Seeing war through the eyes of a child

Ms Abirached, you were ten years old when the Lebanese civil war ended. When did you decide to tell the story of your childhood in a comic?

Zeina Abirached: After the civil war, there was very little discussion of what had actually happened. Lebanese school textbooks still stubbornly refuse to mention these 15 years of our past. It was while I was a student that I decided to draw my personal history in the form of a comic. I interviewed relatives and neighbours and put their stories together into one.

How much did your memories differ from your parents’ recollections?

Abirached: The conversations were very slow and difficult to begin with. My parents said they hardly remembered anything. But at some point the dam burst. That must have been painful for them. I was just a child when the war was going on in Lebanon. I had very little understanding of what was happening to us at the time. Talking to my mother unleashed a flood of memories, and one story led to the next. What was difficult then was to go deeper and deeper into situations and to link them up.

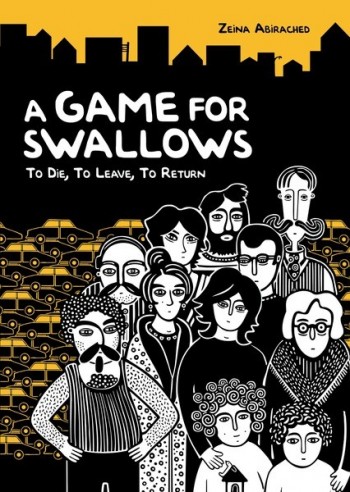

In your graphic novel A Game for Swallows, you take the readers back to one night in the midst of the civil war. You were living in East Beirut with your parents and your brother. The distance between you and the western half of the city was less than three kilometres. But in between was the demarcation line, the frontline of the war. How big did the world seem to you at the time?

Abirached: We lived on Youssef Semaani Street, with a high wall of sandbags intended to protect us from snipers. As a child, I thought that was where Beirut ended. After the war, I was able to cross the road for the first time and I found a wall on the other side with the graffitied slogan "A game for swallows". Some time later I realised that the swallows symbolised people caught up in the war – constantly up in the air and uncertain, always waiting for better days. Whenever I’m in Beirut I go back to that piece of graffiti. It’s a little piece of home for me. Sadly, I found out recently that the wall had been demolished. Beirut is in a constant state of flux. New buildings are put up and the old have to make way for them.

Your comic book "Je me souviens Beyrouth" ("I Remember Beirut") has just been published in German. Do you want to continue the series?

Abirached: Of course. In this volume, I tell stories from before and after 1990 – the end of the civil war. In 1989 my parents decided to flee to West Beirut, where it was safer for us. I couldn’t understand that I was still in the very same city. It seemed like I was now living in a foreign country, where the world seemed to be a safe place. I remember how surprised and stunned I was that the people on the other side of the city spoke Arabic too.

The style of your comic books is reminiscent of the Iranian artist Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novel "Persepolis" and the film of the same name, about her childhood and teenage years during the Islamic Revolution in Iran. Why did you also decide to use black and white as the dominant stylistic device?

Abirached: When I started drawing and was looking for a publisher I didn’t know Satrapi’s work. People who saw my illustrations came to me and said my style reminded them of "Persepolis". So I went to a bookstore and read her comic in ten minutes. I was bowled over. Lebanon and Iran don’t have a long tradition of comic books. We were inspired by European artists, particularly from France. Satrapi and I are building a bridge between the continents because, independently of one another, we combine this style with our stories.

Black and white are very important stylistic elements. They enable us to present reality in symbolic form. That makes pictures of violence more neutral. Don’t forget I’m telling my story from a child’s perspective. The things I don’t remember are symbolised in my book by entirely black pages.

In A Game for Swallows, you write that the people of Beirut had got used to living with the war. Lebanon is almost constantly rocked by bombings or armed conflicts. How much more can the Lebanese people take?

Abirached: People say that the Lebanese can adapt to almost any situation. We’ve developed special reflexes to deal with crises. I think, though, that when people talk about adapting it doesn’t mean we ignore reality and act as if nothing had happened. On the contrary: adapting also means fighting and resisting.

One illustration with the title "I remember July 2006" shows a canyon. You’re standing on one side and your family on the other, while bombs rain down from the sky. You were living in Paris during the Israel-Hezbollah war, and you could only follow events through the media.

Abirached: In retrospect, during the civil war I was in a relatively good position because my family and I were together. My parents never wanted to live anywhere but Beirut. We fled to Cyprus and Kuwait during the civil war, but we always came back. When the 2006 war broke out I had moved to France for my work, and I lived in constant fear of what might happen to them. Sometimes I was so caught up in thinking about them that whenever I was about to switch on a light I expected the electricity to have been cut off. There are a lot of problems with the electricity supply in Lebanon, particularly in wartime. I was in Paris then, and I still am now, but part of me is always in Beirut.

The interview was conducted by Juliane Metzker

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire

© Qantara.de 2014

Editor: Charlotte Collins/Qantara.de

Zeina Abirached: "I Remember Beirut" will be published in English by Graphic Universe in October 2014 (ISBN-13: 9781467738224).