Being queer and Arab

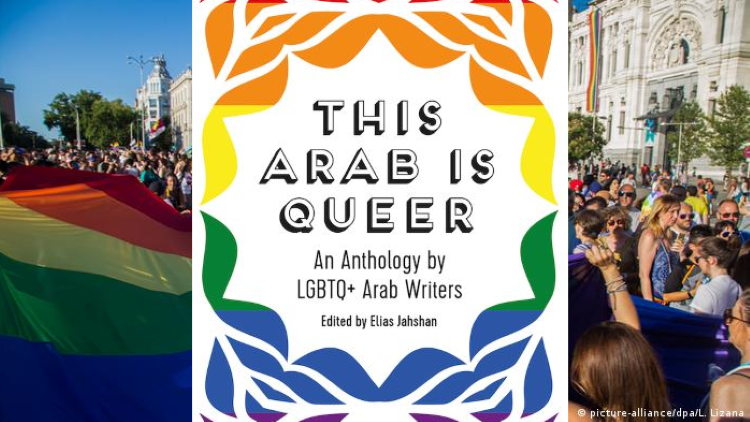

Created by a diverse and intriguing line-up of writers from all over the world, This Arab is Queer is certainly not intended to provide a comprehensive run-down of queerness in the Arab world. Moreover, while refusing to pander to people's stereotypical ideas about what it means to be gay in the Middle East world, the anthology also recounts the experiences of Arab people living in supposedly open European and American countries.

A note, these writers are very specifically Arab, and not necessarily – although the majority of them are – Muslim. This book doesn't include any essays from other Islamic countries, Southeast Asia, Africa, Iran, Indonesia, or Afghanistan. Each of those places and cultures will have their own stories to tell, so try to remember that when reading this book. It will help keep the stories in perspective.

These are highly personal stories and as such are reflective of an individual's experience. What we quickly discover is there's no such thing as the "Arab queer" – just as there's no such thing as the Canadian or German queer. Each person is a unique individual whose life has followed its own course.

Familiar stories of bigotry

While those raised in Middle Eastern countries may have experienced the same types of bigotry, and more of it than their European counterparts, the stories they tell sound all too familiar to ones you might have heard from the queer community in North America and Europe during the 1970s.

We have to remember, before we become full of righteous indignation, how only in the past decade has there been some acceptance of the queer community in the supposedly enlightened West. And judging by recent laws passed in the United States, that's still only tenuous at best.

In his introduction Jahshan also points out that many of the anti-homosexual laws in Arab countries actually only date back to colonial times. While he goes on to say that the laws in place are particularly draconian and the fault of the current rulers of each country, they in fact reflect the morality of their former colonial masters.

Jahshan adds that we only ever hear negative things about queer Arabs. The media seem to go out of their way to focus generalisations, rather than talking to actual people and listening to their stories.

“Telling us their truth”

This book is an attempt to give those people a platform. Its voices include all colours of the rainbow – from trans to bisexual: these are the voices that usually go unheard, especially if they are Arab. As Elias points out: this is the first-ever collection of its kind.

Eighteen writers have contributed their very personal essays to this book and each one shines a light into what is normally a very dark place. Not necessarily a bad place, but dark in the sense that these aren't areas we normally see into. While some of the stories do reflect the struggles people have living in countries where to be open about their sexual identity could mean death, the simple fact they have been should be regarded as positive.

Rather than hiding in shame and fear, these voices are telling us their truth. They're not asking for our pity or our understanding, they are just wanting to be heard. In fact, one of the things made clear by some of the writers is the last thing they want is to be rescued. Two of the essays; "Dating White People" by Tania Safi and "Trophy Hunters, White Saviours and Grindr" by Saeek Kayyani, are very explicit in their descriptions of the patronising attitudes they've encountered from non-Arabs.

From stereotypes about physical attributes and sexual preferences to the desire to save them from their horrible oppressive culture, the authors describe how they are made to feel diminished, even within the community they're supposed to be safe in. The fact that the majority of the essay writers love their culture and want to hold onto it makes the whole idea of them needing to be rescued from it even more insulting.

While many of the essays, for good reason, recount the difficulties the writer has had with family when it comes to their sexual identity, some of them do recount having supportive siblings. In some ways it seems most of the difficulties with families stem from not being able to talk about sexuality. Even if everyone in the immediate family knows a child is queer, the subject is studiously avoided. This also ensures nobody will be having "that" conversation with grandparents and other relatives.

A snapshot of someone’s life

What makes this collection so fascinating is not only the diversity of the stories, but how they all come straight from the writer's heart. It is as if each of the writers had only been waiting for this opportunity to speak, and now, given the chance, decades of pent-up emotions are spilling out onto the page.

Whether it is the words of Sudanese writer Amma Ali ("Intersectionality Was My Biggest Bully") talking about growing up African and queer in racist and homophobic Saudi Arabia, or author Danny Ramadan ("The Artist's Portrait of a Marginalized Man") writing about how he is constrained by people's expectations about what a queer Arab man should write about, or any of the myriad stories recounted within its pages, This Arab is Queer is a snapshot of someone's life.

The Arab is Queer is sometimes difficult, always intriguing and definitely compelling. Each essay is another little piece in a mosaic that when pieced together will give the readers a picture of the writers’ lives. It may only be a brief glimpse, but it is more than we've had before and that makes this book special.

© Qantara.de 2022