Arab Spring and October Revolution

The demonstration against the presence of U.S. troops in Iraq wasn't attended by a million people, but thousands. Protesters marched along the left bank of the Tigris as far as the entrance to Baghdad University. The Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr had issued calls for a "million-man march".

"Americans out of my country" was one of the slogans on the protesters' banners. The killing of the Iranian General Qassem Soleimani on 3 January at Baghdad airport by an American drone had in any case further stoked anti-U.S. sentiment in Iraq. Whereas previously, resentment concerning foreign influence in Iraq had been aimed primarily at Iran, now that criticism is being levelled at the United States. The Iraqis fear that they are increasingly finding themselves between the frontlines of the Washington-Tehran conflict and that they are being crushed in the process.

All means are currently being deployed to break the protest movement in Iraq. Abductions, the targeted killings of activists, threats against their families, raids of their homes. Journalists who report on the protests are harassed and detained, the studios of opposition TV studios are destroyed and equipment rendered useless. The most recent example of such repressive measures is the abduction of four staff at a French, Christian NGO in Baghdad – three French citizens and one Iraqi.

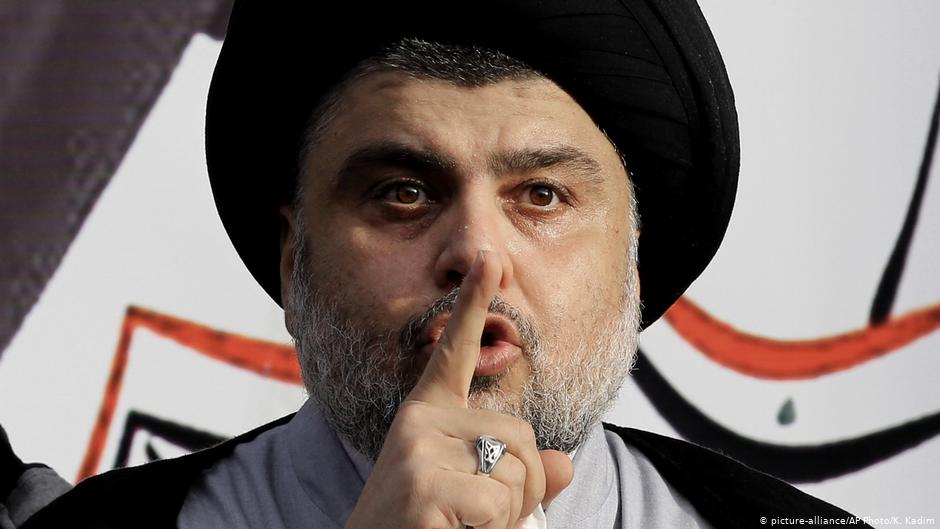

The divisive figure of Muqtada al-Sadr

Muqtada al-Sadr's million-man march was also aimed at weakening the movement by dividing it. Whereas the cleric placed himself at the helm of the movement when the demonstrations began in October and supported their aims, he is now seen as a divisive force.

Al-Sadr is no longer saying that all foreign troops should leave Iraq, in line with demands by the people on Tahrir Square in Baghdad. Photos are being circulated showing him alongside Soleimani and the Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. His position is now clear. He has distanced himself from the demonstrators on Tahrir Square, and they from him.

Now the security forces are striking back in brutal fashion, after Sadr terminated his support for the protests. Thirteen people died within 24 hours, the tents on Tahrir Square are burning. Officials are firing live ammunition. They are under orders to break up the protest camp.

The Arabellion moves from Cairo to Baghdad

The four journalists didn't really want to meet at the proposed venue in a side street off Tahrir Square in Cairo. "We have to expect that we could be arrested at any moment," they said. But then they did appear, in Café Riche, where as a student Saddam Hussein drank his tea and gathered with sympathisers of the Ba'ath Party, of which he was the founder and which later brought him to power.

"It was a dream," says Nora and Noor, Alaa and Abdal Galil, what began on 26 January 2011 and became known as the ultimate Arab Spring. An uprising of the young against long-time ruler Hosni Mubarak, "our revolution" as they are still calling it.

They only reluctantly accept that their protest was not a revolution at all, because it didn't change anything, didn't usher in a regime change, didn't alter the system. Sometimes it's difficult to admit the truth. Two women and two men who dare not give their family names because they fear the man who destroyed their "revolution", who promised democracy and brought dictatorship.

Egyptian President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi has ruled with an iron fist for five years, jailing all those who publicly contradict him, tolerating no opposition whatsoever and quashing all those who attempt it. "Worse than Mubarak," the four journalists agree. None of them are allowed to publish anything at the moment.

Early on in the Egyptian uprising, there were also plenty of million-man marches like the one in Baghdad today. The inhabitants of this nation on the Nile took to the streets in their masses. Mubarak stepped down after just two weeks. On this point, the Egyptians have one over the Iraqis. In Baghdad on the other hand, Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi and his government may have officially resigned after eight weeks, but he is stubbornly holding onto power until the next government is formed, something that is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Nora is surprised to hear that the Iraqis have adopted symbols from the Egyptian rebellion: T-shirts with similar slogans and the date that the uprising began, scarves in the national colours, gallows with dolls hanging from them, or photos of individuals the demonstrators want to see the back of. The past enthusiasm of the Egyptians lives on in the Iraqis of today, the hope that they can bring about change, the self-confidence to control their own destiny.

The era of animated discussions, an enormous politicisation of society, genuine dialogue and fruitful exchange has been transported from Cairo to Baghdad. Today in Cairo no one talks about politics anymore, without checking who might be listening or immediately falling silent. "Ali: Fear Eats the Soul", was the title of a 1970s film by Rainer Werner Fassbinder. This is highly pertinent to the current situation on the Nile.

Iraq's "October Revolution"

One thousand three hundred kilometres away from Tahrir Square in Cairo, people stand in the pouring rain and wait. No, an Arab Spring 2.0, as the Egyptians say, is not what's happening in Baghdad and southern Iraq. They call their uprising the October Revolution, because it began on 1 October with the issuing of an ultimatum to the government to stand down, to then start up again three weeks later with twice as much fury, because nothing had happened in the meantime.

Now, Tahrir Square and the streets that surround it are a sea of tents. For months, the protesters blocked traffic on three bridges over the Tigris, occupying half of each of them. Security forces tried in vain on several occasions to battle their way through.

Only after the intervention of the Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, which is dividing the protest movement, did security forces succeed in fighting their way through one of the blocked bridges. They also managed to force occupiers off the expressway to the east of Tahrir Square.

The battles are taking place every day; and every metre counts. Both parties are resorting to harsher means. As far as security forces are concerned, they are no longer just using tear gas and sirens but now also deadly ammunition and snipers. The demonstrators are also using more dangerous weapons. Whereas in the early phase they used rubber slingshots to throw stones and fireworks at their uniformed opponents, there is now an increasing number of Molotov cocktails in evidence. Almost 500 people have now lost their lives in these protest rallies in Iraq.

The same scenario played out in Cairo nine years ago. Bloody battles raged in the side streets off Tahrir Square. Mohammed Mahmoud Street is a case in point. For days, it was the scene of heavy clashes between demonstrators and security forces. The official death toll is 846. A court later found Hosni Mubarak responsible for the loss of life.

Cairo's Tahrir – a place best avoided

In actual fact, say Alaa and Abdal Galil, the number of dead was more than 1,000. Later then, in August 2013, more than 130 people were killed when the Egyptian security offices brutally dispersed a large-scale sit-in on Rabaa al-Adawiya Square in front of the eponymous mosque in support of their ousted President Mohammed Morsi. Responsibility for this massacre lies however with the current president, who was commander of the Egyptian army at the time.

Remarkably, Sisi secured the approval of his compatriots for this brutal action by calling on them to come to Tahrir Square and thereby vote with their feet on whether he should take measures against the Muslim Brotherhood and its "terror", as he called it. People streamed onto the square in their masses, cheering Sisi and singing the national anthem.

Noor's father was subsequently killed on Rabaa al-Adawiya Square; her brother has been imprisoned without trial for months. For Philip Hanna of the Goethe Institute in Cairo, this is one of the reasons why more people are not protesting against Sisi at present; that despite increasing levels of disaffection, they are not showing it. They feel a certain sense of shame that they approved the bloodshed at the time; that they were in some way complicit.

So what was once an iconic site, Tahrir Square in Cairo, has become a place best ignored. Whereas nine years ago, the square was the epicentre of the movement and set pulses racing among Egyptians and pro-revolutionary visitors, today it leads a Cinderella-like existence; best kept out of sight and therefore out of mind.

Construction workers are still there, eliminating what remains of past events. The paving stones are being removed and replaced by cement. After all, people may have the same ideas again and use them as projectiles against the security forces. Just as in late September in Egypt, when hundreds took to the streets against Sisi and 2,000 people were arrested.

Baghdad's Tahrir – a sacred place

In Baghdad, the magic of Tahrir Square has not yet been extinguished, although the demonstrators here also suspect that ultimately, they have no chance of achieving their goals. The burned-out tents have already been replaced, a solidarity rally attended by thousands of students encourages the campers to hold out. After all, here on the Tigris, it is not the movement itself that is being crushed under the weight of demoralising dispute as it did in Cairo, where everyone wanted to be leader and ensured he was acclaimed as such.

Three months after the start of protests in Baghdad, there is still no leader. And for good reason. "They'll either be bribed and their silence bought for huge sums," says Sarah, a medical student distributing food on the square. "Or they'll be killed immediately."

And even if there were leaders, they would not be named. No, the dispute that is grinding down the movement in Iraq is the conflict between the U.S. and Iran. Iran, a nation that is currently doing everything within its power not to lose influence in Iraq. And for its part, the U.S. is doing everything it can to push back that very same influence.

Sarah comes every Friday bringing those still on Tahrir Square some of the things they need: blankets, rain jackets, umbrellas, food. This time, she's brought a small wood-fired oven from home.

The Baghdad nights are cold right now. The thermometer reading is just four degrees. "Tahrir is a sacred place," she says, but she's not talking about the Iraqi Christians' tent affixed with a photo montage of the square protected by the hand of Mary. She's thinking much more of recent events, that the square has remained largely untouched after days of raging battles all around it. An oasis for mostly young Iraqis dreaming of a better future.

Birgit Svensson

© Qantara.de 2020

Translated from the German by Nina Coon