The trap of the century

"Time passes and passes. It passes backwards and it passes forward and it carries you along, and no one in the whole wide world knows more about time than this: it is carrying you through an element you do not understand into an element you will not remember. Yet something remembers – it can even be said that something avenges: the trap of our century, and the subject now before us."

You cite the American writer James Baldwin in the epigraph to your novel. How does "the trap of the century" relate to your novel?

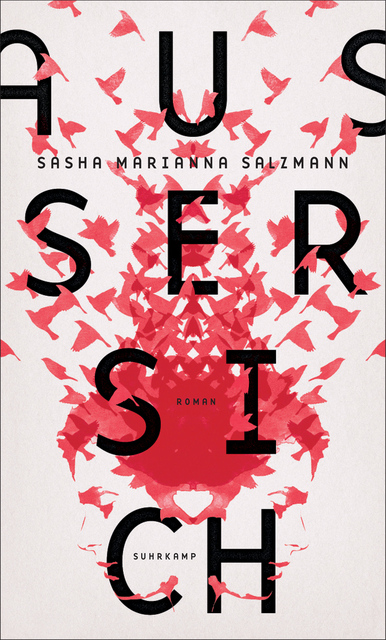

Sasha-Marianna Salzmann: We have sinned and we will have to pay for it. The past is never over: it lives on in all of us. This is the idea at the centre of my novel "Ausser Sich" (Beside Yourself). I believe we carry more than just our family histories within us – historical events also leave their mark on us. And both, of course, are inseparably linked.

Certain events recur in the novel. Does this way of telling the story reinforce the idea of the past living on within us?

Salzmann: These recurring events reverberate through the novel. Many things determine our actions; things that we cannot comprehend. Our bodies store information that we simply cannot understand intellectually. My characters suffer because of events that they were not even present at, that they cannot remember happening, or that they cannot be sure happened in the way they remember them. My protagonist Ali runs off saying, "I have no gender, I have no language, I have no family." But something is causing her/him terrible pain. Ali is forced to face up to this unknown person within her/him-self. Otherwise there will be no future for her/him.

Another past event in the novel that has this reverberatory quality is the Shoah. But you made a deliberate choice not to have this as the main focus in the novel.

Salzmann: It is a trap that most things Jewish are usually linked to the Shoah. It is impossible to imagine Jewish identity today without the Shoah.

For some years now, my colleague Max Czollek and I have been working on developing a disintegration concept that attempts to break with stereotypical notions of ʹthe Jewʹ as someone bounced back and forth like a ping-pong ball between anti-Semitism, Israel and the Shoah.

These three things have only a limited relevance for Jewish identity in the 21st century. The themes in my novel are very different.

Ali has leftist sympathies and speaks about "Palestine" – but about a time before 1948. The mother later refers to it as "Israel" – did you mean to hint at that debate?

Salzmann: This is quite similar to the treatment given to the Shoah. Jews are continually confronted with such things, but what do we do if that is not what our work is about? What if this country isnʹt so important to us and we simply donʹt identify with it?

As a political person, I can relate to Israel/Palestine in the same way as I would to any other country where I know people who are close to me. The country is no longer an abstraction, it has human faces. As a novelist I try to be meticulous with my language – the words I give to my characters are carefully chosen.

The events in the novel are not things that you yourself experienced, yet there are aspects of the book that are clearly autobiographical ... what was it that appealed to you about mixing the biographical with the fictional?

Salzmann: I am interested in autobiographical fiction as a form. So, I took some parts of my own story and the story of my family, and the rest I invented. I worked my way through family myths and old photographs of people no-one in my family could identify.

Since memory is the subject of my novel, I found this connection important. My career in theatre has also taught me that everything is attributable to my body and my biography anyway, so I described Aliʹs appearance like my own. In order to play with it.

You frequently make use of metaphors and comparisons. There is a particularly beautiful comparison of a minaret with many hanging microphones to a "rose branch with thorns". Was it your stay in Istanbul in particular that inspired you to think and write in metaphors?

Salzmann: For me, Istanbul itself functions like a metaphor, because the city seems to exist in so many centuries at the same time. I am very much in love with Istanbul; my first impulse was to write a declaration of love. It seemed to me that everything was possible there and at the same time, so difficult. The city is like some great amorphous creature and I was transformed by it. I donʹt want to romanticise the city and its political situation, because I know how serious things are. But maybe there is no other way to look at something you love. A century of history unfolds in the story of a family across four generations. Where did the idea of describing the experience of gender fluidity as part of this story come from?

Salzmann: The contemporary philosopher Paul B. Preciado, says of his experience with testosterone: "The transformation of an entire century flows through my veins". I felt inspired by that. Migration between genders and countries is interlinked. With "Ausser Sich" I wanted to question things and try to understand. I am not cisgender myself and when I was in Istanbul, I lived in a community that consisted mainly of transgender women. My view of Istanbul came from the perspective of that community and I felt the need to include those women in my portrayal.

Iʹve thought a lot about why it is that people are so irritated by there being more than two genders. I accept that for some people the concept of binary gender identity is an engrained part of the way they view the world. Still, I think this is something we need to negotiate. When Simone de Beauvoir said, "one is not born, but rather becomes, woman", it revolutionised our thinking. Now we have arrived at the thought that it is not only the female, but gender itself that is a construct.

In my novel I was trying to explore this sense of flux on all levels – in language, gender and in nations. The familiar binary systems we grew up with are coming apart. There is much more communication now between so-called minorities, fostered by new technologies. But it brings out peopleʹs fear of the unknown and that leads to them to vote for fascists.

Some people have read my book as a response to this shift to the right in Europe, because the book is full of the kind of things the Right loves to rant against. But I have not written anything against the Right. Iʹve not written against anything or anyone. I wrote for us, that is for all those who have not fallen in behind the Right, and for all those in whom I believe and who have a right to existence and acceptance.

Migration does not kill, but exile may… In the novel, the mother Valja says migration kills. That she should say this is understandable, but is it also something you would agree with?

Salzmann: I am of a different opinion, but it is true that it can kill. For me, emigration is the attempt to survive. I believe that people must change and develop to survive and such movement is part of that development. I believe that exile kills because it is forced and that you need a lot of luck and help so that the process does not kill you internally. When it is a voluntary act, migration can be something wonderful – but you know, that is something quite rare.

Interview conducted by Noha Abdelrassoul

© Qantara.de 2019

Translated from the German by Ronald Walker