Confronting a dark chapter

Where did you get the idea for this novel? What inspired you?

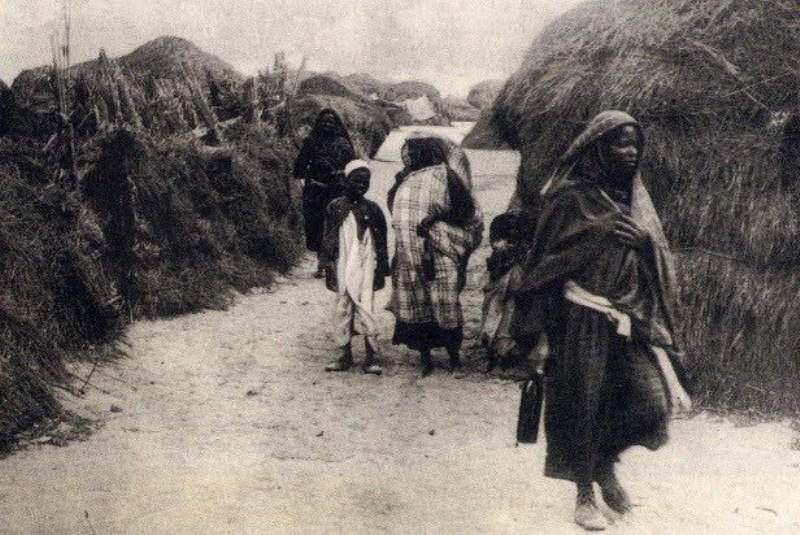

Najwa Binshatwan: I wrote ″The Slave Pens″ on both sides of the Mediterranean, in Libya and Italy. Back in 2006, I went to visit a historian friend in Benghazi to borrow some books. There was a book open on his table and a picture in it that caught my eye. I asked him where the picture had been taken. He replied that it showed the Zarayeb al-′Abeed – the slaves′ enclosure in Benghazi – now long gone. Apparently it was located by the sea on the outskirts of Benghazi, in an area now called al-Sabri wa al-Zurairi′iyya. Zareeba (pl. zarayeb) means corral, a place where you keep animals. The place aroused my curiosity. I wanted to find out if there was anything left of this history, whether any old people survived who had lived there and could tell me about it. My friend assured me that no one would agree to speak honestly and openly about their painful past. As it turns out, he was right: I didn′t manage to meet any one who was born or had spent their childhood there. The pens were gone and there was no sign of them, except for a few pictures taken once by the Italians prior to their invasion of Libya and once afterwards when a full survey was made of the site by the occupying forces. I asked for a copy of the picture.

I remember saving it on my PC, making it my background image. It kept drawing my attention. The subject of the picture was simple, but there was something that pulled me in and invaded my soul.

Two women, a boy and a child who could have been a boy or a girl, hiding behind one of the women. I couldn′t really tell. I imagined she was a girl and I couldn′t stop thinking about her: ultimately she would become the narrating voice of ″The Slave Pens″ – ′Atiqa bin Shatwan, the novel′s main protagonist.

I wrote a short story and left it there. I certainly didn′t think I would write a novel. In 2012 I moved to Rome to start my PhD. Initially, I had intended to research the issues associated with learning Arabic as a foreign language, but my real interest was in the history of the slave trade during the Ottoman period.

Fortunately my professor consented to me changing subjects. The research I conducted for my PhD stood me in good stead when it came to writing the novel. By that time I had moved from Rome to Palermo. Unemployed owing to an outstanding residency permit and with time on my hands, I started writing.

I felt lonely and isolated, despite sharing a flat. I kept thinking of ″The Pens″, living with the story and conversing with its characters. When it came to writing certain sections, I would sometimes find myself crying. I spent long hours trying to exorcise the profound influence this book had on my being. During the last year of writing, I put the picture aside and the characters would move in front of my eyes.

As soon as I finished the novel, I sent it to the publisher. I was pleasantly surprised when it was accepted. During that difficult time, it proved the light at the end of the tunnel. Holding the book in my hands, I realized that it wasn′t just mine anymore. It wasn′t just a thought, it was something tangible.

Did you use dialects in the novel?

Binshatwan: I had worked really hard to try and reproduce the slave dialect in the dialogues. Saqi, the publisher, said they loved the novel, but that the dialogues had to be re-written in fusha. However, I did manage to use some dialect relating to clothing, food, place names and – most significantly – traditional slave songs. No one can change a word of them. They are a form of folk poetry and they cannot be transcribed into classical Arabic.

Names and identity are so important in this novel. Why did you chose ′Atiqa for the main protagonist?

Binshatwan: I chose ′Atiqa because it is a name that was given to freed slaves. Though she is no longer a slave, her name reveals something about her past. Society will always look at her as a slave. She will always be regarded as a second-class citizen.

Who is Aunt Sabriyya?

Binshatwan: Aunt Sabriyya′s real name is Ta′weeda. She changes her name when she runs away from a brothel. She hides her real identity from her daughter ′Atiqa, to protect her, fearing that her real family might kill or sell her.

′Atiqa is Muhammad bin Shatwan′s daughter, but he can′t acknowledge her as his daughter because her mother is a slave. He is afraid of his family. Ta′weeda dies as she tries to recover letters proving her daughter′s identity from the burning pens.

There is a character in the novel called Giuseppe. Is he Italian?

Binshatwan: In reality Giuseppe is Yousuf. He is a slave, but the Italian missionaries and the nuns took him in and gave him an identity.

When he returns from Italy, Giuseppe prefers to use his old name for fear that the Libyans will accuse him of having converted to Christianity. But he is still a Muslim. The funny thing is, some people call him Yousuf Giuseppe.

Names are so important in the Libyan culture because they reveal your identity. By calling him Yousuf Giuseppe, they also imply that this man travelled to Italy as a slave and he came back as a free man. The name has always a story. Giuseppe has a pharmacy. ′Atiqa, who later becomes his wife, works at the Italian Hospital with the nuns. I chose these jobs for them as I wanted to find a place where pain was shared and where help is offered to everyone, without discrimination.

′Atiqa and Giuseppe have a boy and a girl, which they call after her parents, although she has only seen her father in pictures. After many generations, these people are called after their forefathers. They are free, but they carry the same names as their slave ancestors. They are proud of their roots. This is in itself a great human value.

Is this story inherently Libyan?

Binshatwan: This is not only a Libyan story, it belongs to humanity. The slave trade was common practice in the Ottoman empire. My book addresses a chapter of history that applies to the whole Arab and Islamic world.

Why did you give your surname to Muhammad?

Binshatwan: I avoided using other family names because I didn′t want to clash with people′s real life sensitivities. So, I used my own.

Did you think you would reach the IPAF shortlist?

Binshatwan: Honestly, it was a complete surprise. When I made it to the longlist, I thought my life had been turned upside down, a radical change. People in Libya were also very happy. It is the first time Libya has reached both the longlist and the shortlist.

Interview conducted by Valentina Viene

© Qantara.de 2017