'The idea of male dominance is in crisis'

Ms Oussedik, you have conducted research into changes in family structures in Algeria. What do you see as the principal drivers of this change?

Fatma Oussedik: It is important for me to emphasise that we are a society in flux, because all too often people project onto Arab societies the notion that we are inflexible. My research in the three cities of Algiers, Oran and Annaba was part of a larger study involving qualitative surveys of 1,200 families in all cities, which we then supplemented with in-depth interviews.

The most significant factor driving change is rapid urbanisation. In the 1960s and 70s, the majority of the population still lived in rural areas. Today, 70 per cent of Algerians live in cities, mainly in the north of the country.

Another factor is education. Today, 98 per cent of children – boys and girls – attend primary school, and 70 per cent of university students are female. This is a global trend that we observe across all faculties.

The act of moving from the countryside to the city, leaving the extended family home and finding an apartment for the nuclear family, establishing and maintaining connections outside the country, for example through travel – all these things have profoundly changed the lives of Algerian men and women.

Urbanisation has significantly altered the size of families and the status of individual family members. In the Algeria of today, all girls go to school, and their educational qualifications are important to them.

Even though the proportion of women in work is still very low – currently around 20 per cent – in my interviews, these women no longer describe themselves as housewives, but as unemployed. They are conscious of their qualifications, although the economic situation makes it hard for them to find a position.

Education and income change everything

What changes when women are in employment?

Oussedik: Women who find jobs have money at their disposal, and this fundamentally changes their status. They then have a say in how the family spends its money and can influence their children's education. Women look after elderly parents and, increasingly, they are the ones who make the economic decisions in a family; they determine the paths of the children's schooling and make consumer decisions.

However, the management of assets is still the preserve of men. Land and cars usually belong to the men, and this often causes big problems when it comes to divorce. Women who have worked their whole lives may still find themselves penniless after a divorce, even if the position of women in the family has changed considerably.

So it's primarily economic factors that are driving changes?

Oussedik: Not only these. Knowledge acquired through education is key – as is money. In a patriarchal system of the kind we see in Mediterranean societies, it's the paterfamilias who represents the family in external matters and makes all the important decisions. But with the unemployment and economic difficulties we are facing today, men are losing a lot of their power in the family.

This undermines traditional masculinity, whereas women have been able to create greater freedom for themselves, especially if they earn money. Traditionally, a man's role was to provide for the family and defend it against the outside world, while women were expected to bear children. Today, the average number of children born to Algerian women has decreased, while the age at which they marry has gone up.

Today, on average, women in Algeria marry at 30, men at 35. Another new aspect is that, since about the year 2000, there are women in Algeria who don't get married at all: about six per cent. They live alone, make their own decisions, participate in social movements, and travel – alone or in groups. We can see from this how much ideas about gender roles are changing.

Women are buying their way out of marriage

Please give us another example of these changes.

Oussedik: We see the changes when it comes to divorce, for example. According to the Islamic understanding of divorce, it was more or less impossible in the past for women to get divorced. Only men were able to repudiate their wives; this form of divorce is still the most common in Algeria.

However, it is closely followed by so-called Khol' divorces. These grant women the right to dissolve a marriage. In return, they must give up their financial claims. You could say that with a Khol' divorce, a woman buys her freedom.

Women very often avail themselves of this possibility, and this is also having a visible impact on society. In 1988, when I conducted a survey about it, the idea still prevailed that men occupied the public space while women stayed in the private realm.

Back then, only about 10 per cent of women worked – far fewer than today – and only really in three professions. They were teachers, healthcare workers or worked in administrative roles, all professions in which they were not visible to the general public. Today, if you come to Algiers, you'll find waitresses everywhere in the bars in the city centre, and there are no post office or bank counters without female tellers. Women are represented everywhere.

Does that also affect how marriages are contracted today? Do arranged marriages still take place?

Oussedik: Today, university, the labour market and, above all, Facebook are the principal marriage markets. When I ask young people if their parents chose their partner for them, I usually get the reply: "no, we met on Facebook and then met up in secret."

The idea of marriage in the olden days, when the woman met her future husband for the first time on the day of the wedding, requires some demystification. Even in those days, women usually did find ways of meeting their future spouses. Nowadays, though, we even have couples who live together without being married.

In my research, I pay close attention to small signs of change – details that are not yet statistically measurable, but that indicate the direction in which a society is heading.

One such a change is women who live alone long-term – although this only happens in certain, more affluent neighbourhoods in the big cities, which accept single women living alone like this. It is still not possible in Algeria's rural regions. We are seeing this development in other Arab countries, too.

"The headscarf is losing its religious edge"

Moroccan sociologist Fatima Sadiqi believes that women's movements in North Africa have changed over the past ten years. Today, women from all social classes are fighting together for more rights, regardless of whether they are "secular" or "Islamic" feminists. Claudia Mende spoke with her for Qantara.de

Between family law and social reality

Nonetheless, family law in Algeria still designates the man as the head of the family. Doesn't that lead to considerable tensions?

Oussedik: Yes. These changes are taking place within a sort of legal straitjacket that still puts great restrictions on women's freedom. Family law does not reflect social reality; the contradictions are huge. Family law in Algeria still sees the man as the head of the family.

Algerian women's movements – there are a great many women's organisations in Algeria, including in rural areas – have managed to push through some changes to family law, such as recognition of Khol' divorces.

But there are two factors that hinder fundamental reforms. One is the contradiction between social reality and the law, and the difficult situation on the job market, especially for women.

If there were more jobs for women, change would happen faster – because having an income of their own is the key factor. Once women have money of their own, it changes their expectations of relationships and their possibilities for living an autonomous life.

Women take advantage of new opportunities

If the social reality continues to change, might the legal aspect eventually only exist on paper?

Oussedik: Exactly – because the law is an expression of certain power dynamics in a society. I am a feminist, and I am convinced that history is moving in our favour. We've seen this in education, and it will be the same with the job market. When women have new opportunities, they take advantage of them.

That's also why I'm not opposed to the burkini, which a French journalist once asked me about. For me, what's important is that women go to the beach – that's the decisive point, whether they do so in a burkini or a bikini. Nowadays women go to the beach in droves, and this is good news.

When opportunities are there, women seize them: that's what's crucial. The patriarchy reveals itself in different societies in different ways; it looks different, depending on the socio-economic context, and women make use of their respective opportunities to create new freedoms for themselves.

Arab feminism has a context of its own

So where do you see the difference between Western and Arab feminism?

Oussedik: Feminism is universal, but it manifests itself differently depending on the context in which it is lived. We fight differently to Western women, because we're dealing with different conditions. The patriarchy expresses itself differently where we are. I define myself as an Algerian feminist, a woman who fights within the social and historical context of Algeria and within a specific legal, cultural and religious value system.

Are cultural norms also changing, such as the idea that women should not have sex before marriage?

Oussedik: If a woman has had sex before marriage, there is now the possibility of hymen reconstruction, and this medical procedure has become far more common throughout the Arab world. This is another new possibility for women. Virginity prior to marriage is still the ideal, but more and more women are undergoing hymen reconstructions.

I see this as a way for women to liberate themselves from this ideal. For men, it means that the value of an intact hymen can no longer be prized as highly when it is known that it can be medically reconstructed at any time.

Conservative family values alongside change

So you see conservative family values and laws in society, and also, at the same time, tremendous change?

Oussedik: Men need the legal system, which conveys a traditional idea of family with the man at its head because at the moment, they are losing their status in our society. What they are left with is the idea that they have an elevated status within the family. A whole ideological system reinforces this idea for them, but for some time now the social reality has been very different. The idea of male dominance is in serious crisis.

Basically, these are processes of individualisation. In your book you write that this development also contributed to the Hirak protest movement. In what way?

Oussedik: During the Hirak protests, people from all walks of life came together: all age groups, both sexes, people from villages and from cities. Islamists were shouting their slogans alongside feminists, and it was all done peacefully. For me, that was an indication that Algerians know how diverse they are. They realise that they are individuals with differing political views, but still united by a common goal. That is an important development in our country.

Interview conducted by Claudia Mende.

© Qantara.de 2023

Translated from the German by Charlotte Collins

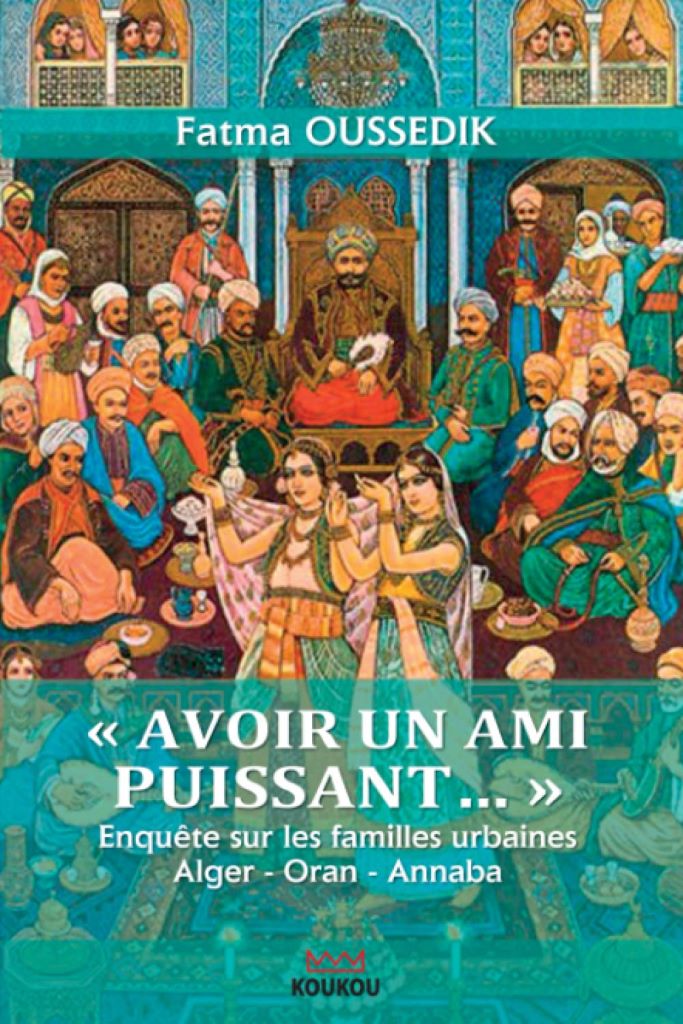

Fatma Oussedik studied sociology at the University of Algiers, and gained her PhD from the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium before being awarded a professorship in sociology at the University of Algiers. Her latest book, Avoir un ami puissant: Enquête sur les familles urbaines Alger-Oran-Annaba, was published by Editions Koukou in Algiers in 2022.