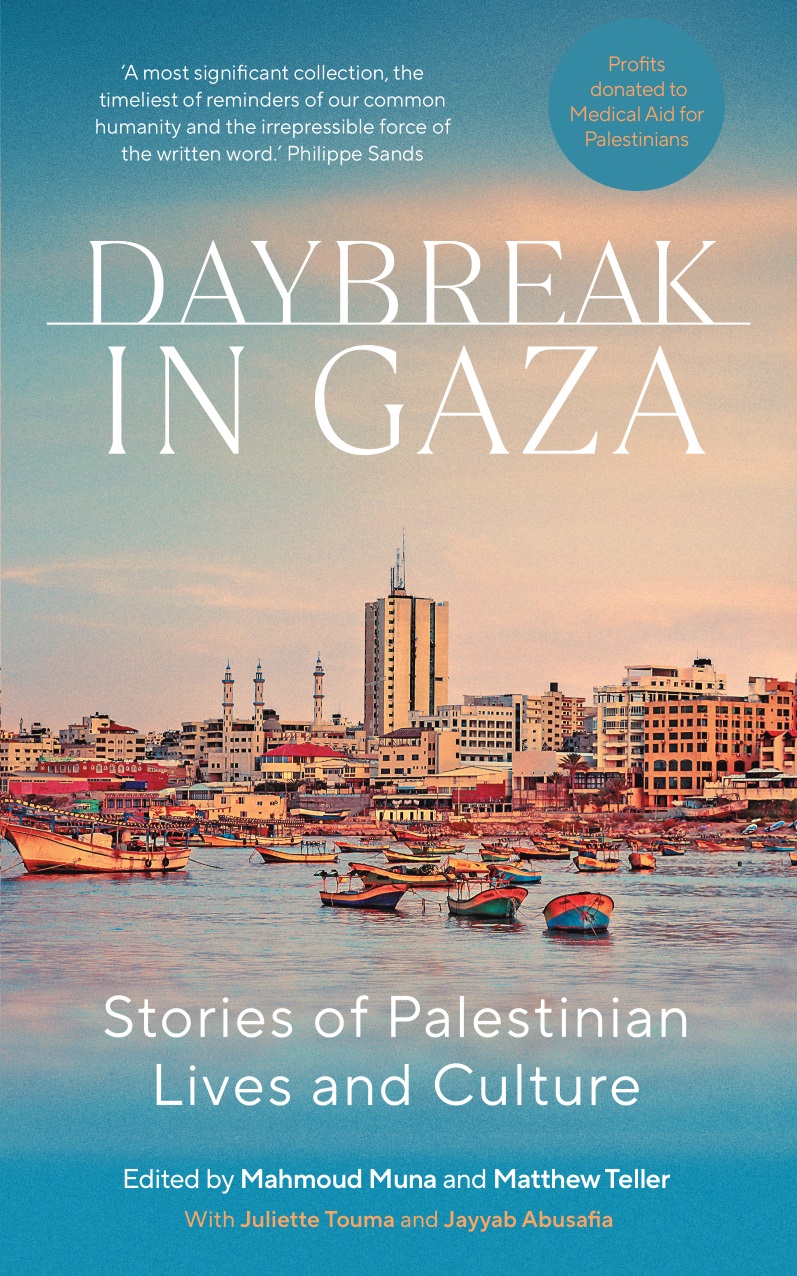

"A book about hope, anger and anguish"

Qantara: Mr. Muna, in the preface to “Daybreak in Gaza” you, together with Matthew Teller, Juliette Touma and Jayyab Abusafia raise the question: “what, specifically, is the role of writers, artists and others engaged in the creative industries as the war in Gaza unfolds?” Have you found an answer yet?

Mahmoud Muna: I think this book is the answer. I am not a doctor, so I can’t go to the hospital and help people survive. I am the owner of a bookstore. When political leaders across the board fail their nations, we—as writers, intellectuals, and those who have a platform—should spread awareness, offer a different narrative, challenge the mainstream and raise controversial issues. This is not just true in the context of Israel and Palestine but everywhere in the world, particularly in times of crisis.

Usually, collecting, editing and printing such a large number of testimonies as presented in “Daybreak in Gaza” takes quite some time. You managed to do so in just a few months. How?

After the war started in October 2023, I would go through the list of names in my notebook and call my friends in Gaza every day to check on them. By December the question “how are you?” became more difficult to ask, and the answers became shorter by the day. I therefore replaced “how are you?” with “tell me more”. I wanted to know about their life, their work, their favourite restaurant or favourite gym before the war. By February and March, my co-editor (the journalist Matthew Teller) and I started to get in touch with people beyond our networks. That’s how we ended up collecting the stories of about 120 people—artists, shop owners, teachers—in short Gazans from many different walks of life. Originally, the book was supposed to be half the length. We had to go back to our publisher, UK-based Saqi Books, three times to request additional pages.

How did you decide which perspectives to include and when to stop collecting them?

We set the deadline for August for several reasons. We wanted the book to be published in October to commemorate the one-year mark of the war, but we were also worried about losing some of the people we interviewed, which, sadly, is what happened. At first, we did as much as we could ourselves. Then we decided to also include excerpts from already published material that didn’t get enough exposure.

The book is published in English and targets an international audience. How would you define its purpose?

This book seeks to humanise the stories of people from Gaza. Our aim is to inform decision-making about the war and hopefully contribute to the pressure for an immediate ceasefire. This is a book that will make people cry as much as it makes people laugh. It is a book about hope as much as it is about anger and anguish. It is a cry for reform and change, and a call to recognise Gazans as normal people. I encourage the readers to reach out to the writers themselves. Most of them are still alive; they have social media accounts. Reach out to them: ask them questions, and send them your comments. Our role as editors is almost finished now that the book is on the shelves. But it would be wonderful to see readers continue the conversation.

Showcasing Palestinian perspectives

Fikra culture magazine publishes literature and art by Palestinians from all over the world. The editors hope it will serve as a platform for the dispersed community to debate and dream – and defend itself against censorship from all sides

Which stories in the collection speak to you the most?

The story that shakes me the most is told through the eyes of child protection officer Hossam al-Madhoun. One excerpt of his war diary talks about a boy on the street who offers to let people look at themselves in a mirror in exchange for one Shekel (€0.25). Apparently, there are not that many intact mirrors left in Gaza at this stage because people are constantly on the move and so many are living in tents. It’s a very powerful story because mirrors are a way of reflecting, of looking at yourself, in a metaphorical sense as readers of the story, and asking: what are we doing? What can we do? What is our stance?

In my opinion, the most beautiful story is the one by Izzeldin Bukhari which takes place before the current war. He writes about trying to transport a cat from Jerusalem to his sister’s wedding in Gaza. To do so, he must go through all kinds of ordeals at the Erez Crossing checkpoint, first facing the Israeli soldiers and then Hamas on the other side of the fence. To me, this story captures the essence of occupation and oppression in every detail of a human being’s life. Every time I travel to Europe, people check in their cats and dogs at the airport, it’s completely normal. But over here taking a pet 90 kilometres across the border is a big deal.

Due to the political circumstances, you have never been to Gaza yourself, so this small, contested piece of land is a place you have only imagined rather than seen firsthand. Was there anything that surprised you while collecting these stories?

My distance from Gaza is a disadvantage, on both the aesthetic and emotional levels. I don’t know what Gaza sounds like. I live in a city on top of a mountain, and I don’t know the meaning of the sea for the people in Gaza. But our other two co-editors filled in the blanks: Juliette Touma is the director of communications for UNRWA and has been to Gaza many times, Jayyab Abusafia is a journalist from Gaza who now lives in London.

What I did underestimate is the diversity of the people in Gaza. I used to think of Gaza’s population as belonging to two main categories: those whose families are originally from Gaza and those whose families fled there as refugees. I knew there were Christians and Muslims but in terms of subcategories—like class, or the fact that there are Gazans with African or Armenian roots—there are many things I was not aware of. I hope this comes as an interesting surprise to the readers, too.

Making the human experience tangible is also the role of journalism. At the beginning of the war, you complained in a piece for the London Review of Books about foreign journalists walking into your store and asking for recommendations but failing to do their job properly. Would you say that more than one year later, the international coverage of the war has improved?

Among the journalists I meet, the conversation has opened up. But I don’t think more than 40,000 Palestinians should have had to be killed for that to happen. The intentions of the Israeli leaders were obvious from the beginning—a very long, bloody war of revenge. In 2024, you would hope that the world would be able to call out crimes and genocide before they happen. Now we are even struggling to call it that, especially in places like Germany.

It also seems that international journalists have accepted that they are not able to be in the field, covering stories from their offices instead and relying on government press briefings. The only way international outlets are granted access is by being embedded with the Israeli army. Yet, this situation seems to have been normalised.

If you allow me to be that international journalist asking for advice on behalf of Qantara’s readers who might not be able to visit your store in East Jerusalem: which books do you recommend to better understand Gaza’s rich history and its people—other than the one you just edited?

I would start with “Lights in Gaza” edited by Jehad Abusalim and Jennifer Bing which beautifully compiles short stories. Then I would recommend “Drinking the Sea in Gaza” by Israeli veteran journalist Amira Hass, which is a classic providing the political background. The works of economist and scholar Sara Roy present a critical analysis of the development work carried out in Gaza in recent years. “Gaza: Preparing for Dawn” by journalist Donald Macintyre is also an important one. For those interested in Hamas, I recommend Tareq Baconi’s recent book, and for the broader history, “Gaza: A History” by Jean-Pierre Filiu is the one to go to.

Daybreak in Gaza: Stories of Palestinian Lives and Culture

Edited by Mahmoud Muna and Matthew Teller with Juliette Touma and Jayyab Abusafia

Saqi Publishing House 2024

336 pages, £14.99

© Qantara.de