For a Plurality of Koranic Interpretations

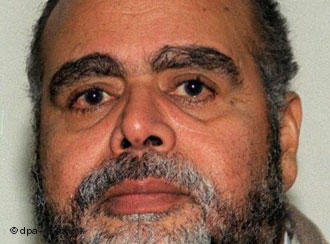

In the course of your work how do you relate to those aspects of the historical Islamic tradition which you think might be opposed to the notion of women's and children's rights?

Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd: Every tradition has both negative as well as positive aspects. The positive aspects are to be further developed, while the negative aspects need to be discussed closely, to see if they are indeed essential elements of the faith or are actually simply human creations.

How does this work relate to what you have been previously engaged in?

Abu Zayd: I see it as part of my long interest in Islamic hermeneutics, the methodology of understanding the Koran, the Sunnah and other components of the Islamic tradition. Of particular concern for me are certain assumptions in popular Islamic discourse that have not been fully examined, and have generally been ignored or avoided. Thus, for instance, Muslim scholars have not seriously reflected on the question of what is actually meant when we say that the Koran is the revealed 'Word of God'. What exactly does the term 'Word of God' mean? What does revelation mean?

We have the definitions of the Word and revelation given by the traditional 'ulama, but other definitions are also possible. When we speak of the 'Word of God', are we speaking of a divine or a human code of communication? Is language a neutral channel of communication?

Was the responsibility of the Prophet simply that of delivering the message, or did he have a role to play in the forming of that message? What relation does the Koran have with the particular social context in which it was revealed? We need to ask what it means for the faith Muslims have in the Koran if one brings in the issue of the human dimension involved in revelation.

Are you suggesting that the Koran cannot be understood without taking into account the particular social context of seventh century Arabia? In other words, are there aspects of the Koran that were limited in their relevance and application only to the Prophet's time, and are no longer applicable or relevant today?

Abu Zayd: What I am suggesting is that in our reading of the Koran we cannot undermine the role of the Prophet and the historical and cultural premises of the times and the context of the Koranic revelation. When we say that through the Koran God spoke in history we cannot neglect the historical dimension, the historical context of seventh century Arabia. Otherwise you cannot answer the question of why God first 'spoke' Hebrew through his revelations to the prophets of Israel, then Aramaic, through Jesus, and then Arabic, in the form of the Koran.

In a historical understanding of the Koran one would also have to look at the verses in the text that refer specifically to the Prophet and the society in which he lived. Some people might feel that looking at the Koran in this way is a crime against Islam, but I feel that this sort of reaction is a sign of a weak and vulnerable faith. And this is why a number of writers who have departed from tradition and have pressed for a way of relating to the Koran that takes the historical context of the revelation seriously have been persecuted in many countries.

I think there is a pressing need to bring the historical dimension of the revelation into discussion, for this is indispensable for countering authoritarianism, both religious and political, and for promoting human rights.

Could you give an example of how a historically grounded reading of the Koran could help promote human rights?

Abu Zayd: Take, for instance, the question of chopping off the hands of thieves, which traditionalists would insist be imposed as an 'Islamic' punishment today. A historically nuanced understanding of the Islamic tradition would see this form of punishment as a borrowing from pre-Islamic Arabian society, and as rooted in a particular social and historical context. Hence, doing away with this form of punishment today would not, one could argue, be tantamount to doing away with Islam itself. By thus contextualising the Koran, one could arrive at its essential core, which could be seen as being normative for all times, shifting it from what could be regarded as having been relevant to a historical period and context that no longer exists.

If one were to take history seriously, how would a contextual, historically grounded understanding of the Koran reflect on Islamic theology as it has come to be developed?

Abu Zayd: As I see it, Sunni Muslim theology has remained largely frozen in its ninth century mould, as developed by the conservative 'Asharites. We need to revisit fundamental theological concepts today, which the Sunni 'ulama, by and large, have ignored, for there can be no reform possible in Muslim societies without reform in theology. Till now, however, most reform movements in the Sunni world have operated from within the broad framework of traditional theology, which is why they have not been able to go very far.

How would this new understanding of theology that you propose reflect on the issue of inter-faith relations?

Abu Zayd: When I suggest that we need to reconsider what exactly is meant by saying that the Koran is the 'Word of God', I mean Muslims must also remember that the Koran itself insists that the 'Word of God' cannot be limited to the Koran alone. A verse in the Koran says that if all the trees in the world were pens and all the water in the seas were ink, still they could not, put together, adequately exhausted the Word of God.

The Koran, therefore, represents only one manifestation of the absolute Word of God.Other Scriptures represent other manifestations as well. Then again, many Sufis saw the whole universe as a manifestation of the 'Word of God'. But, today, few Muslim scholars are taking the need for inter-faith dialogue with the seriousness that it deserves. Most Muslim writers are yet to free themselves from a rigid, imprisoning chauvinism.

How does this way of reading the Koran deal with the multiple ways in which the text can be understood and interpreted?

Abu Zayd: The Koran, like any other text, can be read in different ways, and there has always been a plurality of interpretations. The text does not stand alone. Rather, it has to be interpreted, in order to arrive at its meaning, and interpretation is a human exercise and no interpreter is infallible. As Imam 'Ali says, the Koran does not speak by itself, but, rather, through human beings.

True, Muslims from all over the world do share certain rituals and beliefs in common, but their understanding of what Islam and the Koran are all about differ considerably. It is for us to help develop new ways of understanding Islam that can promote human rights, while at the same time being firmly rooted in the faith tradition.

Yoginder Sikand

© Qantara.de 2011

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de