Life in a war zone

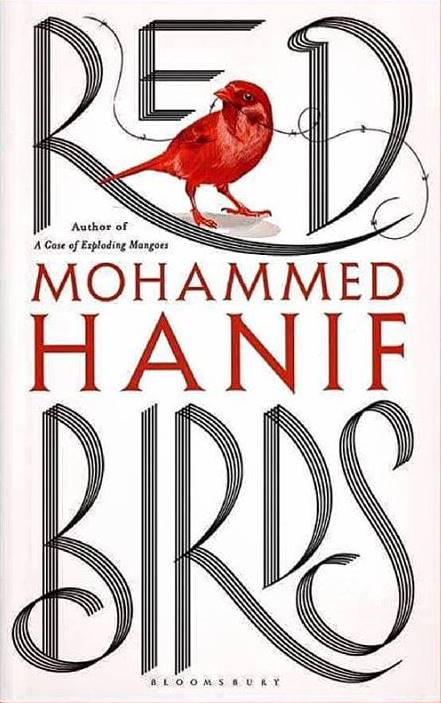

On the surface "Red Birds" seems to be a novel about the brutality of war and the United Statesʹ disastrous foreign policy. But this is only half the story…

Mohammed Hanif: Indeed – I was more obsessed with the idea of home. Because the home itself is a battleground – as we all know – and it's universal: here, there and everywhere. I therefore wanted to describe the inner dynamics of a family that has been forgotten by the world – and in which one of the two sons disappears without a trace. This happens a lot, not just in India and Pakistan, but also in war-torn regions around the world. But what does a family do when something like this happens? In addition, we, the educated and peace-loving middle class, have learned to pretend that we have nothing to do with all the terrible wars and conflicts out there. I wanted to take the readers by the hand to lead them out of the comfort of their living rooms and into another space.

Again you play with the stylistic device of satire. This time you take it to extremes – although "Red Birds" is perhaps your darkest novel so far. Is satire the best remedy against the atrocities of life?

Hanif: Would that it were. It took me seven years to write this novel – and I lost some of my closest friends during that period. And since we are always in contact with people who are close to us because of the technologies we use, you are in the middle of a conversation, you make plans, you have a dispute and tell each other stories: what happened in the office in the morning, what you dreamt. In short: you also want to entertain the others. But suddenly – and I wanted to take this into account – all this was interrupted by death. Yet somehow I wanted to continue that conversation – even though those people are no longer there.

There are three narrator’s voices. One is an American major rescued in the camp he should bomb. And one is a dog: how did that come about?

Hanif: I was struggling. First there was a dog in the novel but he was not allowed to speak – as dogs shouldn’t be allowed to speak. And in my personal life dogs have broken my heart many times. So I would be sitting there all by myself, and my dog would be kind of staring at me. And to me it seemed that he was saying: what about me? So one day I gave up and I said: okay, come on, join the party. And after that it made sense to me. He started to connect lots of things, which I hadn't been able to connect before.

The third narrative character is Momo, a child who grew up with war. Normally you would see such a child as a victim. But he isn't. He knows very well how to capitalise on the situation. Do we have to re-think our notions about living under such conditions?

Hanif: I have indeed met many children who have experienced terrible things and survived. They have a kind of energy that we don’t imagine they should. We think they should all be in need of being protected and cared for. But Momo sees himself as a man of the world. He is ambitious. He has plans. And he has lost his brother so he has to shoulder the responsibility of the household. So he may be a tragic figure – but he is certainly not a victim. Nor does he see himself as one.

Momo is on a quest to find his missing brother. Just as in Pakistan, where recently more and more people seem to be disappearing. Your two previous novels were decidedly set in Pakistan, this one is not. Was that too risky in view of the subject matter?

Hanif: No, but I had already written a work of non-fiction about it: a little pamphlet, with stories of the families of people who are missing: what happens to them is absolutely horrifying. You can't continue to lead a normal life. Nor can you give up hope. And this is not just in Pakistan or in India. In Kashmir, there are women who are called half-widows because their husbands have been gone for years. Spending time with these families certainly influenced my thinking. But I wanted to avoid too much local colour and specifics. A home is a home – it may be a hovel made of mud, it may be a mansion. A family is a family – and a mother is a mother.

The more we progress through the novel the more the mother in it becomes important. Indeed it is she who concludes the novel.

Hanif: Spending my time with the relatives of missing persons, I increasingly noticed that most of them were women: mothers, sisters, some of them 8- or 9-year-old girls. So for me it was quite a natural progression that as the story moves forward we see more of her, we notice her grief and her confusion. It was also deliberate that she was not given a voice in the first half of the novel. That's what happens in real life: in the first instance women should keep quiet. But when they do speak, you will find their voice is a very strong. They are the ones who keep everything together.

The novel also has the feeling of being swathed in a transcendent veil.

Hanif: I was interested in the idea of where people go when they die or disappear. Because we still have our memories of them. We still have their voices in our head. We know what it felt like to touch them. We sense their smell. Or think of something that they said or did. And we smile. Are they still around somewhere? Is it my duty to remember them? Are they watching me? Do they miss me too? Or is it just a one-sided thing? I'm not a spiritual person and I had never thought about all this before. But that changed the year I lost many close friends, as I said. Suddenly I was interested in the idea of the afterlife.

In the end the reader doesn’t know: is the son rescued or not? Is the mother dreaming or not?

Hanif: Many terrible things happen to people, especially women. One of them is that one must not give up hope. We think that having hope is good per se. But what if you are simply not allowed to feel hopeless?

Interview conducted by Claudia Kramatschek

© Qantara.de 2019