Trouncing triple talaq

The message is clear: The Indian government is calling on the Supreme Court to declare the practice of "divorce by repudiation" – known as talaq – and polygamy unconstitutional.

This landmark decision on a central issue relating to the family law of the Muslim minority brings a dispute that has been simmering for decades, indeed since the founding of the Republic, to a crucial turning point. The question of which divorce law should apply to India's Muslims has always been more than a legal dispute. It concerns the precarious relationship between the religious majority (Hindus) and the religious minority (Muslims) and is therefore a fundamental question of state policy: how secular is the Indian Republic?

Secularism is written into India′s Basic Law as a constitutional principle. But in the world's largest democracy, constitutional aspirations and the reality on the ground often diverge. The same applies to the situation of the 180 million followers of the Muslim faith in India.

Only Indonesia has a larger Muslim population than India. There, when it comes to civil law, Muslims are bound by a separate – Islamic – personal law. For India's Muslims, however, be the case in hand marriage, divorce, adoption or inheritance, Sharia is the measure of all things.

Debates over whether this special status is compatible with the uniform character of India and frequently celebrated secularism of the south Asian multi-ethnic state, are as old as the Republic itself.

Islamic law is a religious freedom

Expressed in simple terms, there are two opposing camps: advocates of an Islamic personal law cite the principle of religious freedom, which occupies a high status in India's constitution. For them, retaining an Islamic legal code is a way of fostering and preserving Muslim identity.

On the other side are the champions of a uniform civil law; they stand for the principle of secularism and demand that one and the same law should apply to all Indian citizens – irrespective of their religious affiliation.

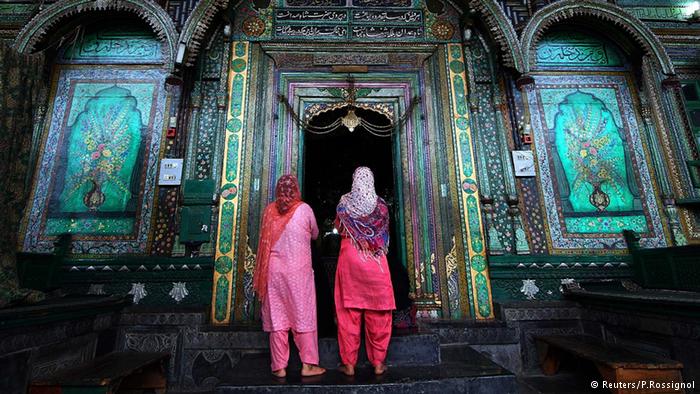

In Indian public discourse, which is largely influenced by the major English-language dailies, supporters of Sharia are given a tough time. Many column inches are devoted to reports on Muslim women complaining about the impact of the divorce practice known as the "triple talaq".

TheTimes of India reports the case of Ishrat Jahan, who became the victim of the controversial "shotgun divorce", when her husband said the word "talaq" (literally: repudiation) three times over the phone from his home in Dubai. According to the Islamic legal code in force in India, this voided the marriage. Now, the repudiated wife is sueing for maintenance and child custody. The case has been taken to the highest court in the land and – with other, related cases – made the imminent Supreme Court decision necessary.

One law for all

For cosmopolitan, secular Indians, the "shotgun divorces" achieved by the triple acclamation of the husband are an intolerable remnant of an era thought to have been relegated to the past long ago: "this is a brand of IS law that prevails in India," the Associated Press news agency quotes the Supreme Court accredited lawyer Monika Arora as saying. "No progressive country can tolerate this.

A variety of non-governmental organisations are campaigning for the abolition of the special divorce law for Muslims. One campaign claims it has gathered 50,000 signatures and quotes a less representative poll, in which 92 percent of Indian Muslim women have come out in favour of abolishing the "shotgun divorce".

Champions of Sharia law in India have issued a calm response: "These fringe groups have no credibility among Muslim masses," says Asma Zehra. A wearer of the full veil, she is a spokesperson for the "All India Muslim Personal Law Board" (AIMPLB). This is the rather clunky name for the association formed in 1973 with the primary objective to safeguard an Islamic personal law for India's Muslims. Within the politically fragmented population, the AIMPLB is regarded as the leading and most influential organisation of the religious minority.

"All those who want change and unprincipled lifestyles are free to follow the civil code of the country," is the advice that Asma Zehra has for her opponents. While this might be an option for well-educated Muslims in the anonymity of urban centres, it is unlikely that the mass of predominantly uneducated, poor women are in a position to resist the social pressure of the establishment in what continues to be a largely patriarchal society.

Wide support for a ban on ″shotgun divorce″

In the current debate, the government is choosing a middle way and avoiding total confrontation with the largest Muslim association: what is absolutely clear is the desire to see a ban on "shotgun divorce" and polygamy. Meanwhile a demand for the introduction of a uniform civil law binding for all religious communities, as announced in the election programme of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, Indian People's Party) of Narendra Modi, has so far failed to materialise.

"Gender equality and dignity of women are non-negotiable overreaching constitutional values and can brook no compromise," reads a government paper. To give the argument greater clout in Muslim target groups first and foremost, the government refers to the legal practices in a series of majority Muslim nations, which are mentioned by name: Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Morocco, Tunisia, Turkey, Indonesia, Egypt and Iran.

"The fact that Muslim countries where Islam is the state religion have undergone extensive reform goes to show that the practices in question cannot be regarded as integral to the practice of Islam," the paper says.

It is an irony of history that of all parties, it is the Hindu nationalist BJP, politically on the far right of the spectrum, that is presenting itself as the champion of secularism and the rights of the Muslim woman. The political home of the socially marginalised Muslim minority, which bemoans manifold discrimination, is traditionally the Congress Party, currently sitting on the hard benches of the opposition.

Critics accuse the party of Gandhi and Nehru of making common cause for too long with the conservative Muslim establishment and the religious elites of the minority for tactical electoral reasons, thus missing the signs of the times in the process.

Ronald Meinardus

© Qantara.de 2016

Translated from the German by Nina Coon