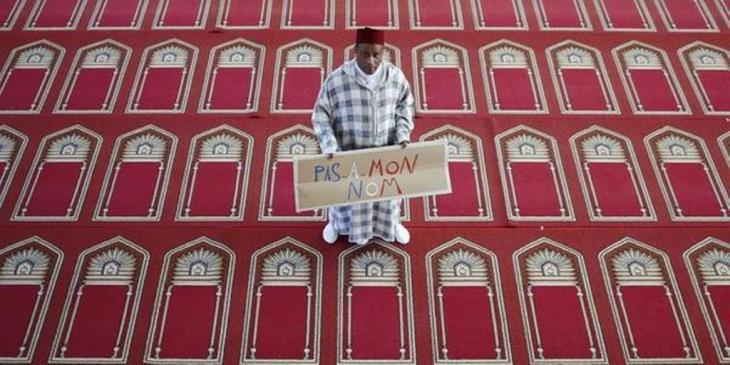

A number of prominent Muslims published a joint statement in the conservative daily newspaper "Le Figaro" entitled "We too are filthy French". Numerous French Muslims joined in the Twitter campaign, adapted from a British initiative, #PasEnMonNom (Not in my name), posting statements such as "The terrorists don't belong to us" or "Muslims, awaken! We can't stand by and look away any longer."

That was not enough for the online edition of "Le Figaro", which is usually critical of Islam. On the day after Gourdel's murder, the question of the day on its website was: "Do you think the condemnation by French Muslims has been sufficient?"

That brought a tidal wave of anger in the social media, with figaro.fr later withdrawing the question. Since then, a controversial debate has been raging in France, focusing on two key issues: should Muslims have to take a public stance on this matter? Or is such an expectation implicit evidence of a general suspicion towards a whole section of the population, just because they are of Islamic faith?

The Muslim newspaper "Saphir News" was up in arms: "Why should Muslims raise their voices against extremists to whom they have no connection and for whose deeds they are in no way responsible?" The Collective against Islamophobia in France (CCIF) has also distanced itself from calls for demonstrations. Its statement: "Muslims should not play along with this Islamophobic game. It consists of always presenting them as guilty parties or ideal suspects and thereby constantly expecting them to justify themselves for the actions of others."

For the same reason, the CCIF also criticises the Twitter campaign #NotInMYName/PasEnMonNom. The organisation's website features a background photo of a Buddhist monk, with the question: "Do I have to apologise for the genocide of the Rohingya in Burma?"

Muslims apologise …

A new Twitter hashtag soon emerged: #lesmusulmanss'excusent (Muslims apologise). Tweets poke fun at statements distancing themselves from the IS jihadists by means of ridiculous apologies along the lines of "Muslims apologise for the disappearance of the coral reefs on the Maldives" or "Muslims apologise for rain in July". Several left-wing media outlets have reacted similarly. In a comment piece, the newspaper "Libération" asked: "What next? Will we ask Muslims to kneel? Or to go to war against IS?"

Mohammed Moussaoui is the president of the UMF, an organisation of 500 prayer houses. He declared that it was essential for French Muslims to continue their vocal campaign against terrorism. Silence was only grist to the mill of those who consider Muslim reactions nothing but empty words, wrote Moussaoui on the Internet platform Oumma.com. Another reason, he added, was to send a clear message to the terrorists that their barbarism does not have the support of French Muslims. This could also help keep young French people from joining up to the so-called "jihad of Daesh" (the IS jihad).

Numerous imams in France are asking themselves how they can reach these young people, most of whom become radicalised with the aid of the Internet. Part of the problem is that they don't set foot inside the mosques.

Olivier Roy, an Islam expert and professor at the European University Institute in Florence, speaks of a wave of nihilism affecting young people lost in globalisation and now fascinated by death. This, he says, is a phenomenon that goes beyond the Muslim faith.

All al-Qaida or Islamic State offers these young people is a territory in which they can live out this nihilism and which gets them in the headlines at the same time, he explains. It would be wiser to reduce the IS jihad and jihadists to their actual size, Roy advises, instead of raising the flag and calling upon the nation to unite in battle against the threat.

Competition for most spectacular jihad stories

The very opposite is happening in France at the moment. Not only are the national media vying for the most spectacular headlines on jihad, many politicians want to exploit the subject for their own ends too, especially the right wing. Front National head Marine Le Pen has issued warnings against returnees from Syria and Iraq, "who are prepared to carry out acts of barbarism in our country in the name of jihad."

The conservative UMP ex-minister Xavier Bertrand has referred to the returnees as domestic enemies and called for the presumption of innocence to be disregarded in their cases, assuming instead their guilt and giving the justice system special powers. "It's a question of them or us," he said.

Words like these will not help to reduce France's already marked Islamophobia. Conversations in cafés and marketplaces indicate that scepticism towards Muslims is on the rise. No matter how hard they try to be on the right side and do the right thing in this tense situation, in all probability they will be among the losers in this battle against jihadi terrorism.

Birgit Kaspar

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire