Radicalisation in the suburbs

Mr Khosrokhavar, two weeks ago there was an Islamist-motivated knife attack in Paris. What kind of radicalisation did the attacker undergo?

Farhad Khosrokhavar: What weʹre seeing now are attacks by individuals, in which barely any other people are directly involved. If you like, these knife or vehicle attacks are a kind of revenge for the Westʹs fight against IS in Syria. These attacks are much more limited than the type of attacks we saw in Paris on 13 November 2015, which killed 130.

Is this attacker another migrant from a disadvantaged banlieue, a deprived French suburb?

Khosrokhavar: We know too little about the attackerʹs background so far, but he was of Chechen origin, becoming a naturalised French citizen in 2010. He is a young person with a background of migration and he lived in Strasbourg-Elsau, a social flashpoint. Such attackers are often young men like him, from migrant families in disadvantaged suburban areas. They feel rejected and stigmatised, have usually left school without qualifications and see no prospects for the future. Many of them are unemployed or in precarious jobs. These suburban areas have become hot spots of radicalisation. They exist in cities throughout Europe, not just in France.

As well as radicalised young men from disadvantaged sectors, there have also been attacks by middle-class perpetrators. Are these isolated cases?

Khosrokhavar: Theyʹre not isolated but they are a minority of cases. A quarter to a maximum of a third of the attackers are middle-class, although we donʹt have precise statistics. In the majority of incidents, the attackers are young people from disadvantaged sections of society, whose families immigrated to France and whose lives play out in the desolate suburbs.

Do the two groups have anything in common?

Khosrokhavar: Not in social terms; what connects them is their identification with radical Islam. In the cases where disadvantage plays a role, itʹs primarily hate for society, the feeling of being rejected, a second-class citizen, that ends up driving them to jihad. There are negative terms for these migrants almost everywhere in Europe. In France, theyʹre called "Francais sur les papiers" (French on paper), in Germany "passport Germans", in the UK "Pakis". This dimension is very important for understanding radicalisation.

And the middle-class attackers?

Khosrokhavar: In their case, hate for society isnʹt a significant factor to begin with. It has more to do with uncertainty about life. Whatʹs striking about these young people is their lack of any humane utopia. That gap represents a huge window of opportunity for jihadist utopia. The middle-class attackers donʹt have criminal records and they donʹt live in social flashpoints. They donʹt feel marginalised, so they have very different psychological prerequisites.

Do you have an explanation for the frequency of attacks in France?

Khosrokhavar: Firstly, France boasts Europeʹs largest Islamic community, with about five million Muslims. By contrast, only about three million Muslims live in both Germany and the UK. The French Muslim community also has a different structure. Whereas Germany is mainly home to Muslims of Turkish origin, French Muslims usually originate from northern Africa. Franceʹs colonial history plays a role here, as does its particularly strict version of laicism. The ban on headscarves in the public administration and schools system, or the ban on Muslim sports clothing in the name of laicite, leads to more tension, whereas in Germany or the UK people arenʹt necessarily fond of headscarves, for instance, but theyʹre more tolerated than in France.What role does colonial history play?

Khosrokhavar: Unlike the relationship between France and North Africa, Germanyʹs history with Turkey does not include colonialism. The Turkish Muslims have strong ties within the community, working for the family and the community is highly valued, which is not the case among Algerians or Moroccans in France. Historically Algerians and Moroccans have been exposed to very different pressures. In the case of Algeria, there was the civil war between the military and radical Islamists from 1991 until 2002/03, which cost 200,000 lives. Among Moroccans, itʹs primarily the Berbers who stand out. They experience rejection and poor treatment from all directions. A large proportion of Moroccan jihadists are Berbers. They struggle with major identity issues, being seen as neither French nor Arab. Such pressures lead to more attacks happening in France than in other countries.

Youʹve spoken of the attackers as "born-again Muslims" who originally come from de-Islamised families and then rediscover religion in a radical form. What role does Islam play in that radicalisation?

Khosrokhavar: That varies from country to country. In France it is indeed the younger generation that has lost its ties to Islam and is now seeking a new identity in jihadism. These youngsters want to reverse the role imposed on them. That means they transform their inferiority into superiority by becoming jihadists. In many cases, these attackers started out as petty criminals sentenced to prison. Behind bars, they turn the equation around and sentence society to death. As jihadists, they become international celebrities. Their photos are broadcast around the world at peak time. So itʹs this re-evaluation that describes their path to radical Islam.

Does the same apply in other European countries?

Khosrokhavar: In the UK thereʹs a closer link between traditionalist Islam and radicalisation. In France, strict laicism has to a certain extent meant cutting the cultural continuity of Islam, which is not really the case in Britain. The Turkish community in Germany is strongly influenced by the Turkish religious affairs authority Diyanet. This institution makes sure that imams donʹt become too radical, meaning Germany experiences a controlled form of Islam with little scope for radicalisation.

When someone attacks passers-by with a knife, it usually prompts a local news item about a criminal offence. As soon as they do so in the name of Islam, the story goes international. What makes this kind of murder so horrifying?

Khosrokhavar: Itʹs because Islam is seen as something absolutely alien in Europeʹs largely secular societies. If someone kills in the name of Corsican or Northern Irish nationalism, people reject it of course, but they understand the historical context. For Europeans, jihad comes from a completely different world. At the same time, it has symbolic meaning, which is central. Anyone killing in the name of jihad is revoking peaceful co-existence at a fundamental level.Is a form of violence returning that Europe once considered overcome?

Khosrokhavar: Thatʹs exactly it – in the European secular model, violence on religious grounds was considered a thing of the past. Jihad is all about religion, about God. These are very different categories, incomprehensible to Europeans. Thatʹs why the impact of jihadism on society is so different compared to that of left-wing or right-wing terror, for instance.

Aside from that, in jihadism indiscriminate violence erupts in a very different brutality than the violent left-wing extremism of the Red Army Faction in Germany or the Italian Red Brigades. These groups were also violent, but they focused on certain groups of people such as capitalists, the military or politicians, not just anybody. Jihadists murder randomly, however. That dimension is very frightening.

Do you share the assessment that Islamist terror is the main threat to Europe?

Khosrokhavar: In my view, the threat is more of a symbolic one than a real danger, even though it has killed 200 people in France over the past two years. Under symbolic aspects, it is a serious threat because Islamist terrorism is driving Europe into the hands of right-wing populists. Thatʹs the great danger, be it PEGIDA and the AfD in Germany, the Front National in France or the Dutch right-wing populists. In the context of Europe as a whole, the numbers of victims arenʹt huge but theyʹre always innocent people, which we have to condemn outright. Itʹs especially the questioning of European civilisation with its secular democracy in combination with indiscriminate violence that whips up so much fear.

How can Europe react adequately?

Khosrokhavar: Thereʹs a short-term option and a long-term one. In the short term, the security apparatus and the police have to react, but in the long time we have to take a look at the social dimension as well. Urban structures can create jihadism. We have more and more deprived areas in our cities, where migrants have no perspectives at all. We have to try to offer these young people the same opportunities to participate in society. Sociological studies show that a young man named Mohammed does not have the same opportunities in Germany, France or the UK as someone called Robert.

Another factor is that about a quarter to a third of Muslims hold fundamentalist views. That doesnʹt mean theyʹre jihadists. But it does show how much work we have cut out for us. We have to explain more strongly what it means to be a citizen, what democracy means – and at the same time create genuine equal opportunities. We can only solve the problem of terrorism in the long term if we tackle these issues. Itʹs an illusion to believe we could fight terrorism by means of security policy alone.

Youʹve written that the decline of political institutions is alarming in this context. Why is that?

Khosrokhavar: Political institutions lend meaning to our living together. There have been many different utopias for co-existence in Europe – socialist or republican utopias in France, feminist and nation-state utopias – but all of them have been lost. Thatʹs what makes the repressive utopia of "Islamic State" (IS) attractive for some young people. Societies need utopias, but they have to be governable. Be it a utopia of human rights, feminism, ecology or social justice: people need these visions of the future.

Interview by Claudia Mende

© Qantara.de 2018

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire

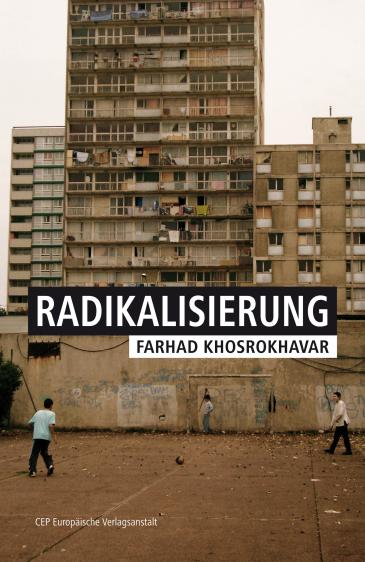

The French-Iranian sociologist Farhard Khosrokhavar is director of studies at the Ecole des hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris. His book "Radicalisation" was published in German translation by the Europaische Verlagsanstalt in 2016.