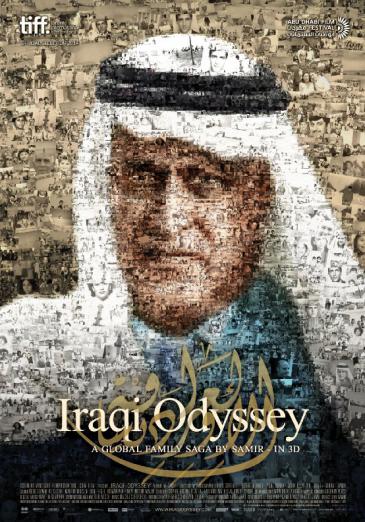

An Iraqi odyssey

Why do you call yourself Samir? Do you not have a surname?

Samir: My name is Samir Jamal al Din. My family name, Jamal al Din, was invented by my grandfather because he moved to the Iraqi city of Najaf to study Islamic law. That's why we're called Jamal al Din, which in Arabic means "the beauty of religion". In pre-Islamic times, "Samir" was the word for a man who would tell the tribe stories around the fire in the desert at night. I didn't want to say "Hello, my name is 'beauty of religion'" on a daily basis. I prefer to say: "my name is Samir" because I know how to tell stories. In my first two films, Jamal al Din appeared in the credits, but the film critics misspelled it. That's why I've been going by the name Samir since the 1980s.

How difficult is it to shoot a film with your own relatives?

Samir: This was one of the biggest obstacles for me because everyone in the family was afraid that I might reveal things that they didn't want to reveal or that if I left something out, it might be even worse because the omission would reveal even more.

I had to win my family's trust because those of them in the West know very well that authors here like to focus on the psychological analyses of their characters, i.e. that a whole media industry in the West makes a living from undressing people down to their underwear, so to speak. This is what they feared. Then they all sent me their letters and photos, a huge amount of material. Only then could I start my historical research.

Why do you start with the story of your grandfather?

Samir: My grandfather was born on the other side of the border river Shatt al Arab on former Iranian territory, which was the Emirate of Mohammerah at the time. That's where I begin our family story. My grandfather only became a liberal thinker through the study of Islamic law in Najaf. He came to the conclusion that we need freedom and democracy and that his children had to be educated to be curious about the world and should not be indoctrinated.

Is this the reason why your father, uncle and aunts – who were officially Shias – all opted for mixed marriages?

Samir: My grandfather, who belonged to the new middle class, gave all his children the freedom to marry whomever they wanted. My aunt married a Kurd, my cousin married a Christian, another aunt a Sunni, my father a Christian. But in those days, nobody cared about religious background. No one asked anyone else what their religion was. This intellectual middle class, which refused to be dictated to by religion, already made up one million people out of a total population of five to six million Iraqis in the 1950s.

In today's Iraq, on the other hand, things are very different indeed. You had to change cars when driving from one Baghdad district to another. Why is that?

Samir: I was doing some research in the city of Najaf at the end of 2013. Then we drove to Baghdad where I had arranged to meet with my half sister and my cousins. Although they all come from a Shia background, they all lived in the Sunni middle class district. Previously, almost all of Baghdad was religiously mixed; today there are only two small districts.

My driver, who was from Najaf, was incredibly nervous. Panicking, he said: "We are crossing into a Sunni area, and the checkpoints are manned by people who have something against us Shias." So we had to stop and change the number plates. Nothing happened, but this fear in people's minds is very strong.

Why is it that Iraq, which was a modern and socially just society in the 1950s and 1960s, has fallen apart?

Samir: Although my film is not a sociological analysis, there are many reasons for this collapse. The interference of the superpowers, which were partly responsible, began as early as 1914. Britain went to war against the Ottoman Empire in order to secure the oil fields. It fought for four years until it brought Iraq under its control; and all that just because the English fleet switched from coal to gas in 1914. Oil is truly Iraq's curse.

Iraq's decline in the 1950s, however, was homemade and was the result of Iraqi politics. The country found itself on the front line of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the USA. This influenced the life of every single political activist, including my family. They were involved in the Communist party, which was in fact a bizarre contradiction: a middle class family that was committed to the rights of workers and peasants. They didn't want to be part of the West, but they nevertheless fought for modernity.

Where did you find the historical footage for your film?

Samir: That was a real problem. We went to the Iraqi National Archive. The director drank tea with us for hours and finally said: "The best thing for you to do is to look for it all on YouTube!"

I actually found the footage of the Baath Party congress – where you really see what kind of a fascist and Nazi-inspired organisation it was – on YouTube. At this congress in 1979, Saddam Hussein seized absolute power and wanted to eliminate all party members who could have posed a threat to him, beginning with the lowest ranks.

This footage shows Saddam Hussein sitting on stage, smoking a cigar…

Samir: ... at one point, he even takes out a handkerchief, as if the whole episode filled him with sadness. The people in the hall are called on one after the other and led away. Outside they will be shot dead. Legend has it that Saddam himself shot them after the party congress. I intersperse these terrible historical events with amusing stories about my family.

Given the difficult filming conditions in Iraq, did this irony help you?

Samir: My grandfather's roots helped me in Najaf. After he had completed his studies, he wanted to return to his father on the Iranian side of the border river. Family legend has it that during the crossing, the ferryman got angry because he had to ferry so many young man wearing turbans across the river. He complained that he was not allowed to ask them for money for the journey. My grandfather – and this is an illustration of his sense of justice – was so moved that half way through the crossing, he threw his turban into the water and told the ferryman: "Look, I'm not an Islamic scholar anymore, so you have to take my money for the crossing!" After this incident, he never wore a turban again and renounced all his religious privileges.

Your uncle Sabah fled the military coup of 1958 to Moscow. Later he succeeded in escaping to the West on a faked passport…

Samir: My uncle was the survivor in our family. He actually managed to get from Moscow to West Germany on a forged passport. He later worked as an eye doctor at the American Hospital in Frankfurt, until the FBI became suspicious that he might be a Communist, and he was dismissed.

Why did your father, who was married to a Swiss woman, return to Iraq?

Samir: My father tried to fit in perfectly and to integrate into the country of his wife, but he didn't succeed. That's why he decided to return to Iraq at the end of the 1970s. He paid for this mistake with his life: he died in the Iran–Iraq war. I was, of course, astonished when I found out that he intended to go back to a dictatorship, but then he said to me: "I've lived in Switzerland for many years, but to this day, I don't have a single Swiss friend – only Italians, Germans, Spaniards and Indians.

Interview conducted by Igal Avidan

© Qantara.de 2015

Samir was born in Baghdad in 1955. In the 1960s, he moved to Switzerland with his family, where he completed his studies at the Academy of Arts in Zurich and later trained as a typesetter. Since the early 1980s, he has been working as a cameraman, author and film director. In 1994, he, filmmaker Werner Schweizer and producer Karin Koch established the Dschoint Ventschr film production company, which focuses on promoting young Swiss talent. He has made over 40 short and feature-length films.